Every movie is a story about redemption. Warrior (2011) and Good Will Hunting (1997) are no different, but what they tell us about redemption—and its source—could not be less similar.

Every movie is a story about redemption. Warrior (2011) and Good Will Hunting (1997) are no different, but what they tell us about redemption—and its source—could not be less similar.

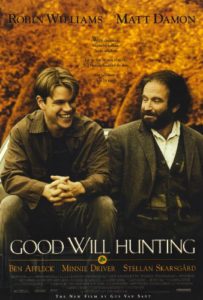

Good Will Hunting is a story about Will Hunting (Matt Damon), a South Boston working-class troublemaker who also happens to be a genius with a photographic memory. While working as a janitor at MIT, Hunting solves a theretofore unsolvable theorem—one that had flummoxed the best and the brightest of the world’s mathematicians. Hunting solves it in a matter of minutes while mopping a floor. Once the professor who posed the problem to his students, Gerald Lambeau—played by Stellan Skarsgard who is brilliant at reminding you of those three professors you had in college who creeped you out a bit because they had spent a little bit too much time surrounded by nothing but co-eds and journal reviews—discovers Hunting, a kid from Southie with no education, had solved his theorem, he immediately tries to enlist Hunting into his world.

Unfortunately, Hunting loves three things a little too much to give Lambeau the time of day: his friends (Ben Affleck, Casey Affleck, and the incomparable Cole Hauser), Southie, and fighting. He particularly loves fighting with his friends in Southie. These actions land him in jail and give Lambeau his opportunity: supervised release for Hunting with the stipulation that he work with Lambeau and see a therapist. For a working-class kid from Boston, jail would probably be preferable.

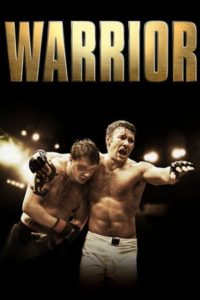

Like Good Will Hunting, Warrior centers around a working-class kid who is gifted with an incredible talent. In this case, however, Tommy Riordan (Tom Hardy) isn’t much of a thinker, but he is one of the best wrestlers and MMA fighters in the world—an ex-Marine who went undefeated in wrestling in high school and, earlier on in the film, takes out a famous UFC  fighter in less than 10 seconds. The movie sets the table brilliantly in the opening scene. Tommy comes back home, unexpectedly (and drunk), to his father, Paddy Conlon (Nick Nolte). It becomes clear that Paddy was an abusive alcoholic during Tommy’s childhood which eventually drove Tommy and his mother to flee the abuse. Tommy’s brother, Brendan Conlon (Joel Edgerton), however, stayed, where he married his high-school sweetheart, had two beautiful children, and got a job as a schoolteacher.

fighter in less than 10 seconds. The movie sets the table brilliantly in the opening scene. Tommy comes back home, unexpectedly (and drunk), to his father, Paddy Conlon (Nick Nolte). It becomes clear that Paddy was an abusive alcoholic during Tommy’s childhood which eventually drove Tommy and his mother to flee the abuse. Tommy’s brother, Brendan Conlon (Joel Edgerton), however, stayed, where he married his high-school sweetheart, had two beautiful children, and got a job as a schoolteacher.

The reasons for Tommy’s return are less clear. His bitterness, nay, rage at his father for the abuse and his brother for staying while he fled with his mother, are, however, quite clear. Paddy makes it clear to Tommy that he has managed to get (and stay) sober and has returned to his Catholic faith. This only serves to make Tommy angrier as he recounts his pious, faith-filled mother’s slow decay and premature death. “Your Jesus wasn’t there; I guess he was down at the bar, forgiving all the drunks.” Paddy had renounced the bottle and found a Savior. For a bitter kid clinging to his hate, an abusive alcoholic would probably be preferable.

“Family likeness has often a deep sadness in it. Nature, that great tragic dramatist, knits us together by bone and muscle, and divides us by the subtler web of our brains; blends yearning and repulsion; and ties us by our heart-strings to the beings that jar us at every movement.”

—George Eliot

One of the most enduring themes of the human condition is that so much of our brokenness is caused by our family and upbringing. Rare is the case in which a broken and tortured adult looks back fondly at their childhood and wonders where it all went wrong. Instead, the dysfunction of our childhood is so often that from which we seek redemption.

One of the most enduring themes of the human condition is that so much of our brokenness is caused by our family and upbringing. Rare is the case in which a broken and tortured adult looks back fondly at their childhood and wonders where it all went wrong. Instead, the dysfunction of our childhood is so often that from which we seek redemption.

Both films portray this truth unflinchingly, but from completely opposite angles. In Good Will Hunting, the issue is the absence of family. Hunting grew up an orphan in various foster homes. What takes most films thirty minutes of table-setting was accomplishedin a single, devastating three-minute interaction between Hunting and his girlfriend, Skylar (Minnie Driver). Hunting concedes that he’s been lying to Skylar during their entire relationship by claiming he had multiple brothers and a loving family and culminates in one of Damon’s best-delivered lines:

“You don’t wanna hear that I got f***ing cigarettes put out on me as a little kid, that this isn’t f***ing surgery, the motherf***er stabbed me!”

In Warrior, however, the issue is the opposite. The rejoinder to Hunting’s assumption that it was the absence of family that caused his struggle is found in Tommy, who serves as a clear distillation of the fact that merely having a family is insufficient. The “subtler web of our brains”—the dark recesses of the mind where dragons and addictions and ghouls and hate all coexist—can lead a family, with all of its “yearning and repulsion,” to a devastation that would perhaps make mere absence preferable. The popular notion that it is better to feel pain than nothing at all surely was coined by someone unfamiliar with real pain. The family dysfunction and brokenness in Warrioris perhaps best summed up by something Tommy tells his father late in the film: “The only thing Brendan and I have in common is that we both have absolutely no use for you.” He doubles down later when he tells Brendan “you ain’t my brother. My brothers were in the Corps.”

In Warrior, however, the issue is the opposite. The rejoinder to Hunting’s assumption that it was the absence of family that caused his struggle is found in Tommy, who serves as a clear distillation of the fact that merely having a family is insufficient. The “subtler web of our brains”—the dark recesses of the mind where dragons and addictions and ghouls and hate all coexist—can lead a family, with all of its “yearning and repulsion,” to a devastation that would perhaps make mere absence preferable. The popular notion that it is better to feel pain than nothing at all surely was coined by someone unfamiliar with real pain. The family dysfunction and brokenness in Warrioris perhaps best summed up by something Tommy tells his father late in the film: “The only thing Brendan and I have in common is that we both have absolutely no use for you.” He doubles down later when he tells Brendan “you ain’t my brother. My brothers were in the Corps.”

Brokenness often leads to anger. The only question is: what is the object of this anger? Will Hunting was angry at his upbringing, at authority, and at the world. Tommy, though, was angry at God, at the notion that Jesus forgives drunks, but didn’t save his mother. The tragedy of brokenness and dysfunction is not found in the brokenness per se, but when we turn against the one who can put the pieces back together. A critical analysis of the two films raises a question: which is better, to be angry about God or to ignore him altogether?

In the show Mad Men, a young, aspiring advertiser tells Don Draper “I feel sorry for you.” Draper responds, calmly: “I don’t think about you at all.” In another scene, a young advertiser angrily tells Don “You never said ‘thank you’!” Draper responds by screaming “That’s what the money is for!” Is it better to be angry at God or ambivalent towards him? Although we often think those who are angry at God are furthest from Him, I think the answer is found in which of the two relationships in Mad Menended in reconciliation.

In the show Mad Men, a young, aspiring advertiser tells Don Draper “I feel sorry for you.” Draper responds, calmly: “I don’t think about you at all.” In another scene, a young advertiser angrily tells Don “You never said ‘thank you’!” Draper responds by screaming “That’s what the money is for!” Is it better to be angry at God or ambivalent towards him? Although we often think those who are angry at God are furthest from Him, I think the answer is found in which of the two relationships in Mad Menended in reconciliation.

The process of redemption in these films required the use of a father figure—an older brother in Warrior, a therapist (Robin Williams) in Good Will Hunting. In both cases, Will and Tommy initially rejected the figurative process of redemption by quite literally rejecting Sean and Brendan.

Sean and Brendan, however, convey opposing messages. Sean seeks to help Will see that the solution to his problems was acceptance; Brendan sought to help Tommy understand that the solution to his problems was to change. Sean sought to help Will understand that “it’s not your fault.” Brendan sought to help Tommy forgive and to reconcile. In both cases the process of redemption culminates in surrender. Will surrenders to the fact that it’s not his fault; Tommy taps out. Will goes to see about a girl; Tommy leans on his brother, the one not in the Corps.

There are many stories of redemption, and there is one story of redemption. The limitation of both Good Will Hunting and Warrior is not that they went too far back, by placing the source of the brokenness at a dysfunctional upbringing. The limitation is that they did not go back far enough. We are not the source of our brokenness, but neither is our family, or our upbringing, or our genetics, or our demons. The source of our brokenness is a paradise lost, a serpent slithering away into a sunset, an apple behind him, along with a vision of the generations of brokenness to come.

There are many stories of redemption, and there is one story of redemption. The limitation of both Good Will Hunting and Warrior is not that they went too far back, by placing the source of the brokenness at a dysfunctional upbringing. The limitation is that they did not go back far enough. We are not the source of our brokenness, but neither is our family, or our upbringing, or our genetics, or our demons. The source of our brokenness is a paradise lost, a serpent slithering away into a sunset, an apple behind him, along with a vision of the generations of brokenness to come.

The true story of redemption is a story of paradise found. It is also a story about surrender. Not to the notion that “it’s not our fault” or even to the notion that it is. It isabout a surrender to the plan of redemption, where a God would become a baby, die on a tree, rise from a tomb, fly into the heavens, and come back on a horse, wielding a sword that will end our brokenness and dysfunction—with all the addictions and cigarette burns that come with it. It is a story of the original prophecy: the slithering serpent crushed by a God-man, the one on whom the edifice is built, the one who, in his infinite mercy, is still down at the bar, forgiving all the drunks.

Jacob Phillips is a consumer protection attorney in Orlando, Florida and a film buff who considers 1970s cinema to be the pinnacle of Western Civilization. He has written for The Gospel Coalition, Morning by Morning, and blogs regularly for his church’s blog, Redeemer Church in Lake Nona. He is married to Sarah, an elementary schoolteacher, and has a one-year-old son, Miles Jameson, named (unbeknownst to Sarah) after Jake’s favorite poem and favorite whiskey.