When it comes to the sub-genre of “faith-based film” (defined here as movies made by Christians for the church and/or with evangelistic intent), filmmakers often find themselves on two ends of a spectrum. The more common tendency is for these films to be preachy, on-the-nose, and explicit in their message, sounding more like sermons than storytelling. On the other hand, some filmmakers have taken a more subtle approach, telling inspirational stories of “faith” with abstract, vague theology that potentially does more harm than good.

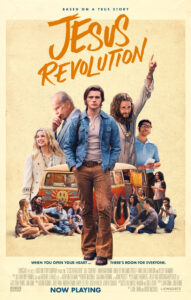

This isn’t to say that these films aren’t (on occasion) commendable or even without merit, but by their very nature, “faith-based films” struggle to find the balance between explicit communication of God’s Word and the necessity for visual storytelling. The filmmakers of Kingdom Story Company, the producers of I Can Only Imagine (2018), I Still Believe (2020), and American Underdog (2021), are not the only Christian filmmakers who have wrestled with this. However, their latest film, Jesus Revolution (2023), has given them an opportunity to tell a story where the explicit preaching of God’s Word is very naturally woven into the narrative—allowing them to, in the process, produce their best film yet.

This isn’t to say that these films aren’t (on occasion) commendable or even without merit, but by their very nature, “faith-based films” struggle to find the balance between explicit communication of God’s Word and the necessity for visual storytelling. The filmmakers of Kingdom Story Company, the producers of I Can Only Imagine (2018), I Still Believe (2020), and American Underdog (2021), are not the only Christian filmmakers who have wrestled with this. However, their latest film, Jesus Revolution (2023), has given them an opportunity to tell a story where the explicit preaching of God’s Word is very naturally woven into the narrative—allowing them to, in the process, produce their best film yet.

Jesus Revolution, set in southern California in the late 1960’s/early 1970’s, is essentially an ensemble piece. Over here, you have Greg Laurie (played by Joel Courtney), a military dropout crushing on Cathe (Anna Grace Barlow) and looking for something more to life. Over here, you have Chuck Smith (Kelsey Grammer), pastor of a dwindling church with a low opinion of modern hippies. And over here, you have Lonnie Frisbee (Jonathan Roumie), the hippie preacher who proposes that the two pastors work together to bring hippies into the church.

Jesus Revolution, set in southern California in the late 1960’s/early 1970’s, is essentially an ensemble piece. Over here, you have Greg Laurie (played by Joel Courtney), a military dropout crushing on Cathe (Anna Grace Barlow) and looking for something more to life. Over here, you have Chuck Smith (Kelsey Grammer), pastor of a dwindling church with a low opinion of modern hippies. And over here, you have Lonnie Frisbee (Jonathan Roumie), the hippie preacher who proposes that the two pastors work together to bring hippies into the church.

As the story progresses, and the stories of these characters intersect more and more, the church movement later known as “The Jesus Revolution” grows; but so does the conflict between characters. Laurie has maintained a grudge towards his mother (Kimberly Williams-Paisley) that he is forced to address. Smith realizes the prejudice in his own heart and faces resistance from his church elders about allowing hippies in church. Once he does, Frisbee leads bigger and bigger prayer services and even physical and spiritual healings, but he and Smith don’t always see eye-to-eye.

And this is to say nothing of other supporting characters and their subplots, such as Smith’s family, Frisbee’s wife, Cathe’s family, Time Magazine reporter Josiah (DeVon Franklin), and others who experience growth over the course of Jesus Revolution. At times, the story seems more suited for an episodic miniseries rather than one feature film. However, in terms of communicating a story with a beginning, middle, and end, with clear arcs for each character (as well as professional production value), this is perhaps the best work yet from Kingdom Story Company. The portrayal of the time period is authentic enough, the performances (and their dialogue) are believable enough, and the story itself is quite compelling.

And this is to say nothing of other supporting characters and their subplots, such as Smith’s family, Frisbee’s wife, Cathe’s family, Time Magazine reporter Josiah (DeVon Franklin), and others who experience growth over the course of Jesus Revolution. At times, the story seems more suited for an episodic miniseries rather than one feature film. However, in terms of communicating a story with a beginning, middle, and end, with clear arcs for each character (as well as professional production value), this is perhaps the best work yet from Kingdom Story Company. The portrayal of the time period is authentic enough, the performances (and their dialogue) are believable enough, and the story itself is quite compelling.

None of this matters, however, if the theology that Jesus Revolution is communicating is distilled down so much that it is nearly missing (or worse, unbiblical). As is perhaps normal for films in this market to do, in order to appeal to wider audiences, the way the film presents certain aspects of theology is perhaps “middle-of-the-road”: there is little to no mention, for example, of terms such as “charismatic,” “liberal,” or even specific Christian denominations. (The film is also careful to avoid mentioning Smith’s affiliation with the Emergent Church movement later in his life. Smith, in fact, seems the most conservative figure in the narrative.)

The film’s use of Scripture, however, makes it clear that God’s Word is the foundation for a movement like The Jesus Revolution. A sequence early on in the film intercuts Greg and Cathe at a concert (where an emcee proclaims that attendees should “define God the best you can”) with Frisbee talking to Smith at his house about how that generation is like “sheep without a shepherd” (Matthew 9:36), and “How can they believe in the One of whom they have not heard?” (Romans 10:14) The film makes clear that true faith is not vague belief in a nonspecific God, but faith that comes by the hearing of God’s Word (Romans 10:17).

The film’s use of Scripture, however, makes it clear that God’s Word is the foundation for a movement like The Jesus Revolution. A sequence early on in the film intercuts Greg and Cathe at a concert (where an emcee proclaims that attendees should “define God the best you can”) with Frisbee talking to Smith at his house about how that generation is like “sheep without a shepherd” (Matthew 9:36), and “How can they believe in the One of whom they have not heard?” (Romans 10:14) The film makes clear that true faith is not vague belief in a nonspecific God, but faith that comes by the hearing of God’s Word (Romans 10:17).

Throughout the film (usually in situations where Smith, Frisbee, or even Laurie are preaching), there are many references to specific passages of Scripture, New and Old Testament, never twisted out of context. God is preached as triune, consisting of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit; there is a clear Gospel presentation in the film’s first half; and in some scenes, before a pastor begins preaching, they proclaim from the pulpit: “This is truth. This is life. This is God’s Word. Let’s open it together.” In fact, when spontaneous healing does occur later on in the film, there are concerned looks among congregants, ominous music, etc., almost as if the film is portraying this as dangerous (in the sense that it can take the church’s focus away from God’s Word, which is Smith’s primary concern).

Throughout the film (usually in situations where Smith, Frisbee, or even Laurie are preaching), there are many references to specific passages of Scripture, New and Old Testament, never twisted out of context. God is preached as triune, consisting of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit; there is a clear Gospel presentation in the film’s first half; and in some scenes, before a pastor begins preaching, they proclaim from the pulpit: “This is truth. This is life. This is God’s Word. Let’s open it together.” In fact, when spontaneous healing does occur later on in the film, there are concerned looks among congregants, ominous music, etc., almost as if the film is portraying this as dangerous (in the sense that it can take the church’s focus away from God’s Word, which is Smith’s primary concern).

The use of Scripture and solid Biblical theology in Jesus Revolution is not only portrayed very naturally in the film, since these characters are literally preaching it; it’s also unfortunately uncommon in many faith-based films today. Should this film do well financially, perhaps there will be yet another trend (similar to the aftermaths of The Passion of the Christ in 2004 or God’s Not Dead 10 years later) of Christian films that actually have sound Christian doctrine in them filling the marketplace.

No matter how much the film makes, however, we pray that Christian moviegoers are relying on the Bible itself, not a film, to form their theology and share it with others. If Jesus Revolution can prompt more people (including non-Christians) to do that, then perhaps that’s the biggest success of all.