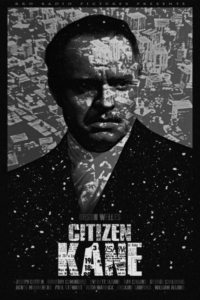

Orson Welles’ mythic masterpiece about an American tycoon’s rise and fall feels remarkably relevant for America in 2016. Despite only winning one Oscar out of its nine nominations and being panned at the box office, Citizen Kane is arguably the greatest film of all time (though Hitchcock’s Vertigo bumped it from its top spot in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll). I first heard of Citizen Kane from a friend in middle school, who told me it was supposed to be the best movie ever made, but it was, quote, “sooooo boring.” Having watched the film recently, its pacing is remarkably brisk and the dialogue is both fresh and fleet—this is certainly not a slow-paced or tedious film. The lighting, edits, and cinematography are all interesting, right from the opening sequence of a series of shots slowly closing in on a lit window in the fortress of Xanadu, protagonist Charles Foster Kane’s personal palace and a symbol of the pursuit of wealth and power—seemingly impressive, yet empty and lonely inside.

Beginning at the deathbed of Kane, the film’s non-linear narrative centers on a reporter trying to figure out the meaning of Kane’s final words: “Rosebud.” The story jumps back and forth through time, setting the foundation for so many future films featuring flashbacks and non-linear scripts. Kane inherits a literal gold mine, a fortune saved for him while being raised by a banker and guardian, Thatcher, whose memoirs tell of Kane’s origins and rise to power. After becoming a wealthy newspaper tycoon in the vein of William Randolph Hearst, Kane turns to politics, running for governor and subsequently losing due to a scandal with a mistress, beginning the spiral that will ultimately lead to his isolated demise. Others also share their collective memories of Kane, including his former best friend Jedidiah (Joseph Cotten, in his first film appearance) and second ex-wife Susan (Dorothy Comingore). Few have rosy recollections of the man, and none can determine the meaning behind the enigmatic Rosebud. (If you don’t know what “Rosebud refers to, I’ll leave that discovery unspoiled for you.)

Citizen Kane might be the quintessential American film in centering on a self-made man, a rags-to-riches story, serving as both a celebration and a critique of individualism and exceptionalism (the original working title of the film was The American). One can see hints of Kane in contemporary films like There Will Be Blood, The Social Network, and The Wolf of Wall Street. We are sympathetic with Kane, mostly due to Welles’ excellent performance, but we also see him as the villain within his own story. As he accumulates fame and wealth, he also ends up isolated and disconnected from others. A sequence with his first wife, Emily (Ruth Warrick), emphasizes this disconnection. As their romance begins, Charles and Emily share a meal at a small table together, sitting so close they’re almost touching. As Kane’s newspaper business grows, so does the physical distance between husband and wife, ending with Emily spitefully reading the paper of a competitor at the far end of an enormous dining room table. The scene is both comical and sad, and a masterful understanding of the medium of cinema. Welles uses image and montage, editing and camera angles, to show us, not tell us, that Charles and Emily are drifting apart. As his newspaper empire grows, his love for his wife dissipates.

That this scene all happens in a matter of minutes while still retaining its emotional heft is just another indicator of Welles’ genius in direction and filmmaking. Welles was only 25 years old when he made Kane, with an unprecedented amount of freedom from RKO studios—he directed, produced, acted, and co-wrote the film, and was given autonomy in choosing his actors and crew, many of which came with him to Hollywood from the Mercury Theater. In some ways, the film set Welles on a trajectory similar to Kane’s: a rise and fall in the public eye, with a wake of broken marriages behind him. He has a legacy of great successes and significant failures, a masterful artist beset with numerous trials and obstacles throughout his life. Despite all the excellent films that followed during his long career, Citizen Kane will likely be the film that remains Welles’ greatest legacy.

“You know…if I hadn’t been rich, I might have been a great man.” Kane’s confession is a brief moment of self-awareness for a man bent on dominating others and obsessed with personal success and power. Citizen Kane serves as a filmic version of the life of Solomon, a man whose own lust for wealth and women defied his God-given wisdom. Much like a narrative version of Ecclesiastes or Proverbs, Citizen Kane’s story offers us wisdom about the realities of wealth, such as its tendency to isolate, its unrelenting demand for more, and its disconnection from happiness or pleasure. The heart of the American ethos hasn’t changed much since 1941—we could use a reminder from Citizen Kane about our public leaders, our understanding of media, our consumer culture, and our need for authentic and grace-filled relationships in order to thrive. If you haven’t seen Citizen Kane, I’d encourage you to seek it out; if you have, consider a second viewing in the near future. We could all use a bit of filmic proverbial wisdom.