When I was a kid, I could have sworn that wells were going to be a much bigger problem in life. Whether it was the creepy girl popping out of a well in The Ring to the old trope of Lassie barking to the townsfolks about Timmy being trapped in a well (which never actually happened!), the unknown of that deep, dark water hole seemed to be a pressing concern. Now, as a certified adult, I can proudly report that I have yet to actually fall down a well.

When I was a kid, I could have sworn that wells were going to be a much bigger problem in life. Whether it was the creepy girl popping out of a well in The Ring to the old trope of Lassie barking to the townsfolks about Timmy being trapped in a well (which never actually happened!), the unknown of that deep, dark water hole seemed to be a pressing concern. Now, as a certified adult, I can proudly report that I have yet to actually fall down a well.

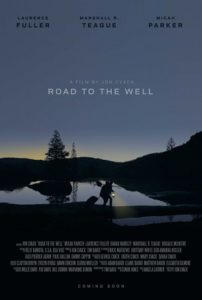

Road to the Well, a film by Jon Cvack, thankfully doesn’t add to the multitude of well-centric entertainment. My younger self can relax. Instead we find something far deeper and darker waiting for our characters to stumble into. A trippy who-dun-it wrapped in a buddy road trip, Road to the Well is a film about the choices we make and whether or not they condemn us.

The journey follows Frank and Jack, old friends who are casually reunited as the film begins. Jack is a drifter with a questionable background, and Frank is an office paper pusher, clearly wanting more from his life. A night of drinks and loose decisions leads to a murder victim in Frank’s trunk and begins a descent into darkness for the two men. For Jack, it seems all too familiar, his cool not even broken over a corpse. Frank, though, is a mess of hesitancy. They quickly become each other’s yin and yang. Chaos and calm, reaction and reason.

The film seems to purposefully shove the despicable in our face. Dialogue is sometimes relentlessly blunt, many outer lying characters are unlikable at best and vile at worst. This serves to reinforce the macabre of the path but does lack some balance. Still, these characters are landmarks along the road, pillars of the choices they have made. Frank’s girlfriend is cheating on him with his boss. Their friend Chris is engaged to be married yet struggles with being unfaithful. Every choice is made to seem lasting, making Frank’s journey all the more urgent.

Road to the Well examines faith as much as choice. We hit it head on with in the film’s most powerful scene as the two men meet a military veteran, Dale, who is on to their scheme. He explains that he is a man who has lost his faith, and wants to end his life. Still, he cannot deny his own moral conscience enough to go through with it himself. This is the essence of the film’s struggle. It is a standoff between belief and action. Jack is all action. Frank is unable to act. But we see that he cannot escape inevitability, and must act anyway. The central question is will Frank become what Jack is dragging him to be, or take control of his own decisions?

Road to the Well examines faith as much as choice. We hit it head on with in the film’s most powerful scene as the two men meet a military veteran, Dale, who is on to their scheme. He explains that he is a man who has lost his faith, and wants to end his life. Still, he cannot deny his own moral conscience enough to go through with it himself. This is the essence of the film’s struggle. It is a standoff between belief and action. Jack is all action. Frank is unable to act. But we see that he cannot escape inevitability, and must act anyway. The central question is will Frank become what Jack is dragging him to be, or take control of his own decisions?

Ultimately the story lands on solid ground. Road to the Well is an impressive feat for an independent film. From the cinematography to the directing, the editing and especially the acting, you are never drawn out of the story by the production. Actor Micah Parker exudes the patient charisma of Oscar Isaac. He plays Jack with just the right amount of simmering edge. Laurence Fuller wears the surrendered melancholy of Frank like a comfort blanket tattered with holes, ready to snap at any moment. The landscape of the film is often visually stunning, grim when it needs to be and striking when you least expect it.

The fears of childhood are often grandiose, aren’t they? Quicksand and wells, cartoonish bad guys and alien invasions. Life is far subtler. The wells we must avoid tumbling down are far less obvious. Such is the picture painted by Road to the Well. In it we can see the role of faith as the only thing that provides hope. For the Christian, faith is our evidence that the choices we make do not eternally condemn us. We believe the price has been paid. And that is an extraordinarily powerful thing to consider when you are looking upward from the bottom of a well.