“Film is truth, 24 times a second.” –Jean Luc-Godard

We live in a world of displacement.

We live in a world of displacement.

Through the efforts of cultural, societal, and technological change, we move and breathe day after day as those forced towards awareness. Being in the know is today’s equivalent of power, a veritable social status. We lord our influence with facts, articles, statements, and refutations. Yet because of this, we are irrevocably displaced from ourselves. We fear that we need to know, but do we know exactly what we need to know? And why we need to know it? Yet knowledge continues to be unable to fill the void of our displacement.

The sacred has become profane, a harbinger of a past age of relics, customs, and oppressions. Yet where is the blood in things? Have we lost the art of confession?

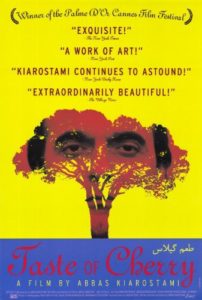

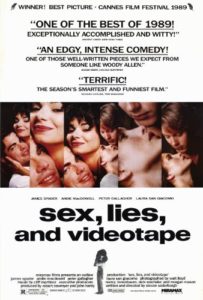

In Taste of Cherry (1997) and Sex, Lies, & Videotape (1989)–two respective winners of the prestigious Palme d’Or prize–we see two directors struggling with what it means to confess and how the very act of filmmaking becomes confession in itself. In the past, philosophers would argue over the power and effect of words, that language was the way in which we would become aware of ourselves. Naming came from knowing and knowing would come from the language in which we would inhabit. Yet language on its own has always been the struggle between ourselves and what is truly real. Herein lies the gift of film: by telling us stories in images rather than in words; film forms us by seeing rather than by knowing. Through the lens, not the mind, we become known and aware. In each of these films, the lens acts as a confessor, showing us truth, 24 times a second.

Taste of Cherry tells the story of Badii (Homayoun Ershadi), an older middle-aged Iranian man with considerable wealth, as he cruises about and around the outskirts of Tehran searching for someone to assist him in his suicide. His plan and request are simple: to kill himself come nightfall but have someone come the next morning to bury him. The location and time are already picked, and Badii offers a large sum of money for anyone willing to carry out the task. In his search, Badii finds three characters who go for a ride with him in his car as he tries to convince them to carry out the job. The first is a young Kurdish soldier, shy and innocent, who flees from his car upon being frightened by Badii’s request. The second is an Afghani seminarian, who declines to assist because of his convictions, and is unable to dissuade Badii with religious arguments or sympathy. The last man is an affable Turkish professor who works as a taxidermist at a natural history museum. He recalls a time when he, too, wanted to commit suicide, yet realized again the preciousness of life when he tasted mulberries. In the end, however, he agrees to help Badii with his task, saying that he needs the money for his child who is sick.

Taste of Cherry tells the story of Badii (Homayoun Ershadi), an older middle-aged Iranian man with considerable wealth, as he cruises about and around the outskirts of Tehran searching for someone to assist him in his suicide. His plan and request are simple: to kill himself come nightfall but have someone come the next morning to bury him. The location and time are already picked, and Badii offers a large sum of money for anyone willing to carry out the task. In his search, Badii finds three characters who go for a ride with him in his car as he tries to convince them to carry out the job. The first is a young Kurdish soldier, shy and innocent, who flees from his car upon being frightened by Badii’s request. The second is an Afghani seminarian, who declines to assist because of his convictions, and is unable to dissuade Badii with religious arguments or sympathy. The last man is an affable Turkish professor who works as a taxidermist at a natural history museum. He recalls a time when he, too, wanted to commit suicide, yet realized again the preciousness of life when he tasted mulberries. In the end, however, he agrees to help Badii with his task, saying that he needs the money for his child who is sick.

The story is told tightly, yet it’s rambling nature, caught vividly by the rumbling of the Range Rover along the glorious Tehrani countryside, feels like a lyrical elegy. Without a soundtrack, we are entranced and notice brightly the sounds of children playing in a verdant valley, construction vehicles grinding against the rocky terrain, and the horns of cars passing by. We the viewer know we are witnessing the game of death, a confession from a desperate man, a plea for his life to end, yet we can’t help but be enraptured by the wonder in which we are playing it in. Kiarostami tells his story in a minimalist mold, a filmic equivalent of a Tom Stoppard play or a poem by Stephen Crane, by keeping his camera on one person in the car at a time, rarely showing multiple people in the frame. For a director known for his long takes and leisure with silence, Kiarostami forces us towards isolation. We cannot be distracted by backgrounds or moving parts, we are forced to reckon with the slow drip of words from a man bent on murdering himself. In doing so, Kiarostami forces us into our own selves, into our own conversations we have when we find ourselves alone, say, in a car, asking “what keeps me from death?”

Told in a similar minimalist style, though dashed with much more humor and without the obdurate obliqueness, is Steven Soderbergh’s Sex, Lies & Videotape. In this film we are told the story of a quartet of characters caught in, well, sex, lies, and videotape. In this foursome are Ann, a glowing, proper, southern woman who is unhappily married to her husband, John. John is a successful and domineering lawyer, who is cheating on Ann with her sister, Cynthia. Cynthia, a painter and bartender, is the back side of the coin of her sister Ann, flaunting her sexuality, promiscuity, and open lifestyle. In this triangle of deception visits Graham, a former fraternity brother of John from college, who now lives and looks like a drifter, long bohemian hair and dark oversized shirts. Graham arrives with a new confessional identity, to be unreservedly honest to everyone at all times about all things.

Told in a similar minimalist style, though dashed with much more humor and without the obdurate obliqueness, is Steven Soderbergh’s Sex, Lies & Videotape. In this film we are told the story of a quartet of characters caught in, well, sex, lies, and videotape. In this foursome are Ann, a glowing, proper, southern woman who is unhappily married to her husband, John. John is a successful and domineering lawyer, who is cheating on Ann with her sister, Cynthia. Cynthia, a painter and bartender, is the back side of the coin of her sister Ann, flaunting her sexuality, promiscuity, and open lifestyle. In this triangle of deception visits Graham, a former fraternity brother of John from college, who now lives and looks like a drifter, long bohemian hair and dark oversized shirts. Graham arrives with a new confessional identity, to be unreservedly honest to everyone at all times about all things.

Throughout the film, our characters further and further intertwine deeper into one another’s personal lives. John frequently leaves the office and/or ignores clients to go and make love to Cynthia during the afternoon. Ann and Graham, who immediately take to each other upon Graham’s arrival, spend more and more time together while Cynthia and John are away at work or at play. They go to lunch, where Graham reveals he is now impotent, and they go apartment shopping together. One day, while making a surprise visit to see Graham at his new apartment, Ann discovers a stack of videotapes piled around the television, each with a woman’s name on its side. Graham reveals they are all confession tapes of sorts, women talking about their past sexual lives, feelings, and experiences. He reveals to her that he masturbates to them while he’s alone. Ann, disgusted, flees Graham’s apartment. The next day, Cynthia, who has also taken somewhat of an interest in Graham, stops by to ask why her sister got so spooked and left in such a fuss the day before. Cynthia, having become calloused toward her and John’s ongoing affair, and remorseful for the way she has been treating her sister, allows Graham to videotape her. After Ann finds Cynthia’s pearl earring next to her bed the next day, she returns to Graham to confront him about messing with her life and feelings and forces him to videotape her as well.

Soderbergh tells this story with a masterful sense of objectivity. Our characters are forced to work through their decisions and confusions on screen, we see the denial seep through their faces. Shot in 35mm film, a grainy and intrusive stock, Soderbergh films conversations in extreme close-ups. The pores of our characters seem to pimple out from the film. Sweat becomes an instinctual, primal feeling, eyes and cheeks are turned into felt things. The skin of our characters turns into a codex of their very souls, we see the deep-seated feelings on their faces, and those unsaid recollections, built up from years of lies and subversions, come spilling out on the screen. Soderbergh shows us small moments of bodies in motion, the tingling of fingers around a glass, the movement of eyes that follow the tracing of a hand, how the corners of the mouth twitch in slow motion in response to sexual pleasure. It is a work of titillating filmmaking in every regard, intensifying the confessions we hear on screen. Soderbergh frames the story in the Garden District of Baton Rouge, the town and neighborhood in which I currently live and call home. He captures perfectly the languid sense of space, the vibrant greenery adorning the inside of houses, and the bright light which falls down white-walled rooms. It is the perfect setting for our jumble of characters, a blank space for their reservations to boil and rise, while life glows and grows brightly from just outside. It is a suitable blank stage for our actors to wrestle on, while we, the audience, sit back and watch comfortably from view.

Soderbergh tells this story with a masterful sense of objectivity. Our characters are forced to work through their decisions and confusions on screen, we see the denial seep through their faces. Shot in 35mm film, a grainy and intrusive stock, Soderbergh films conversations in extreme close-ups. The pores of our characters seem to pimple out from the film. Sweat becomes an instinctual, primal feeling, eyes and cheeks are turned into felt things. The skin of our characters turns into a codex of their very souls, we see the deep-seated feelings on their faces, and those unsaid recollections, built up from years of lies and subversions, come spilling out on the screen. Soderbergh shows us small moments of bodies in motion, the tingling of fingers around a glass, the movement of eyes that follow the tracing of a hand, how the corners of the mouth twitch in slow motion in response to sexual pleasure. It is a work of titillating filmmaking in every regard, intensifying the confessions we hear on screen. Soderbergh frames the story in the Garden District of Baton Rouge, the town and neighborhood in which I currently live and call home. He captures perfectly the languid sense of space, the vibrant greenery adorning the inside of houses, and the bright light which falls down white-walled rooms. It is the perfect setting for our jumble of characters, a blank space for their reservations to boil and rise, while life glows and grows brightly from just outside. It is a suitable blank stage for our actors to wrestle on, while we, the audience, sit back and watch comfortably from view.

Yet what makes Taste of Cherry and Sex, Lies, & Videotape so prophetic is that both films turn the act of filmmaking back onto the viewer, forcing us to grapple with its revelatory power in each of their final acts. The lens of the camera becomes a probe that unveils our subjectivities and invites us to a confession that our characters share.

In the final act of Taste of Cherry, we follow Badii as he traverses to his pit in which he has dug for himself. He drives back along our familiar route, passing along the wind swept hills outside Tehran in the dark, the small car lights of his vehicle bouncing along in the dark. Arriving to his final resting spot, his chosen grave of grief, Badii lies down in his hole. A thunderstorm brews overhead and we lie waiting in the dark, lighting flashing like camera lights, revealing Badii lying dormant in his pit, full of remorse, wonder, and silence. After long moments of darkness, where it seems we are traveling down to the depths with Badii himself, Kiarostami breaks the fourth wall to reveal behind the scene camcorder footage of Taste of Cherry being filmed. We see the crew, sprinkled across the green hills, some setting up tripods, some hiding in the grasses with boom mics for sound. Various members stand about, some pointing, some smoking cigarettes, some holding their hands up to block the sun. Here in these final images stands Kiarostami himself, directing it all, sunhat on and mic in hand. “We’re here for a sound take,” he says. He turns, his sunglasses glinting a reflection of the camera lens, facing us with the instrument of the very documentation we are witnessing. We cut to black while the credits roll to the sound of Louis Armstrong’s “St. James Infirmary”, a jazz funeral standard, the only song to be played in the film.

In the final act of Taste of Cherry, we follow Badii as he traverses to his pit in which he has dug for himself. He drives back along our familiar route, passing along the wind swept hills outside Tehran in the dark, the small car lights of his vehicle bouncing along in the dark. Arriving to his final resting spot, his chosen grave of grief, Badii lies down in his hole. A thunderstorm brews overhead and we lie waiting in the dark, lighting flashing like camera lights, revealing Badii lying dormant in his pit, full of remorse, wonder, and silence. After long moments of darkness, where it seems we are traveling down to the depths with Badii himself, Kiarostami breaks the fourth wall to reveal behind the scene camcorder footage of Taste of Cherry being filmed. We see the crew, sprinkled across the green hills, some setting up tripods, some hiding in the grasses with boom mics for sound. Various members stand about, some pointing, some smoking cigarettes, some holding their hands up to block the sun. Here in these final images stands Kiarostami himself, directing it all, sunhat on and mic in hand. “We’re here for a sound take,” he says. He turns, his sunglasses glinting a reflection of the camera lens, facing us with the instrument of the very documentation we are witnessing. We cut to black while the credits roll to the sound of Louis Armstrong’s “St. James Infirmary”, a jazz funeral standard, the only song to be played in the film.

Similarly so is the final act of Sex, Lies, & Videotape. After being videotaped by Graham, Ann comes homes to John and demands for a divorce, ultimately confessing that she, too, recorded a tape with Graham. John then storms over to Graham’s apartment where he punches him and throws him out on the front porch while he stands in his former friends living room to watch his beleaguered wife’s confession. Also shot on camcorder footage, Ann confesses that she is unsatisfied with her marriage, and has never felt any form of sexual satisfaction. Graham asks if she ever thinks about having sex with other men, and she confesses that she had thought of him. Ann then grabs the video camera from Graham’s hands and turns the lens on him. Graham resists being filmed but is ultimately moved towards confession and recounts being plagued and haunted by an ex-girlfriend from college, his reason for distancing himself from others and relationships. The two slowly move closer together, until Ann takes Graham’s hands and places them on her face, moving them like shadows across her skin. Graham gets up off the couch and turns the camcorder off, leaving us in the bright buzz of white noise that John stands silhouetted against in Graham’s apartment.

Breaking the fourth wall is often seen as the lazy artist’s way out. It is the “it was all a dream!” turn, the half-baked flick of the wrist that seems to make all the preceding drama go mute. Roger Ebert himself blasted Taste of Cherry for this decision, writing, “And why must we see Kiarostami’s camera crew – a tiresome distancing strategy to remind us we are seeing a movie? If there is one thing ‘Taste of Cherry’ does not need, it is such a reminder: The film is such a lifeless drone that we experience it only as a movie” (citation). Yet Kiarostami’s directorial decision here is not the result of lazy indifference, or a creative get-out-of-jail-free card, it is a statement on the power of film: an assertion that film is truth. Like Badii we live in a world of boxes, of trappings and of interiors. We frame ourselves in our cars, in our bathtubs, and in our beds. We live life in molds of isolation, from the womb in which we emerge to the coffin, or hole, we bury our self in. Yet just as Badii closes his eyes and drifts off into the blackness, so film enraptures us by descending us into the blackness only to bring us out to the light.

Breaking the fourth wall is often seen as the lazy artist’s way out. It is the “it was all a dream!” turn, the half-baked flick of the wrist that seems to make all the preceding drama go mute. Roger Ebert himself blasted Taste of Cherry for this decision, writing, “And why must we see Kiarostami’s camera crew – a tiresome distancing strategy to remind us we are seeing a movie? If there is one thing ‘Taste of Cherry’ does not need, it is such a reminder: The film is such a lifeless drone that we experience it only as a movie” (citation). Yet Kiarostami’s directorial decision here is not the result of lazy indifference, or a creative get-out-of-jail-free card, it is a statement on the power of film: an assertion that film is truth. Like Badii we live in a world of boxes, of trappings and of interiors. We frame ourselves in our cars, in our bathtubs, and in our beds. We live life in molds of isolation, from the womb in which we emerge to the coffin, or hole, we bury our self in. Yet just as Badii closes his eyes and drifts off into the blackness, so film enraptures us by descending us into the blackness only to bring us out to the light.

Soderbergh, like Kiarostami, understands this power. Told on the wave of the video revolution of filmmakers that was to come, Soderbergh taps into the prophetic potentional film has at conveying the truth in its subjects in its most stripped down form. We do not need grand film prints and epic scales to convey truth and tell important stories. We need only a lens and the daring vulnerability to look straight into it. When we stare at the lens, as Soderbergh does, or dare to look behind it, as Kiarostami does, we are met with the holy rites that ring from a confession booth, that from death, sin, and decay come rebirth and springs of life. The lens of the camera is a call of repentance, it demands the actor shed the husk of himself and reveal the closet of his soul, the underbelly of his inclinations, and the reason behind his chaos. It is a savage act, a call for man to reckon with the glass of an indifferent machinery, and come to terms with the lies and stories that we all tell ourselves and why. To be human is to live in enlarged aspect ratios, for life itself has become a performance piece. We are all on stage now. Look into the camera.

Thomas Zak is a film worker and writer living in Baton Rouge, LA. He has had poems published in DigBR, Wonder South, and Fathom Magazine.