“Who killed the world?”

“Who killed the world?”

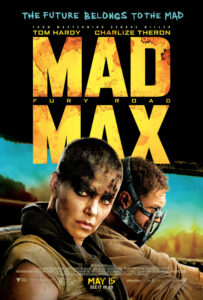

This question haunts the now five-year-old masterpiece Mad Max: Fury Road. Though it is only uttered twice in the film, the state of Fury Road’s world demands it be asked. The barren desert landscape bears witness to the pretense at the heart of humanity’s boast of progress. “Mankind has gone rogue, terrorizing itself,” a voice in the opening sequence pronounces. The environmental disasters and catastrophic warfare that brought the world to this point were only made possible by the advances we pride ourselves over now.

The desolate future envisioned in the Mad Max films lays bare the emptiness which always threatens our efforts to build something meaningful. We fear the atavistic impulse that would revert us to fighting like rats over the scraps left by the detonation of civilization for at least two reasons. First, we shudder when we recognize the likelihood that we ourselves would succumb to the savagery of the war of all against all. But second, we fear we wouldn’t be strong enough to defend ourselves from the monsters.

There’s a phrase attributed to Antonio Gramsci: “The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters.” Slavoj Zizek seems to have popularized this rendering of Gramsci’s apothegm1 but what Gramsci wrote in his prison notebook was, “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.”

But perhaps we don’t have to choose between two different meanings in these renderings.

Don’t monsters arise out of the painful fractures pocking our world? Out of the death throes of the present order? They seem to arise in every effort humans make to bring about something new. But these efforts always carry the taint of the old era, carry forward the sickness that infects and undermines our best ambitions. The risk of such action is becoming a monster.

In the distressingly near future universe of Mad Max, monsters emerge out of the void following the collapse of technological modernity. Morbid symptoms were already showing themselves in the decline of the old world, producing monsters who would draw followers on the premise of fighting against those very symptoms. But they never do. Such monsters always trade in our fears of defilement to draw us into defilement in their campaigns to rid the world of the infection that brings our efforts to ruin.

The Mad Max films present us with the end of a certain order and in so doing depicts the end, the outcome, of that order. Liberal democracy was supposed to be the end of history— what comes after its end? Fury Road depicts one potential future, and we would be wise in our current moment to heed the parallels between the future and our present.

Totalitarianism is always more than a political arrangement—it’s a religious phenomenon, commandeering the human instinct to give away our allegiance and our worship. This basic drive in human beings is exploited in totalitarian regimes to create twisted parodies of the eschatological kingdom and make war against the present.

It doesn’t take a religious believer to recognize this. In his analysis of Enlightenment morality, Theodor Adorno quotes a character from a story by the Marquis de Sade: “Take its god from the people that you wish to subjugate, and then demoralize it; so long as it worships no other god than you, and has no other morals than your morals, you will always be its master.”2 The despots who rule us enfeeble us with hopelessness, with misinformation, with expedient disasters, and when we’ve been broken down sufficiently, steal our worship. Having perceived the moribundity of our world these monsters emerge from the shadows to finish it off.

The Mad Max series made possible the tradition of the charismatic tyrant without which there is no Duke of New York, no Governor or Negan, none of the larger-than-life post-punk demigods of dystopia we have come to love. But these demigods among the post-liberal ruins have proven to be glimpses of the demagogues that were to come, that have arrived in our present.

The Mad Max series made possible the tradition of the charismatic tyrant without which there is no Duke of New York, no Governor or Negan, none of the larger-than-life post-punk demigods of dystopia we have come to love. But these demigods among the post-liberal ruins have proven to be glimpses of the demagogues that were to come, that have arrived in our present.

Fury Road’s tyrant is Immortan Joe, a survivor of the old world who has installed himself as the god-dictator of one community in the Wasteland. He rules from an impregnable stronghold of rock towers he has styled the Citadel, his regime enforced by his fanatical War Boys and his total monopoly on fresh water which he doles out to the Wretched— the homeless, disease-stricken, and disabled masses who flock to the Citadel for “survival.”

They are the base Immortan Joe exploits to replenish his ranks: the fittest of their children are taken and indoctrinated into the Cult of V8 to serve as soldiers absolutely loyal to Joe. His domination is total; if he withholds the resources he meagerly offers, the Wretched perish. “I am your redeemer!” he bellows to them as he releases a torrent of water to be snatched up and fought over. “It is by my hand you will rise from the ashes of this world!” Joe has erected an entirely new social imaginary, the purposes, language, and rituals of which are formed entirely around his death cult. The complete and utter demoralization he subjects them to deepens their enslavement, closes off any possibility of something different. Something better.

Enter Max Rockatansky, apocalyptic drifter, dehumanized bearer of a vocation he never chose for himself.

Throughout his film series, Max has lost everything. This isn’t unique to him, however. “As the world fell,” Max narrates at the beginning of Fury Road, “each of us in our own way was broken.” Every person he’s encountered from The Road Warrior on has suffered the total upheaval of their lives in the old world. He is the one who runs from the living and the dead: always fleeing the neo-barbarians that have claimed the Wasteland for themselves and the memories of those he couldn’t protect. He purposelessly makes his way through the wastes, surviving, unattached to any place or to any community.

“Do you think you’re the only one that’s suffered?” the leader of one community rebuked him in The Road Warrior. “We’ve all been through it in here. But we haven’t given up. We’re still human beings with dignity. But you? You’re out there with the garbage. You’re nothing.” A maggot living off the corpse of the old world.

Max had already feared such an outcome before society completely collapsed. Already he was scared of becoming what he was fighting, “a terminal psychotic, except that I’ve got this bronze badge that says I’m one of the good guys.” But following the loss of his family and the vengeance he exacted he was left without even that bare signifier, reduced to a shell of a man little different from the scavengers he outruns each day.

Max, however, has surprised everyone, including himself, by rising to the occasion to take up the mantle of reluctant deliverer times before. In Fury Road, however, he’s lost even the gains in humanity he’s made in previous films. Max has never been very eloquent, but when we meet him at the beginning of Fury Road he has been reduced to animalistic survival. He hasn’t heard the sound of his own voice for who knows how long— only the voices of the people he promised to help but couldn’t save.

Max, however, has surprised everyone, including himself, by rising to the occasion to take up the mantle of reluctant deliverer times before. In Fury Road, however, he’s lost even the gains in humanity he’s made in previous films. Max has never been very eloquent, but when we meet him at the beginning of Fury Road he has been reduced to animalistic survival. He hasn’t heard the sound of his own voice for who knows how long— only the voices of the people he promised to help but couldn’t save.

Max’s arrival into Immortan Joe’s dominion isn’t the intentional effort of a liberator; he’s taken captive by a band of War Boys and brought to the Citadel to serve as a blood bag— a living transfusion for Joe’s cancerous soldiers. Nor is it his intention to cross paths with Furiosa, Joe’s ablest lieutenant, who has fled the Citadel with Joe’s “breeders”— the wives he’s forcibly taken to produce able-bodied heirs. Nor does he choose to be chained to Nux, one of Joe’s War Boys whose ambition is to earn Joe’s approval by returning Joe’s wives himself. Several lines of dehumanized powerlessness accidentally converge when Max finds himself aboard the War Rig, along for the ride to find the home Furiosa was taken from: a “Green Place” where Joe can’t harm them.

But the terrible reveal upon which Fury Road turns is the disappearance of that Green Place. Its survivors explain that the soil and the water went sour, and another gang claimed it for themselves. The ideal home totally removed from the world’s furor and scarcity doesn’t exist. Furiosa is devastated. All her hopes of redemption hung entirely upon returning there.

“Hope is a mistake,” Max cautions Furiosa when she offers Max a place among the escaping women, determined now to drive across the desert in search of another safe place. Like the fantasy of returning to a better time (a “greater” time?), the delusional consolation of such a place in this world is no hope at all— it’s an enticement to despair and death. Max elects to stay behind as he has other times in the past.

In a moment symmetrical to the film’s first glimpse of Max he stands overlooking a sea of sand. This time, however, he isn’t trembling with the anguished burden of his trauma. He’s seen a different way out of the nightmare. He races to reconvene with Furiosa and her band to propose an alternative. Abandon the false hope of an Eden somewhere out there and find their way home back where they began. The hard way back the way they came, running from the monsters, back to the Citadel.

Max has recognized they can never run far enough to rid themselves of the wreckage of the past. None of us can outrun what haunts us: we can only charge straight into it, face its fury, and fight our way home. This is the way that fulfills the needs of every member of this disparate group: Furiosa’s need to expiate her sins as an instrument of Immortan Joe’s regime; the wives’ need for a habitable home for their children; the Green Place survivors’ need to continue their ecological stewardship. Nux, having passed through the dark night of disenchantment with the uncaring Immortan, finds his old mission repurposed: he will return the wives to their home after all. And Max will take the risk of identifying himself once more with the vulnerable, to be what they need him to be.

Max has recognized they can never run far enough to rid themselves of the wreckage of the past. None of us can outrun what haunts us: we can only charge straight into it, face its fury, and fight our way home. This is the way that fulfills the needs of every member of this disparate group: Furiosa’s need to expiate her sins as an instrument of Immortan Joe’s regime; the wives’ need for a habitable home for their children; the Green Place survivors’ need to continue their ecological stewardship. Nux, having passed through the dark night of disenchantment with the uncaring Immortan, finds his old mission repurposed: he will return the wives to their home after all. And Max will take the risk of identifying himself once more with the vulnerable, to be what they need him to be.

Fleeing across endless desert is madness. But this? “Feels like hope,” Nux, the War Boy reborn with Max’s blood, remarks. Not escape, but starting again. It will be hard, Max promises, “but at least that way we might be able to— together— come across some kind of redemption.” Bolstered by substantive hope, the group fights a brutal battle back to a mountain pass where they trap Joe’s and his allies’ war parties. This is the narrow way that leads to life, to a Citadel where there is more than enough water to shower all: a great, heterogeneous throng of newly free men, women, and children hail Furiosa as dragonslayer and are purified in the water Joe has hoarded as a weapon.

The entire Mad Max franchise depicts Max’s reluctant responses to the monsters of the in-between. Max continually finds his heroism and nobility wrenched out of him when others need him, their desperation piercing through the thick knots of his own self-loathing and shame to release the good man he’s wanted to be. What we have been, what we have done, doesn’t have to determine our destiny. The accusing voices of all that has gone so terribly wrong don’t have to debilitate us the rest of our lives. We can act now. Act on the principles that animated us before the trauma came, before we became accustomed to compromise, to survival or protecting old privileges.

None of us reconcile ourselves to our failures or find healing for our triggers in isolation. In community our trauma can be repurposed, can spur us on back into the darkness we wish we could hide from but cannot. Alone, we break, and ununified, our world crumbles. “We must learn to live together as brothers or perish together as fools,” Martin Luther King, Jr. said. The options are never individualistic. We are always already bound together for good or ill.

None of us reconcile ourselves to our failures or find healing for our triggers in isolation. In community our trauma can be repurposed, can spur us on back into the darkness we wish we could hide from but cannot. Alone, we break, and ununified, our world crumbles. “We must learn to live together as brothers or perish together as fools,” Martin Luther King, Jr. said. The options are never individualistic. We are always already bound together for good or ill.

Max’s task before the world went to hell was the same as ours is now: keep chaos at bay. Preserve decency. Resist the pull towards brutality a savage world exerts upon us. Own the sins of the past. And diligently guard against the monsters ever seeking a foothold. But we won’t be able to do this if our senses are dulled by the benefits of the status quo, or if we tenaciously cling to conspiracy theories that assure us everything actually is all right, or if we stay in lockstep with our memetic tribe and spurn the needs of others who are not like us. Many of us seek redemption for the sins we fear have claimed our existence, but we must reject all self-styled saviors offering this-worldly “redemption.” None of them can effect this. None of them want to. They only want your worship.

The monsters that materialize out of the morbid symptoms of technological modernity build their empires from the ruins of these divisions. They depend upon our stubborn refusal to come together over common goods, on our naive need to give the benefit of the doubt to loathsome, power-hungry men. Immortan Joe doesn’t represent the quotient of depravity latent in every single human being— he is the potential our race occasionally actualizes, our own death drive enfleshed and eager to force us to our knees. He is the monster we allow to go unchallenged for too long in our hope he will change his ways.

That hope is a mistake.

The reductionistic, Lockean contractualism of radically separate individuals enshrined in our American inheritance won’t suffice to see us through the crisis of our era because it facilitated and propelled that crisis in the first place. And the factions we look to for the safety of belonging won’t steer our world away from the brink— they will only make us plummet all the more swiftly.

Who killed the world? Someone alive now will have pushed the button, but all of us will have to answer for how they got to that button. Perhaps you or I aren’t the monster Gramsci warned us about but if we seek the luxury of withdrawal from struggle, if we are too civil and admit certain people into positions of power, if we set off on a daft campaign to return to an idyllic golden age that never existed, we enable those monsters. “If you can’t fix what’s broken, you’ll go insane,” Max warned. Now is the time to face the specters of our past and refuse the future our present is sclerotically hardening into before it is too late.

• • •

1 But it doesn’t appear to have originated with him— it’s possible he worked from a text of Gustave Massiah, who translates Gramsci into French. There the phrase becomes something like, “The old world is dying, the new world is slow to appear and in this chiaroscuro appear monsters.”

2 Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments, trans. John Cumming (New York: Seabury Press, 1972), 89.