“But you looked at me and I could see your mother in your eyes

I thought about the things she lost and how she always cries

And how your daddy tries to fight the truth with Bombay gin

And I knew we’d keep goin’ to try to end up less like themOh, the sins of the father

Drag like anchors on the kid

Come on, let’s go a little farther

All the way to anywhere more than this”—“Anchors” by Will Hoge

Director Gavin O’Connor makes movies about fathers and sons. More to the point, he makes movies about fathers who have multiple sons and who enjoy, to put it mildly, aberrational relationships with them. One of his first mainstream films was Miracle, the story of the 1980 gold-medal winning US Hockey team, and his most recent film (as of this writing) is the Ben Affleck-fronted action thriller, The Accountant. These films are worlds away from each other in many regards, but they talk about one common theme: hard-driving fathers and the sons they create.

Director Gavin O’Connor makes movies about fathers and sons. More to the point, he makes movies about fathers who have multiple sons and who enjoy, to put it mildly, aberrational relationships with them. One of his first mainstream films was Miracle, the story of the 1980 gold-medal winning US Hockey team, and his most recent film (as of this writing) is the Ben Affleck-fronted action thriller, The Accountant. These films are worlds away from each other in many regards, but they talk about one common theme: hard-driving fathers and the sons they create.

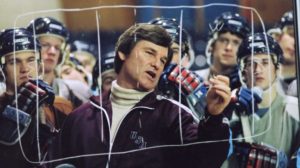

In Miracle, the father is Herb Brooks, the legendary college hockey coach who took a rag-tag group of amateur American hockey players and forged a team that toppled the Soviet stalwarts. It’s a very workmanlike film which has become O’Connor’s trademark. Nothing fancy, nothing showy, just blue-collar work behind and in-front of the camera. He’s very similar to Brooks in that way. He’s a man driven by the desire to grind his way to success.

The twenty young men who take the ice are the sons here. Certainly, they’re not Brooks’ biological sons—but what a movie that would be!—but by the time the film’s third act arrives, they’ve come to reflect their “father’s” approach to the game. Work, grind, rinse, repeat. It’s a sports film, so of course the finale takes place on the ice, giving rise to Al Michael’s legendary call as time expired with the US victorious over its geopolitical foe:

“Do you believe in miracles? YES!”

But the success comes at a cost. Brooks is not kind to his team. The film shows a man who has little-to-no-interest in his “sons’” well-being. He pushes them to the breaking point, emotionally, mentally, and physically, every chance he gets. “I’ll be your coach, I won’t be your friend,” he promises them at their first meeting. And he’s true to his word. It’s probably an overstatement to say he’s cruel, but not much of one. And it’s his hardness, his almost-cruelty that prods his team to greatness, to immortality. Perhaps his greatest talent as a coach is the ability to hand-pick the players who will have the right reaction to his coaching style. The unstoppable force of Brooks collides with the immovable object of his team’s collective personalities and the result is enough kinetic energy to overpower the unbeatable foe.

But the success comes at a cost. Brooks is not kind to his team. The film shows a man who has little-to-no-interest in his “sons’” well-being. He pushes them to the breaking point, emotionally, mentally, and physically, every chance he gets. “I’ll be your coach, I won’t be your friend,” he promises them at their first meeting. And he’s true to his word. It’s probably an overstatement to say he’s cruel, but not much of one. And it’s his hardness, his almost-cruelty that prods his team to greatness, to immortality. Perhaps his greatest talent as a coach is the ability to hand-pick the players who will have the right reaction to his coaching style. The unstoppable force of Brooks collides with the immovable object of his team’s collective personalities and the result is enough kinetic energy to overpower the unbeatable foe.

The Accountant tells a completely different kind of story, but with a familiar cast of characters. It has a weirdly-maniacal father, referred to as “the colonel,” and it has multiple sons, actual flesh-and-blood ones this time. But where Miraclestops short of calling Brooks abusive, The Accountant makes no bones about the colonel’s manifest unfitness to raise children. He drives them beyond discipline and correction to something pathological and controlling. He’s not raising sons; he’s creating and shaping a special breed of men. It’s never particularly clear what kind of men he wants his sons to be, except that he wants them to be deadly and uncompromising.

And he gets his wish. I’ll try to avoid spoilers since, unlike the previous film this one is not based on true events that are enshrined in US Sports history, but, suffice to say, his sons are remarkable men, and not in a particularly good way. But they are singularly unique in their fictional world, both highly sought after for their well-honed skills and their impeccable discipline in applying those skills.

And he gets his wish. I’ll try to avoid spoilers since, unlike the previous film this one is not based on true events that are enshrined in US Sports history, but, suffice to say, his sons are remarkable men, and not in a particularly good way. But they are singularly unique in their fictional world, both highly sought after for their well-honed skills and their impeccable discipline in applying those skills.

Where’s the line between a father who compels his sons to excellence and one who abuses them into perfection? When you see someone, or a team of someones, achieve unparalleled excellence, what kind of father did they have? What role did their father play in that achievement?

O’Connor’s films take the role of a father very seriously, even if they don’t always give us fathers worth emulating. They also plainly advance the thesis that a father has the potential for enormous influence over his sons, for good and for evil. But more than that they present the role of father as one that is irreplaceable in a man’s development. Fathers and sons are impossibly complicated, but, at their heart, they’re also completely straightforward: the father invests, shapes, guides, and points the way towards the son’s future; the son reacts, responds, resists, and ultimately chooses a path. And, like it or not, takes a piece of his father with him, which means the father also gives at least a little piece of himself to the son. That’s how it works. Which piece the father gives, be it Brook’s blue-collar ethic or the colonel’s pathology, is up to him. How much of it the son embraces, or rejects, is his own choice. A son is not his father (or father-figure), nor is he simply the passive product of a father-centric formula, but he is father’s son, and he always will be.

O’Connor’s films take the role of a father very seriously, even if they don’t always give us fathers worth emulating. They also plainly advance the thesis that a father has the potential for enormous influence over his sons, for good and for evil. But more than that they present the role of father as one that is irreplaceable in a man’s development. Fathers and sons are impossibly complicated, but, at their heart, they’re also completely straightforward: the father invests, shapes, guides, and points the way towards the son’s future; the son reacts, responds, resists, and ultimately chooses a path. And, like it or not, takes a piece of his father with him, which means the father also gives at least a little piece of himself to the son. That’s how it works. Which piece the father gives, be it Brook’s blue-collar ethic or the colonel’s pathology, is up to him. How much of it the son embraces, or rejects, is his own choice. A son is not his father (or father-figure), nor is he simply the passive product of a father-centric formula, but he is father’s son, and he always will be.

Brian Thomas is a former pastor, turned law student; a former Baptist, turned Eastern Orthodox. He and his wife, Kellye, have five children and live in Northwest Arkansas where he attends the University of Arkansas Law School. Brian is the cohost of the This Heretical Life podcast and tweets occasionally. He does not play hockey and is bad at math.