Whodunits require a lot from both creator and viewer. This is because they’re actually carved from two stories, woven together as a “double narrative”— one is the secret, behind-the-scenes, cloak-and-dagger story of what really happened to cause the death of the rich person and the inciting incident; and the other is the overt story that the audience is actually told about detectives using clues and logic and comically large magnifying glasses and such to figure out the secret story.

Whodunits require a lot from both creator and viewer. This is because they’re actually carved from two stories, woven together as a “double narrative”— one is the secret, behind-the-scenes, cloak-and-dagger story of what really happened to cause the death of the rich person and the inciting incident; and the other is the overt story that the audience is actually told about detectives using clues and logic and comically large magnifying glasses and such to figure out the secret story.

In good whodunits, you can glimpse the secret story through the gaps in the overt story; enough that you know, looking back, you could’ve potentially assembled all the pieces if you worked at it, but not enough that you feel bored from figuring it out ten minutes in.

In great whodunits, the overt and secret stories collide in one dramatic, action-packed scene, and when they do the movie kind of unravels. Everyone is a suspect and the tension gets ratcheted way up, and you’re making guess after guess about what’s really going on and missing it over and over, but it doesn’t bother you because even though you’re wrong the movie makes you feel really smart about being wrong and sort of demands that you have fun with it.

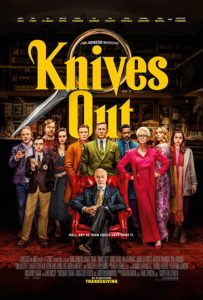

Knives Out is that story-collision scene. But instead of five minutes, it’s expertly doled out over the course of the whole entire movie.

Knives Out is that story-collision scene. But instead of five minutes, it’s expertly doled out over the course of the whole entire movie.

And what a movie it is. Fun, yes, but with depth and gravitas that makes it even more thrilling. A quirky but momentous score. Sublime writing and direction; there was absolutely nothing—not a solitary frame, not a half-glance, not a single word said as an aside—that didn’t contribute to the climax in some meaningful way. It’s tightly-wound and kinetic, thoughtful and hilarious. You come out feeling like a genius even though you didn’t figure any of it out before the reveal. And it’s a rare film that’s fun, but that I also can’t stop thinking about.

If you haven’t seen it yet, I must insist that you watch it before I spoil it because it’s a wonderful experience, and you shouldn’t let anyone steal that from you. Spoilers follow, so this is your last chance. In the meantime, let me just make a note for myself to avoid the pun “whodonut” in this article at all costs.

The Profoundly Unlikable Thrombey Family

The Thrombey Family might seem to their neighbors as genial and well-to-do before the contents of Harlan’s will send them desperately careening into a frantic and disgusting greed, but they’re actually eight deeply, profoundly, painfully unlikable people from the very start; and if you’re not sure about that, just ask yourself why Marta wasn’t invited to Harlan’s funeral.

The Thrombey Family might seem to their neighbors as genial and well-to-do before the contents of Harlan’s will send them desperately careening into a frantic and disgusting greed, but they’re actually eight deeply, profoundly, painfully unlikable people from the very start; and if you’re not sure about that, just ask yourself why Marta wasn’t invited to Harlan’s funeral.

When she arrives and talks to the bereaved family, Linda tells her that she wanted Marta to be invited to the funeral, but she was “outvoted.” Which would be fine…except that both of her siblings say the exact same thing. Not only are they lying about wanting to invite Marta to save face, they’re throwing their family under the bus to do so. The proverbial knives are, so to speak, already out.

They don’t remember what Marta’s nationality is. They make promises to “take care of” Marta and her family, which seems like a selfless gesture until that promise is put to the test. They use her as a prop for their political arguments. Marta is a balm for their self-righteousness, their siblings are expendable except when they are necessary, and their own grandmother (to whom they have yet to even offer condolences by the end of the film) is roundly ignored.

They’re vile, vile people. They aren’t antagonists; no, this film handles enemies far more deftly than that. They aren’t even important enough to be the villains. But they are definitely people we love to hate.

They’re vile, vile people. They aren’t antagonists; no, this film handles enemies far more deftly than that. They aren’t even important enough to be the villains. But they are definitely people we love to hate.

That’s why we have such a positive reaction to the final scene, where Marta stands on the balcony, staking her claim with a coffee cup. It’s so fun to watch when the kind, wholesome person ends up on top. We identify with Marta as one who was wronged, and so we feel a catharsis, a vindication when they win; and that’s what this film gives us.

Sadly, we’re fooling ourselves by placing us in her place. We aren’t Marta, or even her mother or sister. We’re the cruel, insipid, murderous, uncaring Thrombeys.

Oh sure, maybe we’re the “liberal snowflake” who is apologetic about yet still enables the others; or maybe we’re the “nazi teen” who only hurts people who are far away from him. But on my worst days, that’s a best-case scenario.

I know my heart; I’ve been the shiftless publisher who only cares about my work. I’ve been the all-business boss who thinks I’ve pulled myself up by my bootstraps and wants everyone to know it, and I’ve been the one whose affections are too easily pulled aside even as I play the sanctimonious ascended one. I’ve been the double-dipping “influencer” who needs praise while simultaneously robbing the glory from God Himself. I’ve uncaringly kept my nose upturned at those I felt “better than.” And I’ve certainly been the conniving, double-crossing prevaricator. I have committed all the sins that the Thrombeys do; not to the depth that these profoundly petty, pusillanimous poster-children of puking perfidy do, by the grace of God—but then again, in some cases maybe worse.

I know my heart; I’ve been the shiftless publisher who only cares about my work. I’ve been the all-business boss who thinks I’ve pulled myself up by my bootstraps and wants everyone to know it, and I’ve been the one whose affections are too easily pulled aside even as I play the sanctimonious ascended one. I’ve been the double-dipping “influencer” who needs praise while simultaneously robbing the glory from God Himself. I’ve uncaringly kept my nose upturned at those I felt “better than.” And I’ve certainly been the conniving, double-crossing prevaricator. I have committed all the sins that the Thrombeys do; not to the depth that these profoundly petty, pusillanimous poster-children of puking perfidy do, by the grace of God—but then again, in some cases maybe worse.

We like stories of cathartic retribution when we’re able to put ourselves in the position of the righteous one, but we’ve done nothing to prove that we belong in that category and everything to prove that we don’t. Then we try to claim the identity of the persecuted and downtrodden, even as those around us truly do suffer. Blanc would have a field day with the undeniable evidences of our malfeasance.

Meanwhile, Marta defeats them all…. by being kind.

Playing to Build a Beautiful Pattern

Part of the brilliance of Knives Out is the subversion of the typical whodunit tropes: instead of a hard-boiled, aloof northern detective, Blanc is a deep-fried, genial southerner, for instance. The perpetrator can’t lie, and is even revealed in the first act of the film. But probably the best subversion of expectations that Rian Johnson executes is always placing Marta with the “antagonist” of the film. Blanc is the first antagonist, when it becomes clear that he’s actually trying to find her in his investigation; he draws her into his circle before it’s even revealed to the audience how Harlan really died.

Part of the brilliance of Knives Out is the subversion of the typical whodunit tropes: instead of a hard-boiled, aloof northern detective, Blanc is a deep-fried, genial southerner, for instance. The perpetrator can’t lie, and is even revealed in the first act of the film. But probably the best subversion of expectations that Rian Johnson executes is always placing Marta with the “antagonist” of the film. Blanc is the first antagonist, when it becomes clear that he’s actually trying to find her in his investigation; he draws her into his circle before it’s even revealed to the audience how Harlan really died.

But before the story flips to paint Blanc as an ally, he is replaced as the antagonist by Ransom; then seeming to be an affable but still somewhat self-serving friend. We eventually find out that he’s not the friend he appears to be, but by that point Marta is already wound up in his web.

Marta rides the edge of the stress of her secret throughout the film; in fact, as things begin to unravel, we notice more that her phone screen is cracked, a reflection of her inability to fully communicate with the people around her without breaking. But while the knives come out when Thrombeys get desperate, when Marta gets desperate, she kindly and faithfully does her job.

In fact, the family doesn’t even comprehend this kindness. Ransom couldn’t conceive of anyone being genuinely good enough to try and save the life of someone who could destroy her with a single piece of paper, and it becomes his downfall when Marta tries to save Fran. Linda can’t imagine that Marta was genuinely friends with Harlan and not a gold-digger or secret lover (well, “boinker”). When Marta is kind, promising to take care of them, they think she means it in the condescending and insincere way they had meant it, and they reject it. Walt gets the closest to a sliver of understanding, but even he just sees her kindness as foolishness, wielding that perceived stupidity as a crowbar against Marta’s family by threatening to withhold resources that legally already belonged to Marta anyway.

Marta Cabrera exemplifies Ephesians 4:

“[We shouldn’t be taken in or confused] by human cunning, by craftiness in deceitful schemes. Rather, speaking the truth in love, we are to grow up in every way into him who is the head, into Christ…”

—Ephesians 4:14–15, ESV

Despite the dire situation she finds herself in, Marta is truthful. And, sure, she’s kind of forced into it by her “regurgitative reaction to mistruth,” but the story implies that dishonesty hasn’t really occurred to her: Harlan himself has to coach her in selective truth-telling in order for her to make it through the interrogation. She’s no practiced dissembler; she’s an honest person, even in difficult situations.

Despite the dire situation she finds herself in, Marta is truthful. And, sure, she’s kind of forced into it by her “regurgitative reaction to mistruth,” but the story implies that dishonesty hasn’t really occurred to her: Harlan himself has to coach her in selective truth-telling in order for her to make it through the interrogation. She’s no practiced dissembler; she’s an honest person, even in difficult situations.

But more so, she’s kind, outmaneuvering even the vicious Ransom by being utterly guileless; outplaying everyone with her kind heart. Seeking not to conquer and be victorious over the others, but to “make a beautiful pattern.”

The overt story of God’s truth and the hidden story of God’s love collide here, and this is where everything starts going bonkers. Because the reason we love Marta’s character in Knives Out is that the way she lives with these Profoundly Unlikable People, with her unwavering kindness and truth, is an echo of who God made us to be.

It’s the way Jesus conquered the world, and it’s how He’s doing it now: not through crafty maneuvering or open warfare, not through covert spies or devastating bombs, but by coming down to save unlikable people and send His people out with truth and love for everyone. He makes His beautiful pattern out of the lives of those He saves, the kindness He empowers, and the truth that real vindication and catharsis comes from playing the game with God’s rules and still coming out on top.

2 comments