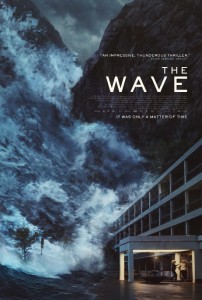

The Wave (Bølgen), Norway’s first disaster flick—and the country’s official submission to the Foreign Language Film category of the 88th Academy Awards—is a film that is intimately familiar with the well-worn tropes of its genre, a film that, instead of trying outdo its American counterparts by going louder, and more explosion-y (à la Michael Bay), shamelessly embraces the narrative beats and stock characters that have made disaster films so widely popular, showing that there is no reason to reinvent the wheel if there is still some magic left in a tried-and-true formula.

The Wave (Bølgen), Norway’s first disaster flick—and the country’s official submission to the Foreign Language Film category of the 88th Academy Awards—is a film that is intimately familiar with the well-worn tropes of its genre, a film that, instead of trying outdo its American counterparts by going louder, and more explosion-y (à la Michael Bay), shamelessly embraces the narrative beats and stock characters that have made disaster films so widely popular, showing that there is no reason to reinvent the wheel if there is still some magic left in a tried-and-true formula.

The film opens with newsreel and pseudo-documentary footage telling of a rockslide in early 1900s Norway that caused a tsunami and destroyed a small town; and, as the film’s tagline says, it’s “only a matter of time” before it happens again. Now, nestled in a small fjord in present-day northwestern Norway is the picturesque town of Geiranger, which is overshadowed by an unstable mountain that, should it fall into the waters of the fjord, would repeat the disaster of the previous century.

Serving as our protagonist and Geiranger’s prophet of impending doom is Kristian (Kristoffer Joner), a geologist who, along with his team, constantly monitors the mountain. In fact, the affable Kristian is so dedicated to his task of keeping the people of Geiranger safe that he often neglects his family. And perhaps this is one of the reasons that he is about to leave his current job to work in the oil industry. The day before he and his family leave town, however, something unusual happens: the mountain moves. It’s a subtle movement to be sure, but Kristian is convinced that the mountain is about to give way, hurling a massive tsunami toward Geiranger. Soon the inevitable happens. Haunting warning sirens sound throughout the fjord, and Kristian has ten minutes to get his family out of town before the wave hits.

The Wave stands out as one of the best disaster films in recent memory thanks in large part to the steady-handed direction of Roar Uthaug, of whom you will certainly be hearing more in coming years. (He has been a rising star in Norway for a few years now, and has been tapped to direct the upcoming reboot of the Tomb Raider franchise.) Uthaug knows where to put a camera in order to heighten frenetic action sequences, and he uses the edges of frames to create breathtaking and terrifying compositions. A particularly striking shot during one of the escape sequences exemplifies his deftness especially well. Running from the coming wave, Kristian and an injured woman are in the bottom right of the frame, while the tsunami barrels around the corner of the fjord, filling the leftmost section of the screen. This skillful use of the frame in its entirety is a mark of a truly talented director.

Moreover, Uthaug’s use of aerial shots in the film’s opening credits help audiences—especially non-Norwegian ones—to see and feel the beauty and potential horror the fjord harbors. We fly through a narrow inlet, surrounded by towering mountain ranges on both sides. After miles of traveling over some of the most lush, green mountain forests in all of the world, we arrive at the end of the fjord, where the city of Geiranger is burrowed down in the valley. Therefore, we understand from the opening moments of The Wave how trapped and isolated are the city and its inhabitants.

In an era where audiences have a voracious appetite for worldwide destruction sequences (occasionally we’re willing to settle for citywide disaster, provided that it takes place in New York City or Los Angeles), The Wave stands out as one of the more intimate films of its genre. Not only is the doomed city of Geiranger incomparably smaller than The Big Apple, but the tsunami scenes are also centered around the main characters so that the film avoids the disaster porn trap—wherein destruction on a grand scale becomes desensitizing, and scores of people with little to no connection to the narrative are meant to elicit sympathy from the audience as they are mercilessly killed off on screen—to which so many of its predecessors have succumbed. But the devastation and chaos in The Wave is truly impactful and feels terrifyingly real precisely because it is rooted in one family’s experience of a tragedy. Indeed, the film’s literal tsunami can even be read as a physical manifestation of Kristian’s tumultuous personal life and his inability to prioritize his loved ones, and it is here that the religious imagery of The Wave becomes eminently insightful.

The third act of the film follows Kristian as he seeks to reunite with his wife Idun (Ane Dahl Torp) and son Sondre (Jonas Hoff Oftebro), who were unable to make it out of town in time. Kristian is forced to reenter Geiranger, which has been baptized into death, even descending into death itself at one point, searching for his family on an overturned bus. His search and rescue mission takes on a symbolic meaning as he wades through the chaos and destruction in his own life in order to right the problems that he has created. In the film’s apotheosis, however, Kristian is asked to give more, to become an incarnation of love itself, which is willing to lay down its life for its friends. And here The Wave itself crests and crescendos, securing its spot in the annals of disaster film history.

The third act of the film follows Kristian as he seeks to reunite with his wife Idun (Ane Dahl Torp) and son Sondre (Jonas Hoff Oftebro), who were unable to make it out of town in time. Kristian is forced to reenter Geiranger, which has been baptized into death, even descending into death itself at one point, searching for his family on an overturned bus. His search and rescue mission takes on a symbolic meaning as he wades through the chaos and destruction in his own life in order to right the problems that he has created. In the film’s apotheosis, however, Kristian is asked to give more, to become an incarnation of love itself, which is willing to lay down its life for its friends. And here The Wave itself crests and crescendos, securing its spot in the annals of disaster film history.

1 comment