At first thought, the genres of Horror and Western might not appear to have much to do with one another. Westerns evoke thoughts of a dusty America at the dawn of the modern age while horror conjures images of dank, shadowy basements and monsters with razor teeth. But if S. Craig Zahler’s brilliant film from last year called Bone Tomahawk is any indication, the two genres have a multitude of things to say to one another and should talk more often.

At first thought, the genres of Horror and Western might not appear to have much to do with one another. Westerns evoke thoughts of a dusty America at the dawn of the modern age while horror conjures images of dank, shadowy basements and monsters with razor teeth. But if S. Craig Zahler’s brilliant film from last year called Bone Tomahawk is any indication, the two genres have a multitude of things to say to one another and should talk more often.

The premise of the film is as simple as a sentence: Four heroes embark on a quest into the desert to rescue their loved ones from a tribe of savage cannibals. However, the richness of the work lies in the command of its tone and the understanding of its characters. It would be very tempting for a story like this, which could almost run parallel to stories about ancient knights rescuing fair maidens from fire-breathing dragons, to attempt to startle its viewers with cheap manipulations and exploit its subject matter for every inch of gory, gratuitous excess. What we see instead is a film that cares deeply about the characters and their quest, which devotes an extended amount of time to the establishment of their motivations as well as their regrets, and which withholds its graphic violence until the point in time when it will have as much impact on us as the viewer as it does on the characters who witness and endure it. We also see an extended exploration of justice, consequence, and the loyalty of brotherhood, not to mention the ever-present struggle against evil, both internal and external.

What makes it a western isn’t merely the setting and character tropes. And what makes it a horror story isn’t simply the monstrous villains or the moments of graphic gore. Both genres are known for archetypal settings and archetypal characters, and they both typically present fictional worlds with clearly defined moral codes which its characters either abide by or rebel against as a commentary on human nature. Zahler clearly has an understanding of these qualities, even if only by instinct, because his film is a fascinating example of both genres simultaneously. The emotional templates of justice codes and fair consequence which are present in nearly every western are in abundant supply here. But there are also more spiritual templates of redemption and, in particular leanings on the horror genre, the overcoming of unnatural evil.

Each of this story’s four heroes are so distinct and well-defined by an outstanding script that the viewer is deeply invested in the story’s outcome. When Brooder speaks about how many Indians he’s killed, claiming, “It’s not a boast, but a fact,” we can sense the mixture of pride and shame he carries with him because of it. When two characters come to a point where they know they are saying their final goodbyes, they do so without words, communicating with a couple of casual gestures the deep bonds of admiration and loyalty that they both shared. But perhaps the most impactful moment for me came when one particular character, upon approaching a threat he was unquestionably no match for, lifts his eyes to heaven and says, “You seein’ this? This is why I’ve been talking to you all these years. For a little help.” Whether or not he received that help, and what the ends all amounted to, resonated with me deeply and made it hard to shake away the film’s impact.

Each of this story’s four heroes are so distinct and well-defined by an outstanding script that the viewer is deeply invested in the story’s outcome. When Brooder speaks about how many Indians he’s killed, claiming, “It’s not a boast, but a fact,” we can sense the mixture of pride and shame he carries with him because of it. When two characters come to a point where they know they are saying their final goodbyes, they do so without words, communicating with a couple of casual gestures the deep bonds of admiration and loyalty that they both shared. But perhaps the most impactful moment for me came when one particular character, upon approaching a threat he was unquestionably no match for, lifts his eyes to heaven and says, “You seein’ this? This is why I’ve been talking to you all these years. For a little help.” Whether or not he received that help, and what the ends all amounted to, resonated with me deeply and made it hard to shake away the film’s impact.

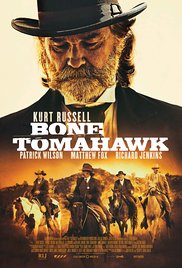

The performances are unanimously remarkable. Matthew Fox, playing somewhat against type, crafts a character who has beaten death enough times to feel overly confident, yet somehow knows his number is coming soon. Patrick Wilson blends fear and faith in an utterly naturalistic way for some of the movie’s bravest and most emotionally consequential sequences. Richard Jenkins, charming, endearing and vulnerable as a loyal sidekick on a mission well beyond his abilities, is the possibly the film’s most enjoyable element. And, as the film’s decent-hearted but tough-as-leather sheriff, Kurt Russell leads the pack. Nuff said.

It should be noted that the film contains very few moments of violence, but those moments are unforgettably graphic and intense. It is a visual equivalent of a burst of energy, which builds up almost unsustainably until just the right moment, then unleashes the fullest possible power to maximum effect. Thematically, there is one unforgettable death, which is as necessary to the story as it is immeasurably repulsive, and anchors both the threat of the evil at hand as well as the demand for fragile heroes to rise up and confront it. Bone Tomahawk is not reveling in the gory, violent carnage; it is displaying for both the characters and the audience the weight of loss and disgust of brutality, which make a story like this compelling.

I consider it to be no coincidence that the town from which our characters come is called “Bright Hope”. The entire movie could perhaps be seen as an extended metaphor for the ways in which we respond when evil threatens our hope. To we combat it with the authority of justice, with nervous but devoted loyalty, with confidence in our own skills and abilities, or with a sense of wounded-yet-healthy faith? Perhaps we need them all. Because there are evils in this world we can never understand, but which we can confront and, with a little help, inch our way back to hope.

I consider it to be no coincidence that the town from which our characters come is called “Bright Hope”. The entire movie could perhaps be seen as an extended metaphor for the ways in which we respond when evil threatens our hope. To we combat it with the authority of justice, with nervous but devoted loyalty, with confidence in our own skills and abilities, or with a sense of wounded-yet-healthy faith? Perhaps we need them all. Because there are evils in this world we can never understand, but which we can confront and, with a little help, inch our way back to hope.

Bone Tomahawk is a movie for the viewer who loves a strong script with richly realized characters, but who also doesn’t mind a glacial pace or moments of unflinching brutality. By the time all of the cards are on the table, the sufferings and triumphs our heroes endure are deeply and unforgettably affecting. Fans of either the horror or the western genre, but especially fans of both, owe it to themselves to check this one out.