We tend to associate Disney with family-friendly, kid-centric, animated films, replete with hip (On fleek is, perhaps, the more hip turn of phrase, but I do not know.) cultural references, ample humor, and an unshakable—if naive, or misguided—sense of optimism; in some respect, that reputation is well-earned. Disney—both the man himself, and his company—did make animation a viable, profitable art form, after all—a medium of storytelling that has flourished for almost a hundred years now. Whether or not the House of Mouse wholesale deserves this aforementioned equation with lightheartedness or, as some would suggest, childishness, is a topic for a different day. Nevertheless, such blanket statements about Walt or his heirs, while often containing varying degrees of accuracy and truth, are unhelpful insofar as they minimize any potential exceptions to the rule, making it difficult for us to consider the times Disney has gone down the proverbial rabbit hole (or at least stood on the edge of the yawning chasm and contemplated a jump), toward a darker, less elysian destination.

We tend to associate Disney with family-friendly, kid-centric, animated films, replete with hip (On fleek is, perhaps, the more hip turn of phrase, but I do not know.) cultural references, ample humor, and an unshakable—if naive, or misguided—sense of optimism; in some respect, that reputation is well-earned. Disney—both the man himself, and his company—did make animation a viable, profitable art form, after all—a medium of storytelling that has flourished for almost a hundred years now. Whether or not the House of Mouse wholesale deserves this aforementioned equation with lightheartedness or, as some would suggest, childishness, is a topic for a different day. Nevertheless, such blanket statements about Walt or his heirs, while often containing varying degrees of accuracy and truth, are unhelpful insofar as they minimize any potential exceptions to the rule, making it difficult for us to consider the times Disney has gone down the proverbial rabbit hole (or at least stood on the edge of the yawning chasm and contemplated a jump), toward a darker, less elysian destination.

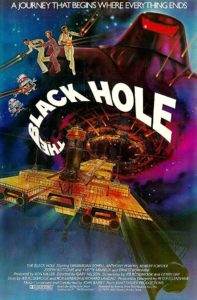

In 1979, Walt Disney Productions released The Black Hole, a big-budget, feature-length, live-action sci-fi film. Set in the year 2130, The Black Hole centers around the crew of a spaceship, who stumble upon a hulking, ostensibly abandoned vessel located on the precipice of a black hole. The crew learn that the ship was part of a mission that was failed and aborted, and so they set off to further investigate. Once onboard, however, they discover that far from being abandoned, the spacecraft is being piloted by the the long-lost Dr. Reinhardt (Maximillian Schell) and scores of his robot workers. Reinhardt has become obsessed with the idea of entering into the black hole in order to uncover the hidden secrets of our existence, but the crew must escape before he steers them into oblivion.

The Black Hole very clearly owes a debt of gratitude to a number of science fiction films of the sixties and seventies—most notably, George Lucas’s Star Wars. In fact, perhaps the only thing keeping The Black Hole from slipping into complete anonymity is its nomination for Best Visual Effects at the 1980 Academy Awards, and assuredly Disney’s technological prowess in this film—much less the budget to make a space film of this magnitude—would not be possible apart from the pioneering work of Lucas and ILM two years earlier. It’s no surprise, therefore, that the futuristic world depicted The Black Hole bears more than a passing similarity to the galaxy far, far away. Disney’s film features blasters that fire red beams, a robot with a British accent and a chirpy attitude, and spaceships so large they look like they could destroy an entire planet. Additionally, The Black Hole dares to meddle with philosophical and religious themes and questions in a way vaguely reminiscent of Tarkovksy’s Solaris (1972) or Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), albeit in a more readily accessible manner than any work by these auteurs. These varied inspirations make the film a truly unique entry in Disney’s filmography.

At is heart, however, beneath its shiny and then-cutting-edge technologically innovative sheen, The Black Hole is on old story—a David and Goliath story. And in true Disney fashion, the film is not content to let its biblical motifs serve as subtext. Everything is laid bare as the crew meet Dr. Reinhardt for the first time about his ship, the Cygnus, where our protagonists’ wide-eyed robot companion, V.I.N.C.E.N.T. (voiced by Roddy McDowall) meets his taller, militarized Cygnus counterpart, Maximillian (voiced by Tommy McLoughlin). The taller robot stares at V.I.N.C.E.N.T., mocking and making threatening gestures, and Reinhardt speaks, ushering in the film’s dramatic conflict. “It’s like David and Goliath,” he says of the two robots, “only this time, David is outmatched.”

The remainder of the film sees the biblical narrative play out on multiple levels, for while Reinhardt explicitly talks of a David and Goliath conflict with respect to the two robots, he implicitly draws the entire crew into this epic battle, casting himself as Goliath, and Captain Holland (Robert Forster), Alex (Anthony Perkins), Pizer (Joseph Bottoms), Booth (Earnest Borgnine), and McCrae (Yvette Mimiex) and David figures. Like their biblical counterpart, the crew is ostensibly overmatched by Dr. Reinhardt and his robot army. Moreover, this David and Goliath story bears out in that Reinhard’s ship is much larger than that of the crew, as it literally envelops and houses their vessel, making their escape all the more improbable. And finally, this Old Testament imagery plays out on a cosmic scale, with Dr. Reinhardt determined to take on a black hole, in all its destructive force and magnitude.

The outcome of these conflicts holds few surprises for those familiar with biblical account. V.I.N.C.E.N.T. is able to defeat his menacing counterpart; Dr. Reinhardt is killed (Parallels only go so far, of course.); and in a bizarre turn of events, the crew are able to defeat the black hole. Unable to escape the gravitational pull of the black hole, the crew instead head straight into it, initiating a five-minute, virtually dialogue-free dream sequence that brings the film to its conclusion.

This final scene is by far the most formally innovative portion of the film. The crew members hear disembodied voices, which are uttering lines spoken  earlier in the film, and they see (or dream, or experience, or travel to an alternate dimension, or something else entirely) Dr. Reinhardt and the evil robot Max merge together into the same being (again solidifying the Reinhardt/Goliath connection). Next, Dr. Reinhardt stands in a Dantesque Hell, a cavernous, rocky place, filled with flames, in which scores and scores of automaton robots march aimlessly. Subsequently and without warning, a door shining full of ethereal light is superimposed onto this hellish landscape; a floating human figure enters therein, and our crew emerges victorious from the black hole and sails toward a brightly shining planet as the screen fades and the credits roll.

earlier in the film, and they see (or dream, or experience, or travel to an alternate dimension, or something else entirely) Dr. Reinhardt and the evil robot Max merge together into the same being (again solidifying the Reinhardt/Goliath connection). Next, Dr. Reinhardt stands in a Dantesque Hell, a cavernous, rocky place, filled with flames, in which scores and scores of automaton robots march aimlessly. Subsequently and without warning, a door shining full of ethereal light is superimposed onto this hellish landscape; a floating human figure enters therein, and our crew emerges victorious from the black hole and sails toward a brightly shining planet as the screen fades and the credits roll.

Ultimately, and as was mentioned earlier, this vaguely hopeful and elysian ending situates The Black Hole firmly in the tradition of David & Goliath stories, which are essentially underdog tales where a person (or group of people) band together, pull themselves up by their bootstraps, and defeat the giants—both literal and metaphorical—in their lives. What is interesting, however, is how superficially these narratives align with the biblical narrative itself. While the vast majority of David and Goliath stories ask audiences to identify with the David character(s), the account of this famous clash between a shepherd boy and a giant in 1 Samuel is largely concerned with forcing its readers into the realization that we are not David characters; instead, we are more like the armies of Israel, the ones cowering in the background, forgetting that we are God’s own possession. One thing that films and stories like The Black Hole make abundantly clear, therefore, is that it is almost impossible for us to conceive of ourselves in this way, as weak, needy, and ineffectual creatures. We simply can’t imagine a world (or a future) in which we can’t save ourselves.

But The Black Hole, with its penultimate vision of Hell and occasionally breathtaking cinematography that remind us that we are incredibly, incomprehensibly tiny on a cosmic scale, does flirt with the idea. Perhaps this is one reason talks of remaking the film—which have been taking place for some time now— have stalled. It’s too dark, too off-putting, too terrifying. And I suppose it is . . . if there is nothing, or no one, beyond the veil.