Look at them. They’ve never met anyone like you before, that granite face, wisdom and integrity etched into every line. The eloquence, the conviction…they don’t know what hit them.

—Dr. Altan Inigo Soong

Soong’s criticizadmiration of Picard might as well have been the pitch for Star Trek: Picard, and as it turns out, we’ve needed every minute of it. What started out as a tough year has pivoted into a global crisis, and if ever we needed the strong, wise, honest, eloquent, passionate voice of Jean-Luc Picard, it’s now.

Soong’s criticizadmiration of Picard might as well have been the pitch for Star Trek: Picard, and as it turns out, we’ve needed every minute of it. What started out as a tough year has pivoted into a global crisis, and if ever we needed the strong, wise, honest, eloquent, passionate voice of Jean-Luc Picard, it’s now.

But as particular as early 2020 might be, that sentence will always be true: we need that voice. We need his words of wisdom and conviction. We need that certainty. And seeing Jean-Luc get that back, seeing him rise up from his failure and become the Captain we all remember again, has been a particular thrill. Cathartic, even, on a surprising level. Truly, I don’t know what hit me.

Now we’re here, though; and in the first part of the season finale, we get the season’s thesis writ large across the narrative. It’s been the question of Picard’s life since the Romulan rescue, a Kobayashi Maru with dire consequences. What if he can’t save these people—again? Soong even brings it up in an attempt to prod old insecurities: what if nobody will listen to him? But the big question itself is actually spoken by Soji, as she tries to make sense of Jurati’s actions a few episodes ago.

Soji: I guess I’m just trying to understand the logic of sacrifice.

Picard: “The logic of sacrifice?” Hmm…I don’t like the sound of that.

Soji: So you think there is no logic? No calculus of life and death?

Picard: I think it depends on if you’re the person holding the knife.

The Girl with the Enamel Eyes

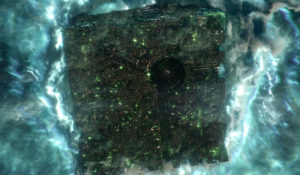

“Et In Arcadia Ego” is packed to the synthetic gills with symbolism. The title refers to a 17th-century Baroque painting and means “even in paradise, death is there;” the orchids which disable the battling starships over the synth’s home planet of Ghulion IV represent purity and perfection defeating fallible organics; the names of the synths in the settlement are all tightly-wound with meaning and reference.

“Et In Arcadia Ego” is packed to the synthetic gills with symbolism. The title refers to a 17th-century Baroque painting and means “even in paradise, death is there;” the orchids which disable the battling starships over the synth’s home planet of Ghulion IV represent purity and perfection defeating fallible organics; the names of the synths in the settlement are all tightly-wound with meaning and reference.

But perhaps the most obscure reference is the name of the settlement itself: Coppelius Station. The location takes its name from a mad scientist in the 19th-century French ballet Coppélia: The Girl with the Enamel Eyes. In it, Dr. Coppélius builds a room full of life-sized dancing dolls, including a particularly lifelike and beautiful one named Coppélia. When local boy Franz falls in love with the doll, the mad scientist decides to sacrifice Franz in order to bring Coppélia to life.

Taking a life for the sake of another.

This isn’t far-fetched at all, and it’s not science fiction. We talk about it all the time in philosophical problems like the Trolley Problem; we make decisions while driving that could end up harming others; we must decide between our comfort and the good of others. As quarantine and self-isolation continue, it’s even come up in discussions about how long we leave our economy on hold. It’s rarely so direct and immediate for us; usually our decisions and the consequences aren’t immediately connected.

This isn’t far-fetched at all, and it’s not science fiction. We talk about it all the time in philosophical problems like the Trolley Problem; we make decisions while driving that could end up harming others; we must decide between our comfort and the good of others. As quarantine and self-isolation continue, it’s even come up in discussions about how long we leave our economy on hold. It’s rarely so direct and immediate for us; usually our decisions and the consequences aren’t immediately connected.

For Soong, as well as Soji, Sutra, and the rest of the dancing dolls at Coppelius Station, the question is existential: 218 Romulan Warbirds are coming to “rain fire” on the planet, and they must either try to survive and live a life on the run, or use the Admonition to end the organic life that brought them into being.

Live in fear? Or sacrifice others so that the doll may live?

Fear and the Logic of Sacrifice

These decisions, as Picard notes, are only easy when you’re the one “holding the knife.” And when your own survival depends on killing someone else…the words of fear make it feel like it’s the only option.

Picard: Did she think she was right? Or did she simply believe she had no choice?

[…]

Soji: Maybe there’s no logic in it at all. Maybe all rationales for killing just boil down to fear—the opposite of logic. But what if killing is the only way to survive?

The Admonition—and the higher synthetic power who sent it, as well as its representative at Coppelius Station, Sutra—inject fear into the minds of those who hear it, promising that there is no way to survive without bloodshed. To organics, it speaks only madness. But to synthetics, the Admonishers say, “you will die unless we save you; and the only price is to sacrifice those who made you.”

The Admonition—and the higher synthetic power who sent it, as well as its representative at Coppelius Station, Sutra—inject fear into the minds of those who hear it, promising that there is no way to survive without bloodshed. To organics, it speaks only madness. But to synthetics, the Admonishers say, “you will die unless we save you; and the only price is to sacrifice those who made you.”

Words of fear do a booming business, and it overtakes our minds in ways subtle and gross. We make decisions for ourselves and our families, sacrificing the needs of others. We try to figure out ways to use other people for our benefit. We all become desperate for some semblance of control.

It’s easy to see in a crisis, when empty toilet paper aisles can attest to the brain-breaking power of fear; but what about in times of plenty or calm? It’s not like fear isn’t present then, too; it’s just more abstract. Our fallen nature tells us, “you will die unless you give into fear; and the only price is to sacrifice everyone but yourself.”

And when the words of fear break in, we don’t listen to the words of our Creator. We don’t hear the truth He exudes with His very being. We ignore His reassurances of peace and protection. Back in the Garden of Eden, it was listening to the words of fear—that God was holding out on us—that caused sin in the first place.

So it has been ever since, the words of fear pushing out the words of God, making us sacrifice others. What we need are words of hope.

Hope and the Calculus of Life

Hope and the odds make poor bedfellows.

—Jean-Luc Picard

It’s interesting to me what a beacon of hope Raffi has been in this season; she’s supposed to be the paranoid one, the woman who sees Romulans around every corner, the one who warns of homicidal fungi and angry reptiloids. She doesn’t believe that anyone could’ve survived the crash of the Artifact. But she’s also been a driving force behind getting both Jurati and Rios back on their feet after crippling despair. She even gives Picard a nudge here and there. She’s the anti-Sutra, spreading hope instead of fear.

It’s interesting to me what a beacon of hope Raffi has been in this season; she’s supposed to be the paranoid one, the woman who sees Romulans around every corner, the one who warns of homicidal fungi and angry reptiloids. She doesn’t believe that anyone could’ve survived the crash of the Artifact. But she’s also been a driving force behind getting both Jurati and Rios back on their feet after crippling despair. She even gives Picard a nudge here and there. She’s the anti-Sutra, spreading hope instead of fear.

I’ve been trying to figure out how she’s done this; how such a person could be both extremes at once, and the only answer I can come up with is in the nature of hope itself: it’s not something we can excite in our own hearts, it has to come from outside. Like words of fear poison our hearts, words of truth and love can bring hope; and Jean-Luc Picard is a prime exporter of truth in the Federation.

Raffi spends enough time around Picard that her heart is full of truth and words of hope; and even though she goes through hard times, those words of hope are what come out when people need her help.

There is no fear in love, but perfect love casts out fear.

—1 John 4:18, ESV

In our hearts, that hope also blasts away the fear that drives us to hurt others. Words of hope refute the words of fear that make us care only about ourselves.

In our hearts, that hope also blasts away the fear that drives us to hurt others. Words of hope refute the words of fear that make us care only about ourselves.

That doesn’t mean there’s no place for sacrifice. Indeed, for us to have hope at all, we need sacrifice; our hope comes at the hands of another. But while we benefit from the sacrifice, Jesus holds the knife that takes His own life; and when He bleeds, truth comes out.

Because, while the Admonishers speak words of death and fear to sentient synths, God speaks words of life and hope. While they call the mad scientist’s dancing dolls to take their life at knifepoint, Jesus sacrificed Himself to save others. And like Raffi and JL, when you spend enough time around His truth, it fills you up.