The streets are music and the stars are made of fireworks; the coffee isn’t coffee but it’s love con leche, and sueñitos of the peoples in these ordinary places come alive in Washington Heights. You just have to see the barrio through the right eyes.

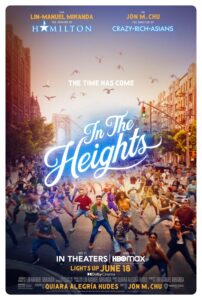

In Jon Chu and Lin-Manuel Miranda’s long-awaited big-screen adaptation of Miranda’s Broadway staple, we get that chance. Life’s not perfect In the Heights—in fact, it’s pretty tough—but somewhere between the piragua guy and the beauty salon, you get to see a world that most people don’t have a chance to experience.

In Jon Chu and Lin-Manuel Miranda’s long-awaited big-screen adaptation of Miranda’s Broadway staple, we get that chance. Life’s not perfect In the Heights—in fact, it’s pretty tough—but somewhere between the piragua guy and the beauty salon, you get to see a world that most people don’t have a chance to experience.

It’s a beautiful film and a captivating story, well-told and well-performed. But for me, what the big-screen version of the musical offers is a look at the world through different eyes: those of the Latinidad, Latin Americans cast far and wide by an economic diaspora, creating communities where they landed. Like Usnavi sees beauty in the world through Vanessa’s eyes, I had an opportunity to see and seek the beauty of community through the eyes of the Latin Diaspora. And even though I’m not fleeing turmoil, maybe I can take from them some lessons for my own diaspora community.

Spoiler alert: plot and ending spoilers for In The Heights follow.

Our neighbors started packin’ up and pickin’ up and ever since the rents went up

It’s gotten mad expensive, but we live with just enough

—Usnavi

Jon Chu’s lavish shot composition and the cast’s breathtakingly-aerobic choreography bely the deep struggle of keeping the diaspora community of Washington Heights together. The twin contradictions of gentrification and poverty have pushed Daniela and her salon out of its longtime location to another neighborhood, forced Kevin to sell his car service piece-by-piece to send his daughter to college, and perhaps worst of all, driven Usnavi himself to leave his bodega behind in hopes of recapturing his father’s dream of a cantina on the Dominican beach.

With these anchors removed, the tightly-knit community is unraveling; Nina is unmoored from an extended family she’s sure that she has let down, Vanessa is desperate to leave the barrio in search of a career she doesn’t think possible in her apartment by the railroad tracks, and Sonny is frantically hiding his desperate secret even as he tries to escape his past.

Only Abuela can keep this vibrant community together, but she’s dying. And the Heights, as Usnavi spells out at the beginning of the story, are dying with her.

Only Abuela can keep this vibrant community together, but she’s dying. And the Heights, as Usnavi spells out at the beginning of the story, are dying with her.

There’s no getting around it: maintaining a community of disparate and diverse people is hard. Even if you’re as good at being together as the people of Washington Heights, those you gather around you will eventually be pulled away; by money problems, by job stresses, by pandemic and illness, family and tragedy, success and hardship. Keeping people together is complicated, requiring a deep and abiding love that seeks the best of others and dares to keep on loving even in that brokenness. This movie embraces that difficulty with eyes wide open. But the people of the barrio also show me that it’s worth the effort. “We came to work and to live and we got a lot in common,” Usnavi says, and then they prove it.

When Abuela passes, their shared grief brings the entire community together in alabanza—praise—to who Abuela Claudia was and what she did for all of them, raising her up to God’s face. You can see in Usnavi’s eyes how the pain threatens to overwhelm him; but the people all around bind him up. That sort of support in hardship buoys Nina, Vanessa, Sonny, and Kevin, too; as those around them willingly and joyfully sacrifice to be a blessing to one another. And as they overcome their shared difficulty of powerlessness on a scorching day, they come together in one of the most exultant and life-affirming numbers of the film, Carnaval del Barrio; temporarily laying down their burdens and living loudly in a way that staves off the realities of the world just long enough to survive together.

That’s what a healthy community looks like. Not perfection, a bending-in toward each other in imperfection, and a reaction to hardship that puts others first—because when you need help, they’ll do the same for you. When Christ tells His church “by this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you love one another,” that’s what He means.

Yeah, I’m a streetlight, chillin’ in the heat!

I illuminate the stories of the people in the street

Some have happy endings, some are bittersweet

But I know them all and that’s what makes my life complete

—Usnavi

In The Heights follows in a grand tradition of movies (Chu’s own Crazy Rich Asians had a similar effect on me) that drop me into a real place, which real people in the real world consider perfectly normal, and makes that place seems as fantastical as Middle-Earth or a galaxy far, far away: as a white man in the midwestern US, the overwhelming world within the barrio of Washington Heights was breathtaking to behold.

In The Heights follows in a grand tradition of movies (Chu’s own Crazy Rich Asians had a similar effect on me) that drop me into a real place, which real people in the real world consider perfectly normal, and makes that place seems as fantastical as Middle-Earth or a galaxy far, far away: as a white man in the midwestern US, the overwhelming world within the barrio of Washington Heights was breathtaking to behold.

That said, the world is also undeniably grounded by the people who inhabit it; fully realized characters assert their dignity through little details from lights up to the cool breezes that flow. Real people with real problems, real loves, and real desires; but real people who deserve a dignity that the world is hesitant to give them.

I don’t see myself demographically in the characters of this film. But I do see myself in the “little details that tell the world we are not invisible.” Usnavi, Nina, Vanessa, Benny, Sonny, Abuela Claudia, Kevin, Daniela, Carla, even the piraguero—whether they are singing, dancing, thinking, making, telling, doing, or sweeping someone off their feet, these people display their dignity with a spotlight, shining brightly the fact that they aren’t beholden to the way I expect them to act in their difficulty and hardship.

They all want to prove that they have value and worth. We all do. That’s part of who we are as humanity; God made us to wrestle the Earth into submission, to make our mark on the planet. And He saw that it was very good.

But He also gave us inherent worth and value by making us in His image.

But He also gave us inherent worth and value by making us in His image.

It’s a remarkable contrast: on one hand we have a people rightly asserting the detailed dignity of defiant delight. But on the other, we have a God who says “you don’t need to assert any of that just to be worthwhile. You have dignity inherently, just because I made you.”

This allows us to use that assertion of dignity to connect with the God who made us desire it and gave it to us. But it also allows us to be free with our love and care, lavish with our affection, and heedless in our pursuit of one another’s welfare.

It allows us to seek the good of the world around us, hoping and working for a world that embodies that ideal.

“Maybe Stanford isn’t a way out. Maybe it’s a way back. Like Abuela always used to say, ‘asserting our dignity in small ways.’”

“Wow. This is it, huh, mija?”

“What?”

“This is the moment when you do better than me. Not because of some fancy degree, it’s because you can see a future that I can’t.”

—Nina and Kevin

I don’t know about you, but I can’t just do that. That beautiful community is alluring, even enchanting, but the ideal of a healthy community isn’t enough motivation to do what needs to be done. Or maybe it will be for a while, just not forever. There needs to be more than just stars in our eyes and fireworks in the sky. Usnavi and Nina both deal with that deficit in their own hearts, too.

While Usnavi clearly loves Washington Heights from the start of the film (and at least one person in particular who lives there), that ideal isn’t enough; he needs a motivation to push him over the edge, which finally comes when he truly sees the Heights through Vanessa’s eyes. It’s the people of the barrio that keep him grounded, that give him a purpose and a drive to stay; to preserve what he can of the community, even if the stories of those who left increase while his café con leche customers decrease. His community—not a shiny ideal, but his actual people—becomes his sueñito and his reason to stay.

And the very same thing becomes Nina’s reason to go. When she didn’t have the strength to go back for herself, when she didn’t even have the strength to face the racism and animosity there to make her community proud, her courage coalesced around helping her people by acquiring the skills at Stanford to assert Washington Heights’ dignity. It’s the people of the barrio that send her away—not in anger, as she feared, but in hope that she can raise their fortunes when she returns, that she can help save Sonny and those like him from losing what little they have to an indifferent system.

It got me thinking about my motivation to do what I’m called to. My family is a great one; but the world is bigger than us, and when I need a reminder to “seek the welfare of the city,” as Jeremiah 29 says, the love Usnavi and Nina show the people of Washington Heights by staying and going reminds me that the stories of others and the welfare of God’s people is more than enough reason, more than enough of a push, a greater motivation than the mere idea of what I will do or the shiny world I may never see. I’m going to lift them to God’s face and plead with Him to bless what I do.

Christians are a people of diaspora, scattered by sin and driven to the ends of the Earth. As we long for a greater homeland than even a Dominican beach, we have a responsibility to the community we’ve joined here. In the diaspora community of In the Heights, we see a diaspora that faces even more hardship and trouble than most of us face; and in their joining together, in their joy, in their dignity, we see a powerful way to live together.

Christians are a people of diaspora, scattered by sin and driven to the ends of the Earth. As we long for a greater homeland than even a Dominican beach, we have a responsibility to the community we’ve joined here. In the diaspora community of In the Heights, we see a diaspora that faces even more hardship and trouble than most of us face; and in their joining together, in their joy, in their dignity, we see a powerful way to live together.

I can help these people; cancel my flight, I’m staying.