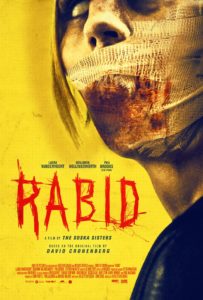

In the history of cinema, several filmmakers have stuck out as memorable, those who left a mark on the industry and have, in some way, influenced generations of filmmakers after them. In the world of horror cinema, in particular, one of the many greats which stands out is the legendary Canadian director David Cronenberg, the father of body horror. Many of his films, such as Videodrome and eXistenZ, are considered by many to be modern horror classics. Like any legendary filmmaker, it is a bold move for any filmmaker to try and remake one of these films. And yet, fellow Canadians Jen and Sylvia Soska (aka The Soska Sisters) did just that with another classic Cronenberg film, Rabid. The original film tells the story of Rose, who is injured in a motorcycle accident along with her boyfriend Hart Read and is taken to a plastic surgery clinic run by Dr. Dan Keloid. Through an experimental reconstructive procedure, Rose develops an insatiable appetite for blood, which she satiates through a projectile which comes out from under her arm, and releasing an extremely aggressive form of rabies to the masses. The Soska Sisters’ remake, while keeping Rose as a motorcycle accident victim, has much more of a developed backstory and context to her character than Marilyn Chamber’s original Rose had.

In the history of cinema, several filmmakers have stuck out as memorable, those who left a mark on the industry and have, in some way, influenced generations of filmmakers after them. In the world of horror cinema, in particular, one of the many greats which stands out is the legendary Canadian director David Cronenberg, the father of body horror. Many of his films, such as Videodrome and eXistenZ, are considered by many to be modern horror classics. Like any legendary filmmaker, it is a bold move for any filmmaker to try and remake one of these films. And yet, fellow Canadians Jen and Sylvia Soska (aka The Soska Sisters) did just that with another classic Cronenberg film, Rabid. The original film tells the story of Rose, who is injured in a motorcycle accident along with her boyfriend Hart Read and is taken to a plastic surgery clinic run by Dr. Dan Keloid. Through an experimental reconstructive procedure, Rose develops an insatiable appetite for blood, which she satiates through a projectile which comes out from under her arm, and releasing an extremely aggressive form of rabies to the masses. The Soska Sisters’ remake, while keeping Rose as a motorcycle accident victim, has much more of a developed backstory and context to her character than Marilyn Chamber’s original Rose had.  Rose in the remake is a fashion designer trying to get her big break in the industry under the brutally critical eye of Gunter. After her accident, her stem cell manipulation procedure at the Burroughs Clinic (a research center led by Dr. William Burroughs) looks to have provided a slow return to normalcy, as her face and body slowly recover from both the accident and the surgical procedure. However, like Cronenberg’s original film, the side effects of this procedure kick in, unleashing a taste for blood and the increasing body count of this new strain of rabies.

Rose in the remake is a fashion designer trying to get her big break in the industry under the brutally critical eye of Gunter. After her accident, her stem cell manipulation procedure at the Burroughs Clinic (a research center led by Dr. William Burroughs) looks to have provided a slow return to normalcy, as her face and body slowly recover from both the accident and the surgical procedure. However, like Cronenberg’s original film, the side effects of this procedure kick in, unleashing a taste for blood and the increasing body count of this new strain of rabies.

While the original Rabid seemed to invite conversations around the theme of female sexuality and unchecked passions, this 2019 remake explores themes of personhood and what it means to be human. And while this remake is unfortunately nothing special, even somewhat lackluster, it does a sufficient job of inviting us to consider our own humanity. As Rose’ co-worker Brad says to her as they hang out in a nightclub together, “True beauty lies within the things we have yet to uncover,” which becomes a guiding principle or thematic foundation by which to see the rest of the film. In the Soska Sister’s vision, we are invited to the nightmare where our pursuit of transcending our human limitations turns us into monsters. The clearest evidence of this in the film is Dr. Burroughs himself, who has no moral compass to halt this new vision of humanity he wants to bring to the world. Rose herself is taken aback by this, telling the doctor, “You have no right to play God.” His response says it all: “What God? We are God.” We get a glimpse of the Burroughs Clinic’s sinister intentions even earlier in the film when Rose sees an ad for the clinic on the television, which begins with the words, “Transhumanism: the belief or theory that the human race can evolve beyond its current physical and mental limitations, especially by means of science and technology.” This cult of progress, so to speak, is seen even in the clinic’s medical attire, which look more like the Knights Templar than they do medical professionals.

While the original Rabid seemed to invite conversations around the theme of female sexuality and unchecked passions, this 2019 remake explores themes of personhood and what it means to be human. And while this remake is unfortunately nothing special, even somewhat lackluster, it does a sufficient job of inviting us to consider our own humanity. As Rose’ co-worker Brad says to her as they hang out in a nightclub together, “True beauty lies within the things we have yet to uncover,” which becomes a guiding principle or thematic foundation by which to see the rest of the film. In the Soska Sister’s vision, we are invited to the nightmare where our pursuit of transcending our human limitations turns us into monsters. The clearest evidence of this in the film is Dr. Burroughs himself, who has no moral compass to halt this new vision of humanity he wants to bring to the world. Rose herself is taken aback by this, telling the doctor, “You have no right to play God.” His response says it all: “What God? We are God.” We get a glimpse of the Burroughs Clinic’s sinister intentions even earlier in the film when Rose sees an ad for the clinic on the television, which begins with the words, “Transhumanism: the belief or theory that the human race can evolve beyond its current physical and mental limitations, especially by means of science and technology.” This cult of progress, so to speak, is seen even in the clinic’s medical attire, which look more like the Knights Templar than they do medical professionals.

It is this vision which makes the Soska Sisters’ Rabid a more sinister take on Cronenberg’s classic. As Ernest Mathijs notes concerning the original film in his book The Cinema of David Cronenberg,

[Even] though the infection and the infected rabids desire uncontrolled, messy surroundings, they can really only survive in secluded conditions; once they hit the streets they are not as tough as they thought they were. Metaphorically speaking, real life culture, hardened by centuries of survival, is too strong to be toppled by a few bites and foams, and whenever it feels threatened it bites back, with a vengeance. In that sense, Rabid appeals to Nietzschean philosophies of survival and evolution. But the real reason why the revolution in Rabid fails is what Rose symbolizes. Her actions resemble what Girard calls the scapegoat model. She is maléfique (bad) because she has caused the outbreak…but she is also bénéfique (good) because her actions unite the rest of the population in an effort to set their differences aside and cast out the evil threatening their cultural order…On top of that, Rose’s guilt and self-sacrifice makes her a martyr. By offering herself for the greater good she demonstrates moral concern.

However, while this reading may have worked for the original film, Jen and Sylvia Soska turn Rose’s so-called martyrdom into futility. While she returns to the clinic after a return to normalcy proved to fail, her self-imposed death with a blade across the throat did not stop the monster. In fact, the ending of the film sees Dr. Burroughs apparently using stem cell manipulation again to save Rose’s life, making her “essentially immortal” and her body now subjected to being a vessel for this new human vision. The ending is not hopeful and leaves you feeling as if nothing can prevent you from escaping this so-called progress.

However, while this reading may have worked for the original film, Jen and Sylvia Soska turn Rose’s so-called martyrdom into futility. While she returns to the clinic after a return to normalcy proved to fail, her self-imposed death with a blade across the throat did not stop the monster. In fact, the ending of the film sees Dr. Burroughs apparently using stem cell manipulation again to save Rose’s life, making her “essentially immortal” and her body now subjected to being a vessel for this new human vision. The ending is not hopeful and leaves you feeling as if nothing can prevent you from escaping this so-called progress.

While the film may not make any best horror films of the year lists, it does remind us that perhaps the scariest monster of all is humanity. Like the serpent leading Adam and Eve to their downfall, abdicating their habitation in an Edenic landscape, we lust after forbidden knowledge and the breaking free from out limitations. We don’t want constraints, limitations, and perhaps most of all, we don’t want to face up to our own mortality. Even when tragedy strikes, like a motorcycle accident, we like to think we don’t have to settle for a new normal, that things can go back to the way they were. And yet, this disease—this rabies, if you will—only prolongs the ultimate unveiling of the truth: that to live this way is to not be liberated and set free, but to be in bondage to the monsters all around us and, most importantly of all, in us.