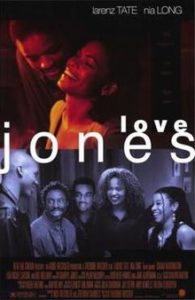

Nearly 25 years ago, the producers of the independent gem Love Jones had a modest and honest goal with its romance. They sought to make a modern film about African-American life that did not use violence and/or recreational drugs as story elements. The decade of the 1990s contains a strong selection of romantic black films, but many of the best of them like Poetic Justice, Jason’s Lyric, and Jungle Fever, have anchors in trauma and weakening vices, just as the moviemakers observed.

Nearly 25 years ago, the producers of the independent gem Love Jones had a modest and honest goal with its romance. They sought to make a modern film about African-American life that did not use violence and/or recreational drugs as story elements. The decade of the 1990s contains a strong selection of romantic black films, but many of the best of them like Poetic Justice, Jason’s Lyric, and Jungle Fever, have anchors in trauma and weakening vices, just as the moviemakers observed.

Avoiding those hazards made Love Jones a refreshing revelation that has garnered a dedicated following since 1997. If it only could have inspired more of a movement. The trouble is even an astute film fan would likely have difficulty counting the digits on both of their hands with movies since Love Jones that carry the same integrity of avoiding these negative tropes. In this writer’s opinion, the best and brightest to finally do so just landed this winter in the form of The Photograph. These two films shine not only for their modern and mature intentions but in the value of their words.

The Settings

Written and directed by Theodore Witcher, Love Jones takes place within the woven cross-sections of Chicago’s middle class. The Windy City has always been stitched as a quilt of ethnic neighborhoods and planted demographical flags. Without a stereotypical slum in sight, the characters navigate their surroundings with comfortable living conditions, clear education, and, most of all, an expressive sense of community. From the nightspots of large gatherings to the small businesses in between, the haunts and establishments are their own. They are used as places of expression and definition at the same time.

Here in 2020, that setting evolves to an even higher state of success in The Photograph with New York City as the nucleus. Double the comfort, talent, and cosmopolitan poshness from Love Jones. The modern half of filmmaker Stella Meghie’s timeline has characters working in high-level positions of respect in their field. The places they frequent exude more class than black films are used to occupying, which speaks to an intent to portray success and confidence in a very welcome way.

Here in 2020, that setting evolves to an even higher state of success in The Photograph with New York City as the nucleus. Double the comfort, talent, and cosmopolitan poshness from Love Jones. The modern half of filmmaker Stella Meghie’s timeline has characters working in high-level positions of respect in their field. The places they frequent exude more class than black films are used to occupying, which speaks to an intent to portray success and confidence in a very welcome way.

Never lost in both settings are two things: humble roots and culture. The Photograph exemplifies its roots with a flashback romantic arc that takes viewers from the polish of the Big Apple to the sunlit estuary waters outside of New Orleans, Louisiana. There, aspirations either stand firm or fly away from that southern comfort. In Love Jones, the shared struggling artist plights of its characters rise from the abrasive past of Chicago with hope and creativity at the forefront. In both films, the characters come from grit and pulled-up bootstraps.

The vibrancy of both settings comes out in the displays of culture. This is the first trait where Love Jones earned its revelatory status. From the reggae lounges and poetry night stage microphones to the stepper contests and record stores, shared black culture is alive and active. It fuels all passions. In The Photograph, the lead couple puts their black faces and voices out there as leaders in their respective fields of human interest journalism and museum curation. Culture is more than small talk. It’s a livelihood for social landscapes.

The Romance

It’s time to give names to the characters sauntering through these two settings. The proud and luminous Nia Long plays Nina Mosley in Love Jones. She is a photography assistant with skill and determination deserving of her own recognition and opportunities. Nina is coming off of failed engagement when she is swept off her apprehensive feet by the aspiring writer Darius Lovehall, played by Larenz Tate. They mesh their creative drives together as much as their bodies.

It’s time to give names to the characters sauntering through these two settings. The proud and luminous Nia Long plays Nina Mosley in Love Jones. She is a photography assistant with skill and determination deserving of her own recognition and opportunities. Nina is coming off of failed engagement when she is swept off her apprehensive feet by the aspiring writer Darius Lovehall, played by Larenz Tate. They mesh their creative drives together as much as their bodies.

With a touch slower building heat, Lakeith Stanfeild’s magazine writer Michael Block in The Photograph becomes interested in museum curator Mae Morton, played by Issa Rae. Like Nina, Michael is reeling from romantic failure when he meets Mae, the daughter of his latest city profile subject, and sees irresistible intrigue. The Photograph also doubles-down for a second love story spurred by its titular picture showing hints of a passionate side of Mae’s mother Christina (Chante Adams) that her daughter never knew.

Between both films, the romances evolve to become more about shared time and getting to know people than bedroom fireworks, though sexiness still simmers wonderfully throughout. In Love Jones, deep friend circles are involved, led by trusted confidantes for both Nina and Darius played by Lisa Nicole Carson and Isaiah Washington. Their characters are the blunt and honest sounding boards receiving and advising on uncertain feelings. For Mae and Michael in The Photograph, the shared soul-searching and soul-baring involves channeling the past as much as the present.

Enormous credit goes to the appeal of the actors. At the time, Larenz Tate was coming off of his volatile lead performance in Menace II Society and Nia Long was just a dreamy prize in Friday. Both showed massive potential and depth in stepping into a romance. The same can be said for Sorry to Bother You’s Lakeith Stanfield and the untested internet star Issa Rae. They too ran with this chance to impress with human tones far different than their previous roles and projects. Not one of them is merely eye candy. All occupy characters with vigor and flaws all the same. The kisses we watch mean more by what’s behind them and the actors convey that dramatically.

In both lead romances, attraction takes hold quickly and the euphoric rush is palpable and compelling. Both films have outstanding soundtracks that fuel all of this flow. Showing refined tastes matching their characters, jazz becomes a larger artistic presence than the hip-hop of each era. Love Jones features the tried-and-true rhythms of John Coltrane, Duke Ellington, and Charlie Parker while The Photograph employs composer and recording artist Robert Glasper for melodic instrumental score that would make Miles Davis proud.

In both lead romances, attraction takes hold quickly and the euphoric rush is palpable and compelling. Both films have outstanding soundtracks that fuel all of this flow. Showing refined tastes matching their characters, jazz becomes a larger artistic presence than the hip-hop of each era. Love Jones features the tried-and-true rhythms of John Coltrane, Duke Ellington, and Charlie Parker while The Photograph employs composer and recording artist Robert Glasper for melodic instrumental score that would make Miles Davis proud.

However, we all know, no matter the demographic, love is never simple or easy. Thanks in part to their settings and creative drives, the two sets of career-minded individuals in both movies carry uncertainty about their futures that create challenges for any higher intimacy or potential long-term relationships. Normal movie mechanics and tendencies would contrive weak reasons to split our lovers apart and even worse forced measures to bring them back together for unrealistic happy endings. Both movies are too smart for those mistakes and urges, and it’s readily apparent in their final and top trait of shared quality.

The Writing

With the high-minded intentions to be modern, progressive, and successful with their romantic realities, you would be hard pressed to find many romances with these levels of wisdom in their words. The writing is what separates Love Jones and The Photograph from the rank-and-file failures of trying to capture the black experience with life and love. Both movies thrive in their effectiveness for spoken emotions and active conversations.

With the high-minded intentions to be modern, progressive, and successful with their romantic realities, you would be hard pressed to find many romances with these levels of wisdom in their words. The writing is what separates Love Jones and The Photograph from the rank-and-file failures of trying to capture the black experience with life and love. Both movies thrive in their effectiveness for spoken emotions and active conversations.

The effect can be greatly seen when the couples first click in their movies. You’re never going to see a sexier pick-up moment than Tate’s Darius improvising a poem on stage named after his new target of attraction. The funny thing is the moment doesn’t seal the deal. It only opens the door to consideration from Long’s Nina. Likewise goes for the first date shared in The Photograph. By the time Stanfield’s Michael, midway through the night, asks if it’s too early to try for a kiss, the swoon is on. Yet, it doesn’t immediately launch more sizzle. It merely begins the true connection-building that follows. The paces of patience of those arcs are brilliant.

In very rare moments is anyone in Love Jones or The Photograph talking just to fill airtime. Their words are more measured and meaningful, from the hopeful lovers to the supporting characters interacting around. No talk is small and the dialogue in both movies seeks to express maturity. Much of that strength comes in the freedom granted to the filmmakers. Both Theodore Witcher and Stella Meghie were black creative voices given the fair opportunity to tell a legitimate black story with studio backing. Too often, writing room laboratories of other less genuine people churn out something plain and unimportant. Successes like these should be both applauded and multiplied.

In very rare moments is anyone in Love Jones or The Photograph talking just to fill airtime. Their words are more measured and meaningful, from the hopeful lovers to the supporting characters interacting around. No talk is small and the dialogue in both movies seeks to express maturity. Much of that strength comes in the freedom granted to the filmmakers. Both Theodore Witcher and Stella Meghie were black creative voices given the fair opportunity to tell a legitimate black story with studio backing. Too often, writing room laboratories of other less genuine people churn out something plain and unimportant. Successes like these should be both applauded and multiplied.

One Theodore Witcher monologue from Love Jones typifies the shared wisdom filling these two movies the best. It states:

“Romance is about the possibility of the thing. You see, it’s about the time between when you first meet the woman, and when you first make love to her; When you first ask a woman to marry you, and when she says I do. When people who been together a long time say that the romance is gone, what they’re really saying is they’ve exhausted the possibility.”

The Photograph and Love Jones operate with the language of those infinite possibilities. Love Jones has its core of poetry and The Photograph has its mystery of visual arts. Nothing in either love story feels telegraphed toward a foregone conclusion. There’s no magical switch for a line of “I love you” to change everything. Love Jones doesn’t use that sentence until the very end, and, in even more forthright fashion, The Photograph doesn’t say it at all. Both writers knew that more words have value than just the big L one. For both movies to unabashedly mold and earn beautiful stories of black love without any instant need for that kind of manufactured swell is truly something special.

Don Shanahan is a Chicago-based and Rotten Tomatoes-approved film critic writing on his website Every Movie Has a Lesson. His movie review work is also published on 25YL (25 Years Later) and also on Medium.com for the MovieTime Guru publication. As an educator by day, Don writes his movie reviews with life lessons in mind, from the serious to the farcical. He is a proud director and one of the founders of the Chicago Independent Film Critics Circle and a member of the nationally-recognized Online Film Critics Society.