What do we think about when we engage art? When we gaze at a painting, do we appreciate it for its beauty – the images we see and perceive – or for the craftsmanship it took to create it? Depending on a person’s tastes and tolerance for any given art form, it’s probably a combination of both. Film as art is no different. For the masses movies are generally appraised based upon the stories they tell, the themes conveyed, and the performances delivered by its actors. For those with a deeper interest in film these aspects are still important, but there is also typically an added layer of evaluation that weighs the achievements of those behind the camera – the how and the why a sequence is captured at a particular angle, for example – and the stories that chronicle the making of – a director or writer’s inspiration for the film, the themes he or she wishes to convey, or the greater context in which the film is conceived. Looking at film through this perspective, then, is why we remember the works of great directors like Orson Welles, Alfred Hitchcock, Akira Kurosawa, and Yasujiro Ozu and consider them true artists.

What do we think about when we engage art? When we gaze at a painting, do we appreciate it for its beauty – the images we see and perceive – or for the craftsmanship it took to create it? Depending on a person’s tastes and tolerance for any given art form, it’s probably a combination of both. Film as art is no different. For the masses movies are generally appraised based upon the stories they tell, the themes conveyed, and the performances delivered by its actors. For those with a deeper interest in film these aspects are still important, but there is also typically an added layer of evaluation that weighs the achievements of those behind the camera – the how and the why a sequence is captured at a particular angle, for example – and the stories that chronicle the making of – a director or writer’s inspiration for the film, the themes he or she wishes to convey, or the greater context in which the film is conceived. Looking at film through this perspective, then, is why we remember the works of great directors like Orson Welles, Alfred Hitchcock, Akira Kurosawa, and Yasujiro Ozu and consider them true artists.

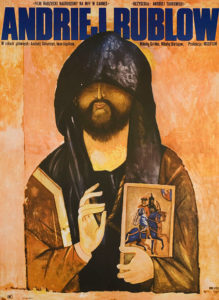

I would add to that list Andrei Tarkovsky who may not be as well known as the four listed above but has certainly been just as influential (especially on the work of my favorite living filmmaker, Terrence Malick). He was an artist in the vein of Carl Theodor Dreyer and Ingmar Bergman who openly and honestly wrestled with religion and had a penchant for long takes, sparse storytelling, and contemplative pacing. He’s probably best known today for his two sci-fi masterpieces Solaris and Stalker or his autobiographical filmic poem Mirror, but it’s one of his earliest films that remains his most enduring. Andrei Rublev is a medieval epic that chronicles the life of one of Russia’s most famous religious iconographers and the tumultuous nation in which he lived. And yet, Tarkovsky’s film is a less strict biographical account of the real Andrei Rublev than it is a meditation on Russian society filtered through the pain of the past, the influence of Christianity on a nation’s history, and the struggle inherent in artistic pursuits.

This last point is perhaps what elevates Andrei Rublev above simply adhering to the tradition of cinematic epics (though it does succeed in this area as well – its set pieces, costumes, sweeping cinematography, and choreographed battle sequences are some of the grandest and most accomplished in all film history). From its opening, unrelated prologue featuring an ambitious inventor who takes to the sky in a primitive hot air balloon, Tarkovsky establishes his film as one highlighting the fruit of creative minds. And, as the elated inventor first marvels at the desolate countryside below only to plummet disastrously to the ground as his own invention fails him, Tarkovsky also suggests that choosing to create comes at a great cost.

The rest of Andrei Rublev, in its sprawling narrative comprised of semi-related vignettes, follows a handful of other creators who each approach their art and handle their setbacks differently. Andrei (Anatoly Solonitsyn) is one of three wandering monks who serve as iconographers as they traverse the Russian landscape in search of cathedrals to paint. While Andrei is renowned for his superior skills and seeks to portray the good in humankind, his friend Danil (Nikolai Grinko) is more pragmatic in his approach and their companion Kirill (Ivan Lapikov) desires recognition for his work and even abandons the faith consumed with jealousy of Andrei’s talents. Then, there is the old painter Theophanes the Greek (Nikolai Sergeyev) who holds a rather cynical view of humankind and as such sees his work as a burden. Foma (Mikhail Kononov) and Andrei’s other protégés are skilled, yet stubborn, impatient, or indifferent with their brushes. And finally, Boriska (Nikolai Burlyayev), a young boy who crosses paths with Andrei at a crucial juncture in the monk’s life, serves as the most significant fellow creator he encounters on his travels. Andrei has given up on his own art feeling uninspired and seeking atonement for a sin he committed by taking a vow of silence when he meets the son of a respected bell-maker who died in the plague.

Young Boriska only enters the film in its final third, but the story of how he risks shame, punishment, and even execution for the chance to create is easily the beating heart of Tarkovsky’s work. When messengers from the royal prince come searching for the boy’s father to cast a bell for a new cathedral, he boldly offers to oversee the project himself. Boriska is often overconfident and harsh as he orders the workers around though they are much older and far more experienced than him. But, as the project nears completion, the boy’s head begins to fill with doubt. What if it breaks easily? What if it doesn’t ring? All the while, the silent Andrei watches on skeptically alongside the other villagers. But, when the bell does ring the crowd erupts into cheers of delight as Boriska collapses to the ground in relief. Inspired by the boy’s ambition and commitment to his craft, the monk runs to his side, breaks his silence, and vows to continue painting, his redemption now complete.

Choosing to create can come at a great cost indeed. There is risk – risk of failure, that the creation might be misused or abused, that the creation might betray its creator. Throughout the film, Andrei suffers great loss as he pursues his passion for painting – friendships that cave under the weight of envy, apprentices that storm off after disagreements, and even the loss of some of his works as a cruel invading force sets fire to a cathedral that he and his guild spent months painting. But, in the end, Tarkovsky reveals that the struggle and the pain are more than worth it. After nearly three and a half hours of stark black-and-white imagery, the director brilliantly and jarringly cuts to an epilogue of sorts as the camera pans over a number of the iconographer’s real frescos in eye-popping color. It’s a sequence full of emotion as we are given a glimpse into what Andrei’s efforts have yielded. And, what a beautiful glimpse it is!

Choosing to create can come at a great cost indeed. There is risk – risk of failure, that the creation might be misused or abused, that the creation might betray its creator. Throughout the film, Andrei suffers great loss as he pursues his passion for painting – friendships that cave under the weight of envy, apprentices that storm off after disagreements, and even the loss of some of his works as a cruel invading force sets fire to a cathedral that he and his guild spent months painting. But, in the end, Tarkovsky reveals that the struggle and the pain are more than worth it. After nearly three and a half hours of stark black-and-white imagery, the director brilliantly and jarringly cuts to an epilogue of sorts as the camera pans over a number of the iconographer’s real frescos in eye-popping color. It’s a sequence full of emotion as we are given a glimpse into what Andrei’s efforts have yielded. And, what a beautiful glimpse it is!

It’s safe to assume the Andrei of Tarkovsky’s film creates because he too was created by one who took great risk in breathing his creation into being. Somewhat surprisingly, then, the tale of a monk who lived hundreds of years ago in medieval Russia serves as a charge to each and every one of us to dare to create, to push through the pain in pursuing art to add to the beauty. And, that is precisely what Tarkovsky has done with Andrei Rublev, a tremendously gorgeous and affecting film. And, not only does it boast powerful themes and performances from its actors and a host of masterful filmmaking flourishes, it also provides a unique depiction of the very creative process that produces the art we appreciate. For that, it will always be remembered for the classic it is.