Missed in history stories can be some of the best and most interesting stories. And when the story is from the perspective of a minority group often overlooked by a culture’s texts, it can be truly fascinating.

Missed in history stories can be some of the best and most interesting stories. And when the story is from the perspective of a minority group often overlooked by a culture’s texts, it can be truly fascinating.

Nat Turner’s slave rebellion is one such story. We may have heard his name in high school history or a college American history class, but it is often relegated to a paragraph or footnote. When the issue of slave revolts are brought up, the most common name associated with this movement is the revolt led by John Brown, on Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. If you look up the Wikipedia entries of both John Brown and Nat Turner, Brown is called an abolitionist, Turner is called a slave. Brown was hailed as a hero and had Ralph Waldo Emerson and Victor Hugo lobbying for his pardon from leading a rebellion to overturn the institution of slavery. Turner was given a trial but was quickly hung before his body was beheaded, flayed, and quartered as an example to others who would rebel. The treatment of both men seems radically incongruous until you realize John Brown was a white man and Turner was a black man.

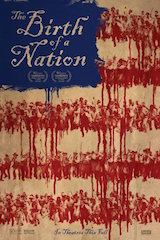

Making his directorial debut, Nate Parker set his ambitions high in bringing Nat Turner’s story to the big screen for the first time in The Birth of a Nation. Set in the 1830’s in Southampton County, Virginia, Turner’s life in slaveholding Virginia looks better than most. Samuel Turner, Nat’s owner and played by a chin-beard wearing, gin-swilling Armie Hammer, is a mostly kind master. Having grown up with Nat, Hammer is an almost benevolent slave owner. He treats Nat well and even lets him preach to the other slaves. He even obliges Nat to marry a slave girl, Cherry(Aja Naomi King), given to Turner’s sister (Katie Garfield). When local preacher and fellow drunk, Reverend Walthall, extends an offer for Nat to preach to other owner’s slaves, Samuel rides with Nat and also pockets some coin. Nat is told to preach a message to keep the slaves in line and “pacify” any disobedience to their earthly masters.

The movie suffers gravely from some particularly ham-fisted choices of imagery, as well as the development of Nat’s ultimate conviction to take up arms against his masters. Whether it’s Parker’s greenness as a director or the passion and urgency he feels in getting his message across, the images aim for obvious, pandering simplicity over artful interpretation or originality. The most blatant example being a climactic, grotesque lynching. The score for most of the movie has been gentle female vocals and strings in quieter moments and lots of thumping drums when things grow more intense. Yet when the lynching takes place there is a dissonant shift to a modern rendition of “Strange Fruit”. It’s both an odd-choice musically and hackneyed. It feels like a trailer for the movie’s message, immediately eliminating any sense of gravity from an important and gruesome moment.

Not every moment in the movie is this blunt or boiler plate. The real-life Nat Turner was considered to be a prophet and the movie, to its credit, stays true to his prophetic preaching with wall-to-wall Scripture. His belief in the fidelity and truth of the Bible motivate him to preach the good news to his fellow slaves. The same conviction will eventually convince him of the need to stand up in rebellion. The white slave owners seem to find his faith almost quaint, convinced he is doing their bidding. Elucidated to perfection in the best scene of the movie–how I wish there were more–Nat is invited to pray when local slave-owning families get together for dinner. His prayer is packed full of deep, biblical conviction, yet his prayer is a menacing call-to-action to resist slavery; all while the slave owners smile warmly and offer oblivious “amens”.

Not every moment in the movie is this blunt or boiler plate. The real-life Nat Turner was considered to be a prophet and the movie, to its credit, stays true to his prophetic preaching with wall-to-wall Scripture. His belief in the fidelity and truth of the Bible motivate him to preach the good news to his fellow slaves. The same conviction will eventually convince him of the need to stand up in rebellion. The white slave owners seem to find his faith almost quaint, convinced he is doing their bidding. Elucidated to perfection in the best scene of the movie–how I wish there were more–Nat is invited to pray when local slave-owning families get together for dinner. His prayer is packed full of deep, biblical conviction, yet his prayer is a menacing call-to-action to resist slavery; all while the slave owners smile warmly and offer oblivious “amens”.

Nate Parker has gone on record multiple times declaring Nat Turner a hero. The movie frames Turner’s reading of the Scriptures, to break the bonds of oppression and rise up to strike “the head of the Serpent” as a righteous reading of God’s Word in comparison to the skewed and wicked reading of the Scriptures by whites to enslave their fellow black brethren. This dichotomy is troubling. The movie’s largest thematic vacuum is Scripture never being used for its intended purpose, to bring life. Instead, it is wielded as a tool for moral justification of the subjugation of humans or the violent uprising of the oppressed. Missing is a balanced look at the heart of Christ both for the oppressed slave and the unrighteous oppressor. In fact, Christ is both explicitly and implicitly absent from most of the religious language the movie employs. It’s discomforting, but I do not believe it is an intentional choice by Parker, but a glaring and disappointing omission.

However, if umbrage is to be taken with Parker’s claim of Turner’s heroism, then we as a primarily white movie-going audience have much to repent of. We can no longer hold figures like William Wallace, Tyler Durden, the MacManus brothers, or even Neo in such high regard. All of these heroic protagonists embraced violence as a means to liberation, some religiously motivated, some not. Why then, are we so quick to resist a slave’s belief in God’s blessing on his efforts to liberate an oppressed people? The answers are not so easy and the movie chooses not to land comfortably on an easy, safe answer. Parker’s movie is not great; it’s okay. However, it is to be commended for not tying a modern, complacent bow on either Nat’s story or the issues of racism and oppression, and makes Birth of a Nation, despite its flaws, an important movie everyone should see.