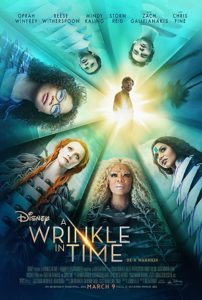

As a filmmaker myself, I completely understand that not everything is translatable from page to screen. Filmmakers are readers just like anyone else. Their interpretations or viewpoint on a story will look very different from each of our own. We all imagine things with our own individual lenses. That being said, we also should not expect a story’s very essence, core aesthetic, or character interpretations to be completely reformed either. That tragic loss of essence is, unfortunately, what happened with this adaptation of A Wrinkle in Time.

As a filmmaker myself, I completely understand that not everything is translatable from page to screen. Filmmakers are readers just like anyone else. Their interpretations or viewpoint on a story will look very different from each of our own. We all imagine things with our own individual lenses. That being said, we also should not expect a story’s very essence, core aesthetic, or character interpretations to be completely reformed either. That tragic loss of essence is, unfortunately, what happened with this adaptation of A Wrinkle in Time.

Before I unpack all that, I want to emphasize how much I adored Storm Reid as Meg. While her character (and pretty much most of the elements in the story) feels restrained and held back, Reid’s performance is incredibly authentic. She and Chris Pine are not on the screen together most of the film, but I invested and believed in their relationship. The climactic scene of the two them brought me to tears as it was so wholly natural and believable. Meg’s coming of age—seeing her father both as hero and fallible human—really held the story together.

Ava DuVernay is one heck of a woman and I know as a filmmaker her heart was in the right place creating this movie. She is completely committed to her craft and that is evident in all of her work. I must also note how awesome it is that she is a pioneer of sorts being the first woman of Color to oversee a film with a budget of this size. Awesome, but equally sad that it is 2018 and only happening for the first time.

I truly wanted to love this movie with all my heart, but there is too much holding it back from greatness. I actually read this series back in 2016, so the book is still pretty fresh in my mind. I read the first book in the series as both a child and an adult, so I believe I have a well-rounded view of what makes it a wonderful work of art to be appreciated at any age. I don’t buy into the argument that this is “just for kids” so it’s not worth adults discussing or interpreting. I share the C.S. Lewis belief, “A children’s story that can only be enjoyed by children is not a good children’s story in the slightest.”

I’m not shy about my disappointment with Disney’s creative decisions in the past five years. I won’t go into all of the reasons why, just the reasons that apply to this particular film. Chiefly, the profuse thematic sanitization and over-simplification, as well as the gratuitously glossy spectacle of current productions. A Wrinkle in Time is no exception to this, in fact, it has these issues in spades.

I’m not shy about my disappointment with Disney’s creative decisions in the past five years. I won’t go into all of the reasons why, just the reasons that apply to this particular film. Chiefly, the profuse thematic sanitization and over-simplification, as well as the gratuitously glossy spectacle of current productions. A Wrinkle in Time is no exception to this, in fact, it has these issues in spades.

We see this most obviously in the revision of the IT—Wrinkle’s abstract and terrifying villain. In the novel, IT is described as follows:

“an oversized brain, just enough larger than normal to be completely revolting and terrifying. A living brain. A brain that pulsed and quivered, that seized and commanded … IT was the most horrible, the most repellent thing [Meg] had ever seen, far more nauseating than anything she had ever imagined with her conscious mind, or that had ever tormented her in her most terrible nightmares.”

The IT’s modus operandi is to collect consciousness. To make everything and everyone part of Itself. To wash away flaw, individuality, creativity, doubt, or question. It brings out the worst in people, because only in our pain would we want to succumb to such an idea. Only when brought to our knees in despair do we wish to wash away everything about others and ourselves. This is partially why Meg is tempted by the IT with a supposedly prettier, smarter version of herself. IT doesn’t exist to make people “bad,” IT exists to further Itself by eradicating everything else.

In the film, we get the impression that the IT (also referred to as the darkness), just wants to make people jealous, angry, and violent—but that’s an oversimplification. Those things are a byproduct of the actual goal, which is to make everyone the same. To be just like IT. Why are people envious? Because they want something someone else has (a nice body, money, a relationship, possessions). Why do people go to war? Because they want something someone else has (money, oil, etc.), or to protect their own group-think (terrorism, extremist religion). Why did Cain kill Abel? The questions all lead to the same answer.

The IT is the sum of all envy. In making everyone just like the other, it’s satisfying that envy—or so it thinks. In truth, the envy can never be satisfied. It is as infinite as the universe, a black hole that only leads to more nothing, more darkness. I am reminded of Syndrome’s line in Pixar’s The Incredibles, “When everyone’s super, no one will be.” Syndrome and the IT ultimately have the same goal, and I think that could be said of all villains when stripping their motives down to the bone.

The IT is the sum of all envy. In making everyone just like the other, it’s satisfying that envy—or so it thinks. In truth, the envy can never be satisfied. It is as infinite as the universe, a black hole that only leads to more nothing, more darkness. I am reminded of Syndrome’s line in Pixar’s The Incredibles, “When everyone’s super, no one will be.” Syndrome and the IT ultimately have the same goal, and I think that could be said of all villains when stripping their motives down to the bone.

The three “Mrs.” show Meg and the others what the IT does to people. We see jealousy among teachers when someone gets promoted to principle, or Calvin’s dad yelling that he’s pathetic because of grades. I don’t mean to downplay these things because they are bad—but come on! The IT is the very heart (or brain, rather) of darkness. This film needed to show what that really looks like. It needed to trust children to handle the truth about terror, envy, and aggression. This primarily milquetoast presentation of reality is not enough.

When I read the climactic scenes of the IT in the book, I was utterly drawn in. With the film, I felt next to nothing. It’s just another overly CGI bad guy trying to hurt the hero and then losing to the hero with very little struggle. I garnered nothing of the spiritual and emotional depth L’Engle painted in those scenes. Writer Alissa Wilkinson titled her fantastic article about this film, “A Wrinkle in Time is a sincere, inspiring blockbuster for tweens. Why doesn’t it trust them?” and that is the main issue here. In oversimplifying the IT, (and frankly the entire weird, wonderful world of the book), we are implying that younger audiences need adults to help them digest stories. Hate to burst the bubble adults, but no, they don’t.

The characters overall feel held back from really “going there” with their individual darkness and issues. Meg’s faults are a huge theme in the book, but in the film, they only surface-level and kind of photoshopped so that they don’t appear too bad. I feel like this is a big mislead for children who wrestle with their faults on a daily basis. Which, by the way, is all of them.

I don’t know why they are so hesitant to go there in this production, when in the past Disney was known for showing true darkness, terror, despair. This is why we cry when Simba tries to wake up his dead father, or when his manipulative uncle places the burden of blame on him. This is why I get chills every time Beast holds Gaston by the throat atop his castle, only to show his enemy mercy in the end. Or, when Triton signs his name to Ursula’s contract to pay his daughter’s life-debt with his own life. Or, when Hercules descends to the pit of the underworld to resurrect Meg. The list goes on and on, and it is incredibly sad to me that most of Disney’s recent work shies away from revealing those realities because they believe audiences can’t or won’t handle the truth of what sin, loss, or envy really do to us. This isn’t just for the sake of reflecting reality, but also for the essential stakes that drive the story.

The other key issue of the film is the completely overt purge of the author’s spiritual themes and allegory, which stem from her strong personal faith. This is where we come back to the idea of a work’s essence being stripped away in an interpretation and being unacceptable. This film cut characters and scenes. Though I believe cutting out certain things was a mistake, most of it could be forgiven for the sake of cinematic presentation. The removal of the core allegory and spirituality of the book, however, is just shameful.

This removal doesn’t make sense for many reasons, but the most glaring reason is the fact that other spiritualities and spiritual leaders are referenced throughout the movie, but not a single Christian, besides Khalil Gibran. I’ll be honest, it lifted my heart to hear Gibran and Rumi (two of my favorite poets) quoted in the same scene, but why couldn’t all the quotes be shared WITH the Bible verses as they are in the book? Why is it acceptable to quote Buddha and Rumi, and give credit to Einstein and Ghandi, but totally omit Jesus and others of Christian faith listed in the book? Madeleine L’Engle includes both Christian and non-Christian figures, so if she was open, why couldn’t the film be? This omission isn’t just a slip of the pen. The removal of the Christianity from A Wrinkle in Time was done so with absolute intention, and this is as discourteous to the author as it is to the readers who connect with her work in a spiritual way. The audience should have been entrusted with the true story here and allowed to take or leave the thematic elements at their discretion. That is what storytelling is all about.

This removal doesn’t make sense for many reasons, but the most glaring reason is the fact that other spiritualities and spiritual leaders are referenced throughout the movie, but not a single Christian, besides Khalil Gibran. I’ll be honest, it lifted my heart to hear Gibran and Rumi (two of my favorite poets) quoted in the same scene, but why couldn’t all the quotes be shared WITH the Bible verses as they are in the book? Why is it acceptable to quote Buddha and Rumi, and give credit to Einstein and Ghandi, but totally omit Jesus and others of Christian faith listed in the book? Madeleine L’Engle includes both Christian and non-Christian figures, so if she was open, why couldn’t the film be? This omission isn’t just a slip of the pen. The removal of the Christianity from A Wrinkle in Time was done so with absolute intention, and this is as discourteous to the author as it is to the readers who connect with her work in a spiritual way. The audience should have been entrusted with the true story here and allowed to take or leave the thematic elements at their discretion. That is what storytelling is all about.

I have to be truthful, but I do not wish to depart on a low note. So, in the spirit of her openness and faith, I will conclude with a quote from the author herself that I feel summarizes the themes in the Wrinkle in Time novel and the Great Commission in one breath…

“We do not draw people to Christ by loudly discrediting what they believe, by telling them how wrong they are and how right we are, but by showing them a light that is so lovely that they want with all their hearts to know the source of it.”