The Redeeming Culture Cinephile is our new series about classic films; we hope you enjoy this first look at some of the formative films in cinema history.

This dreamlike parable of a movie wasn’t an instant classic. Many people don’t think it’s at all exceptional the first time they watch it; but it grows on the mind, and usually the next time they catch it, it becomes great, much as in the decades following its inauspicious release, The Night of the Hunter so grew in esteem that it is now difficult to find longer lists of the best movies ever made which do not include it.

Its dreamy qualities are intentional, clear from the very beginning, and throughout, via the music and lyrics. And it has some of the most dynamic black and white cinematography ever committed to film.

The director, Charles Laughton—much more known for his outstanding performances—partnered closely with the cinematographer, as well as the editor and composer, both of whom were on set during the filming, leading to a movie whose artistry is comprehensive.

The Plot (a.k.a. Spoilers)

Harry Powell, a man who passes himself off as a traveling preacher, finds out that his cell mate had left stolen money with his family, rather than returning it. On his release, Harry travels to the man’s hometown to find his widow, Willa. He convinces the town that he is a true man of God, and marries her. When Willa won’t tell him where the money was hidden, he kills her. He realizes that the money had been hidden with the children, John and Pearl; so he tries to cajole, then threaten them, into revealing it. They run to John’s friend, Bertie, an old man who takes care of a little dock, and they flee on a boat with Harry in pursuit on land. They wind up in the care of an older lady named Rachel, who already raises three other orphans. Harry eventually turns up and tries to get to the kids, but Rachel is too bright for him. He is captured by the police, never having found the money hidden in Pearl’s doll, and the kids stay with Rachel, finally fully safe, in her good hands.

In the Hands of Men

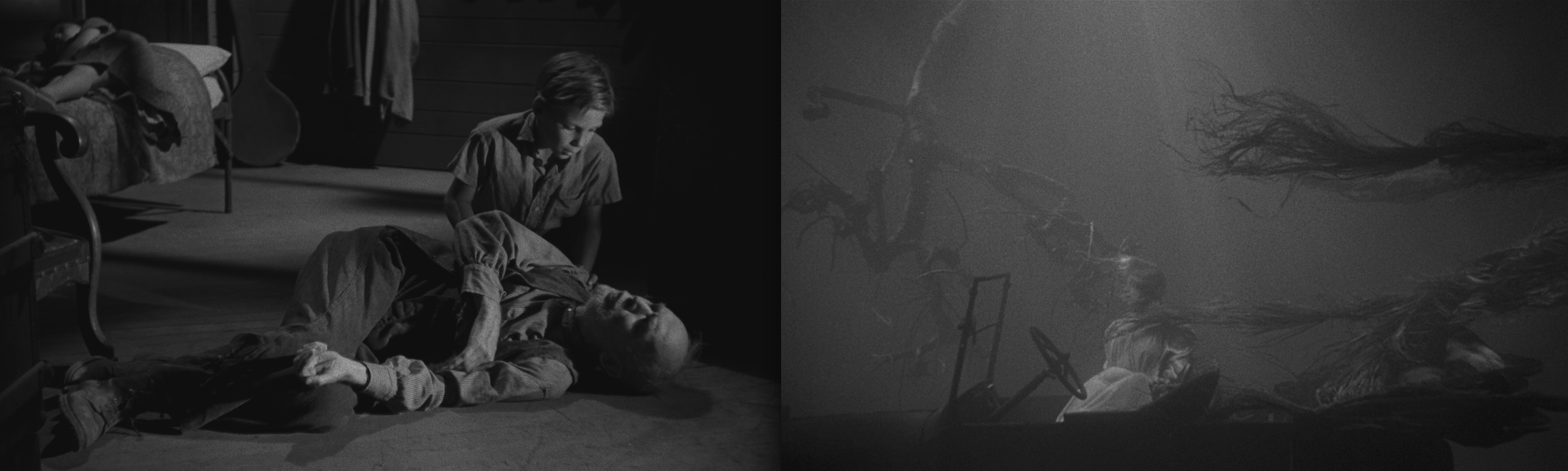

As a whole, the movie is surprisingly reflective of Christian views of the world, evident in even more ways than I will note below. It comes in three distinct sections. In the first, John and Pearl are in the hands of men. I mean that in this negative context:

…Jesus would not entrust himself to them, for he knew all people. He did not need any testimony about mankind, for he knew what was in each person.

–John 2:24-25, NIV

All of the adults in their community are unreliable. Their mother is depressive, and while not altogether dumb, she’s also not bright enough to be an effective guardian. The Spoon couple, who stand in for the town as a whole, are clueless. Even Bertie, having committed to being there for John any time, when he is needed, he is falling down drunk.

It’s for a valid reason; he’s overcome with shock from seeing Willa’s dead body in the waters around which he works. Nevertheless, when John needs him, he has disabled himself too much to do any good. In the world of the ingenuinely godly, these kids are on their own.

Stylistically, this first part the movie is it akin to the kinds of dreams that come at the beginning of the night: a bit broken, sometimes changing tones abruptly. It may seem like clunky filmmaking, lurching from the pastoral to the alarming, but as the rest of the movie plays out, those things which might seem too comic or direct reveal themselves as deliberate, not mistakes.

In the Hands of God

In the second section of the movie, we have children in the hands of God. As they flee Harry, they must drift down river wherever it takes them. Later, they will be directly compared with Moses. They can do little more along the way than stop, hoping for an evening’s shelter, which they find in a barn. They are reluctantly fed by strangers, like the man in Jesus’s parable who sought bread and got it, not because his neighbor was good, but because he’d bothered him.

This part resembles elegant dreams from the middles of nights, those I remember most fondly when I wake up, the beautiful dreams, loaded with emotions. Here, the film lives inside a nurturing song.

In the Hands of His Body

The final section puts the children in the hands of a real person of God. This part most resembles dreams from the end of a night’s sleep: more grounded, more realistic. When Rachel shows up, she is a breath of fresh air, clearly an admirable woman of great sense and sharp intuition. While it still has a few stylistic flourishes, the film’s generally increased realism matches the presence of her character.

Laughton did not set out to make a movie that reflects Christianity, but he also wasn’t making a movie designed to bash God, or even Christianity as a whole. He knew religions could be used for bad ends by wicked people. This is established when the warning about wolves in sheeps’ clothing is given. Harry is not a Christian.

His right-hand-left-hand sermon is the vaguest nonsensical hokum. In the book, he frequently refers to Jesus by name; but in the movie he does not, a deliberate choice made by Laughton. This stands out strongest when he is outside Rachel’s house, waiting for all to fall asleep so he can come in and take the children, while she stands guard on her porch with her shotgun. He sings “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms,” referring to the Lord only by designation. She joins in with him, backing up his singing with “leaning on Jesus.” She does say His name.

This mattered to Laughton. It reflected her authentic relationship with God, compared with Harry’s inauthentic, culturally faked one. She’s what the movie has been leading to. She is the contrast to Harry Powell’s false Christianity. She’s the real deal.

It’s too easy to dishonestly portray Christianity by only showing the Harry Powells, and for Laughton, Harry was a strongly representative figure of us and our religion, but he was also honest enough to show a real Christian, letting his accusations fall only where they belonged, rather than leaving the results of a too-broad brush.

• • •

Thanks for reading. The Redeeming Culture Cinephile seeks to examine the classics of film history through a culture-redeeming lens. Read more reviews of classic flims here.

1 comment