We accept the reality of the world with which we are presented.

– Christof, “The Truman Show”

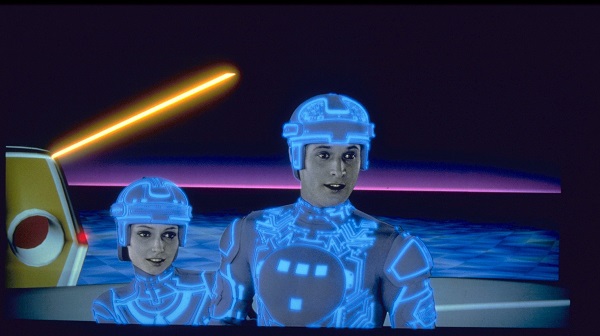

Do you remember The Truman Show? It’s almost two decades old now (in fact, my only copy is on VHS); as such, expect this article to contain spoilers. Perhaps you recall it, though. Jim Carrey played the title character in this film, about the ultimate reality show chronicling the life of a guy named Truman Burbank, who doesn’t know his every moment is being recorded and broadcast all over the world on T.V. It was given to us by Peter Weir, the film maker who brought us The Dead Poets Society and The Witness. It’s an excellent movie and I highly recommend watching it again (hopefully you’ve seen it, at least once, before reading this), because I think it speaks a lot of truth to our reality in this life, on this earth, at this time.

Do you remember The Truman Show? It’s almost two decades old now (in fact, my only copy is on VHS); as such, expect this article to contain spoilers. Perhaps you recall it, though. Jim Carrey played the title character in this film, about the ultimate reality show chronicling the life of a guy named Truman Burbank, who doesn’t know his every moment is being recorded and broadcast all over the world on T.V. It was given to us by Peter Weir, the film maker who brought us The Dead Poets Society and The Witness. It’s an excellent movie and I highly recommend watching it again (hopefully you’ve seen it, at least once, before reading this), because I think it speaks a lot of truth to our reality in this life, on this earth, at this time.

No, I’m not paranoid. I don’t believe we’re all unknowingly trapped in a giant dome made to look like somewhere in the real world and our every move is being captured on countless hidden cameras. But I do believe we’re constantly accepting the reality of a world we rarely question. I do believe we’re often fed lies, even when we’ve come looking for the truth. And I do believe that breaking out of that mind-set and the subsequent actions (or lack thereof) that result will, perhaps, be a great deal more difficult than anything we’ve ever done—and will require more courage than we probably thought we had.

Cue the sun

In the film, Truman has lived his entire life surrounded by falsehood. Almost everything is a manipulation to get him to do what his handlers want him to do. He wants to be an explorer, but they can’t let him leave; so his elementary school teacher tells him he’s “too late. There’s nothing left to explore.” When that doesn’t work, they stage a “death scene” where the actor playing his father (the only father Truman’s ever known and, as far as he knows, his real father) “dies” in a tragic sailing accident, rendering little Truman terrified of traveling over water. Sick? Yeah. But not more so than the T.V. viewers in the film enjoying this as entertainment. They feel sorry for Truman as you would feel sorry for a tragic character in a play. And, in the same way, continue to merely watch the story unfold, somehow as Truman’s fellow prisoners.

These viewers—the “normal, everyday people” in the film—are seemingly oblivious to the moral questions involved not only in using another human being as nothing more than a controlled commodity, but also in deliberately doing so without his consent. They don’t understand that Truman, in a very real sense, is walking through life completely alone. His mother, his best friend, and even his wife are nothing more than actors playing their respective roles. They’re paid to be Truman’s loved ones. It’s their job. The cold-hearted betrayal in this is almost beyond comprehension, yet Truman’s loyal fans and even the actors themselves accept it as a necessary part of the game. Perhaps he’s not quite the same as a real person to them. Perhaps amusement and paychecks are more important than any momentary twinges of conscience. Perhaps they just haven’t ever questioned the way things are. Don’t think for a second that they’re deliberately evil. They’re not; they, like Truman, have simply accepted the reality of the world with which they were presented. In some strange way, they, too, share a cell with the one they exploit.

These viewers—the “normal, everyday people” in the film—are seemingly oblivious to the moral questions involved not only in using another human being as nothing more than a controlled commodity, but also in deliberately doing so without his consent. They don’t understand that Truman, in a very real sense, is walking through life completely alone. His mother, his best friend, and even his wife are nothing more than actors playing their respective roles. They’re paid to be Truman’s loved ones. It’s their job. The cold-hearted betrayal in this is almost beyond comprehension, yet Truman’s loyal fans and even the actors themselves accept it as a necessary part of the game. Perhaps he’s not quite the same as a real person to them. Perhaps amusement and paychecks are more important than any momentary twinges of conscience. Perhaps they just haven’t ever questioned the way things are. Don’t think for a second that they’re deliberately evil. They’re not; they, like Truman, have simply accepted the reality of the world with which they were presented. In some strange way, they, too, share a cell with the one they exploit.

There are some people, of course, who are watching what’s happening to Truman and can see it for what it is. They’ve chosen to be uncomfortable rather than blind. It’s unpleasant and frustrating and sometimes even dangerous to be the minority shouting at the top of your lungs about injustice.

But we’re not ready for that discussion yet. First we need to talk about Truman.

Somebody help me, I’m being spontaneous!

Everyone who’s ever watched the film—and even the “viewing audience” obsessed with the show-within-the-show—want to see Truman escape. But it’s easy for all of us to miss just how difficult that is. There is a moment, quickly overshadowed by the drama of Truman’s father returning from the “dead” and claiming amnesia, where Truman finally begins to understand what he’s up against.

He’s attempting to explain to his best friend all of the strange things which have been happening; things that appear to indicate the world revolves around him somehow, and that “everyone seems to be in on it,” when the friend (in an attempt to convince Truman he’s imagining things) makes a jarringly true statement: “Think about it Truman… If ‘everybody is in on it,’ I’d have to be in on it too.”

He’s attempting to explain to his best friend all of the strange things which have been happening; things that appear to indicate the world revolves around him somehow, and that “everyone seems to be in on it,” when the friend (in an attempt to convince Truman he’s imagining things) makes a jarringly true statement: “Think about it Truman… If ‘everybody is in on it,’ I’d have to be in on it too.”

Next time you watch this film, study Jim Carrey’s face in that moment. The character he’s playing has just lost the best friend he never really had, and he can’t even react. He has to go on as if he still doesn’t suspect a thing. His one confidante was just revealed to be part of the enemy. He’s on his own.

At what point does it hit him that, in order to leave like he’s always wanted, he has give up everyone he loves? And at what point does he realize that everything he’s giving up is nothing more than the base comforts of a lifelong prison? But, despite the rabbit hole of horrors into which Truman must descend if he’s going to face the truth, he still emerges a hero. He overcomes his greatest fear, and every other obstacle designed to stop him. He almost dies in the attempt.

[pullquote]”You never had a camera in my head!”[/pullquote] And, yes, he finally escapes. It’s the moment, though, before he takes his final bow and walks off set that always gets me. Christof, the creator of the “show” (played brilliantly by Ed Harris), tries to talk Truman into remaining in his prison voluntarily. Nothing more than the disembodied voice of a person he’s never even met, Christof tries to tempt him with a promise of safety: “…in my world you have nothing to fear. I know you better than you know yourself.” Truman’s response is swift and to the point: “You never had a camera in my head!”

I love the defiance and the truth in that statement. But I also love the irony in the fact that it wouldn’t take a camera in Truman’s head to know him. It wouldn’t take a camera in his head to perceive what he wanted. It wouldn’t take a camera in his head to understand that holding him against his will for monetary gain and the entertainment of others is, and always will be, wrong. Yet Christof missed it—and how many others missed it as well?

I love the defiance and the truth in that statement. But I also love the irony in the fact that it wouldn’t take a camera in Truman’s head to know him. It wouldn’t take a camera in his head to perceive what he wanted. It wouldn’t take a camera in his head to understand that holding him against his will for monetary gain and the entertainment of others is, and always will be, wrong. Yet Christof missed it—and how many others missed it as well?

And therein stand the bars of their prison. They couldn’t see it. They weren’t listening. Their empathy was nowhere to be found.

That’s our hero shot.

But are we any better? Don’t we have moments…or longer than moments…in which we lack empathy? Do we take the time to actually know people before lumping them in with this or that group who “we” are against and, thereby, writing them off completely? Do we look for ways to really discover who they are? Or do we view them as unworthy of such time and energy? Do we see them as people at all?

[pullquote]Empathy is dangerous.[/pullquote] Or, upon close and honest inspection, do our attitudes toward them—refusal to listen in order to understand, denial of any real suffering, and quiet suppression of infinite value—look a little more dehumanizing than we’d like to admit? We are indoctrinated to believe that the world works a certain way by every voice we trust. In fact, we are presented with the above attitudes, leveled at whatever group that our group has been told to hate, as if they were “realities” on a constant basis. And we accept them. And, consequently, empathy may crumble the very foundations of our respective worlds! Our “truths” could be proven to be lies! Is it any wonder that we’d rather remain blindly imprisoned? Empathy is dangerous.

It seems like such a simple thing. But it is the key to the prison.

Don’t get me wrong, it can be painful diving into someone else’s life. It can turn your world completely on its head, seeing things from another person’s perspective. And, for these reasons, it can be frightening, as well. As I said earlier, breaking free will requires courage. It won’t necessarily be easy. I’d even go so far as to suggest that, perhaps (just perhaps), it is more difficult to escape our prison than it was for Truman to escape his. All the pain and loneliness and danger he had to face…Yet I think he had an easier time of it.

The film itself implies as much. Truman is the only one who escapes. “Let’s see what else is on” are the last words spoken before the credits roll, as Truman’s loyal fans cheerfully change their T.V. channels, having learned nothing.

The film itself implies as much. Truman is the only one who escapes. “Let’s see what else is on” are the last words spoken before the credits roll, as Truman’s loyal fans cheerfully change their T.V. channels, having learned nothing.

In all honesty, though, we should expect something so godly, something so Christ-like as empathy to be extraordinarily difficult. Who has shown more empathy than Jesus?

“Who, being in very nature God, did not consider equality with God something to be grasped, but made Himself nothing, taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness. And being found in appearance as a man, he humbled Himself and became obedient to death – even death on a cross!”

-Philippians 2:6-8, NIV

“For we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but we have one who has been tempted in every way, just as we are – yet was without sin.

-Hebrews 4:15, NIV

Any one of us may heave a sigh of relief at this moment, thinking we must be off the hook. We’re broken, we’re sinful, we cannot hope to be like Jesus and do what Jesus did. And yet…and yet…

“Do nothing out of selfish ambition or vain conceit, but in humility consider others better than yourselves. Each of you should look not only to your own interest, but also to the interests of others. Your attitude should be the same as that of Christ Jesus…

-Philippians 2:3-5, NIV

This is the moment I realized I was writing as much to myself as I was to anyone else. Because…What is His attitude? Well, I just quoted it above. And “making himself nothing” and “taking the very nature of a servant” are intense enough, but He also gave us commands which reflect His own actions: “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.” (Matthew 5:44) “Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who mistreat you…love your enemies, do good to them, and lend to them without expecting to get anything back.” (Luke 6:27,28,35)

Christ-like empathy goes further than probably most of us expected. And I cannot escape these questions:

Who are my enemies? Who are the people I don’t really see as people? Who are the ones I have deemed not worthy of relationship?

We accept the reality of the world with which we are presented.

What suffering have I written off as mere fiction…or somehow earned and deserved….or simply not worth my concern?

We accept the reality of the world with which we are presented.

Whose shoes have I refused to step into? To whom have I refused to listen?

We accept the reality of the world with which we are presented.

And why? Why would I see them this way?! Why would I have such an attitude toward people Jesus loved so much He died…?

We accept the reality of the world with which we are presented.

But what if we didn’t? What if we made a break for it? What if we escaped?

What if we looked for ways to discover who people are? What if we were for rather than against them? What if we chose to be uncomfortable rather than blind? What if we no longer accepted the lies, but only the Truth?

What if we looked for ways to discover who people are? What if we were for rather than against them? What if we chose to be uncomfortable rather than blind? What if we no longer accepted the lies, but only the Truth?

“Put on then, as God’s chosen ones, holy and beloved, compassionate hearts, kindness, humility, meekness, and patience, bearing with one another and, if one has a complaint against another, forgiving each other; as the Lord has forgiven you, so you also must forgive. And above all these put on love, which binds everything together in perfect harmony. And let the peace of Christ rule in your hearts, to which indeed you were called in one body…”

-Colossians 3:12-15, NIV

• • •

Thanks for reading Redeeming Culture. We’d like to welcome Abby back after a long hiatus! She’s a writer, editor, and dramaticist in Indianapolis, and we can’t wait to see her next article.

This my lovely wife to be is a wonderful write, insightful and caring. I am happy that no one found and pursued her the way I did because she is now mine, and no one else can have her. Be jealous I have gained a genius into my life and family.

That’s an interesting view of the movie and it’s message. I first didn’t really consider the whole dimension of empathy and human relationships so much, instead it made me ponder on society’s social games we accept without questioning, how our reality isn’t really defined by ourselves, just what reality even IS, how we’re being manipulated into staying ignorant and indifferent of the constraints forced upon us in many ways, through consumption and the illusion of security.

If you only consider these aspects though, it’s easy to become self-righteous, paranoid and bitter, only adding further to the division of us humans and the lack of empathy, which you rightfully addressed.

Truman is not playing victim here. He unlike most of us desperately needs and wants to seek a life beyond the norms and values others settle for under life’s pressures. The saddest thing is not that he has lived in an illusion but that he represents such a minute fraction of us who learn how to break out of the social conventions and norms that tend to dictate how we should respond to challenge and life; rather than embrace the changes that are possible so many of us would rather hide behind the comfortable boundary of cultural acceptance and social indifference that leaves us in a state of numb gridlock just hoping we can one day filter our lives past the traffic of the daily grind. All the while, we miss so much of what life could offer us if we took more risks, in faith, if we only had the Truman courage to give up our hearts for meaningful exploits and let go of what others think about us. Australia needs more Trumans because this country was founded on the courage, skill and determination of a few who went beyond into the unknown and forged into the impossible. The modern disease of luxurious apathy has left us high and dry of the inspiration we desperately need to break free of the suburbian desert so we can find ourselves again on mountains of challenge that pit our wills and desire against all life can throw at us when we reach for our impossible goals. Truman is not tragic but rather exceptional. He is what we all want to be – if only we can find the courage to face the past, the storms of the present and throw ourselves to the mercy of our deepest dreams for the future, maybe we will begin to value and appreciate the things that really matter to us, and things long left behind but not forgotten like our first loves. I want that one true thing back in my life, what about you?