There is something strangely poetic about watching a horror documentary while laying in a chair having plasma separated from one’s own blood. It makes it doubly poetic watching a documentary about the history of African Americans in horror film. Blood, itself, becomes a complex subject within historical concerns about race: the “one drop” rule that became codified in some states during the 20th century stated that one drop of blood of sub-Saharan African descent made a person black, thereby placing them in a racial caste within a “caste-less” society. It didn’t matter what the percentages of ancestry were, the majority powers (read: white Europeans) placed the individuals into the lowest class available. And this is only one aspect of America’s long history of constructing a social, cultural, economic, legal, and political system that is, essentially, rigged to sustain the power base of the majority. One of the central connective tissues of biological life is splintered into endless ambiguities that alienate.

There is something strangely poetic about watching a horror documentary while laying in a chair having plasma separated from one’s own blood. It makes it doubly poetic watching a documentary about the history of African Americans in horror film. Blood, itself, becomes a complex subject within historical concerns about race: the “one drop” rule that became codified in some states during the 20th century stated that one drop of blood of sub-Saharan African descent made a person black, thereby placing them in a racial caste within a “caste-less” society. It didn’t matter what the percentages of ancestry were, the majority powers (read: white Europeans) placed the individuals into the lowest class available. And this is only one aspect of America’s long history of constructing a social, cultural, economic, legal, and political system that is, essentially, rigged to sustain the power base of the majority. One of the central connective tissues of biological life is splintered into endless ambiguities that alienate.

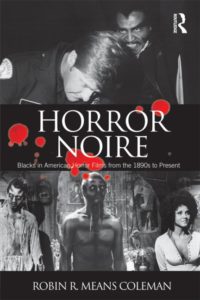

I first read Robin R. Means Coleman’s Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to Present three or four years back and it has stood as quintessential reading for any horror writer, critic, academic, or mere fan. For one, it stands as the only substantial work that articulates one of the most hidden original sins of horror cinema: the obscuring and dehumanizing of minority peoples—significantly African Americans—throughout its history. For another, it represents what the best academic works are wont to do: make gray what is thought by the populace to be black and white (no pun intended). Coleman’s love of the horror genre emanates from each page, and she wrestles, like so many other other people of color, with a love that is unrequited. At the time I read it, I had begun to see the shape (however darkly) of how deep white European hatred of dark skin went. Horror Noire showed me that this hatred was cooked into the genre from the very beginning. A stark revelation, to be sure.

I first read Robin R. Means Coleman’s Horror Noire: Blacks in American Horror Films from the 1890s to Present three or four years back and it has stood as quintessential reading for any horror writer, critic, academic, or mere fan. For one, it stands as the only substantial work that articulates one of the most hidden original sins of horror cinema: the obscuring and dehumanizing of minority peoples—significantly African Americans—throughout its history. For another, it represents what the best academic works are wont to do: make gray what is thought by the populace to be black and white (no pun intended). Coleman’s love of the horror genre emanates from each page, and she wrestles, like so many other other people of color, with a love that is unrequited. At the time I read it, I had begun to see the shape (however darkly) of how deep white European hatred of dark skin went. Horror Noire showed me that this hatred was cooked into the genre from the very beginning. A stark revelation, to be sure.

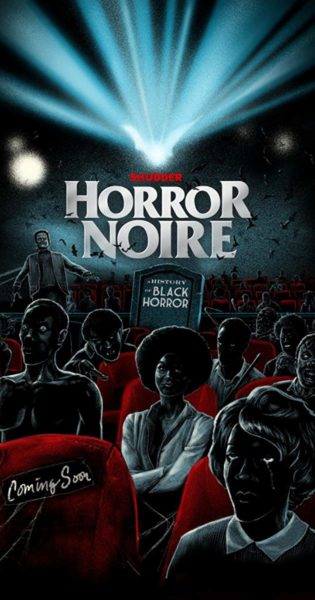

Late last year when I heard that this book was finally going to receive a sliver of the recognition it deserves by being made into a documentary for Shudder, I put this review on the calendar at Reel World Theology. I am so happy to announce that the resulting product did not disappoint. How could it? Coleman, Tananarive Due, and Ashlee Blackwell—from Graveyardshiftsisters.com—were behind it. Black women speaking truth to power. I only wish the documentary could have been longer in order to incorporate the deft nuance that ran throughout Coleman’s book. As it stands, the documentary makes for a solid Reader’s Digest version of the book: gets in, hits the basic themes and arguments, gets out. I only hope peoples’ experiences with this documentary invite a spike in sales for Coleman.

“A man has got to be able to see his face.”

– Blacula (1972)

If one wanted to try to sum up the central argument of Horror Noire—in both mediums—it would be that during a large portion of horror cinema history, black people were largely invisible in horror even when they were characters, portrayed by white people in blackface. When they actually starred in these films, they were made monstrous (The Creature from the Black Lagoon, King Kong), servants—magical or sacrificial—to the lives and existential goals of white characters (The Shining, The Serpent & The Rainbow), or they were the whitewashed buffoons afraid of their own shadows (most films of the first 30-40 years of horror). As the documentary points out, when these representations are the majority and they have saturated the cultural landscape so significantly, the films and periods that were exceptions stick out so clearly.

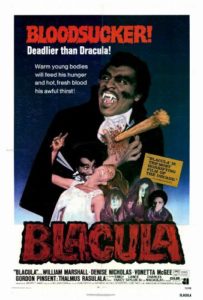

The earliest examples were Spencer Williams’ films during the 30s and 40s which sought to combat the image of the black community by making moralistic films that told black people to act and dress a certain way so that they could be blameless in the eyes of whites. Powerful in their own way, these films congregated all-black casts and gave black people their first real representation. This would be the most significant visibility of African Americans in horror until Blacula in the 70s when the classic vampire tale was re-envisioned within the black gaze. The follow up, Scream Blacula Scream, continued the model; however, studios owned by whites picked up on the popularity of these films and exploited them by making what we call “blaxploitation” films now. Largely made by white people with black actors and actresses, a majority ended up re-instituting the black cultural stereotypes of the day. Only the occasional film found its way out of this pattern and they all had something in common: black directors and/or writers.

The earliest examples were Spencer Williams’ films during the 30s and 40s which sought to combat the image of the black community by making moralistic films that told black people to act and dress a certain way so that they could be blameless in the eyes of whites. Powerful in their own way, these films congregated all-black casts and gave black people their first real representation. This would be the most significant visibility of African Americans in horror until Blacula in the 70s when the classic vampire tale was re-envisioned within the black gaze. The follow up, Scream Blacula Scream, continued the model; however, studios owned by whites picked up on the popularity of these films and exploited them by making what we call “blaxploitation” films now. Largely made by white people with black actors and actresses, a majority ended up re-instituting the black cultural stereotypes of the day. Only the occasional film found its way out of this pattern and they all had something in common: black directors and/or writers.

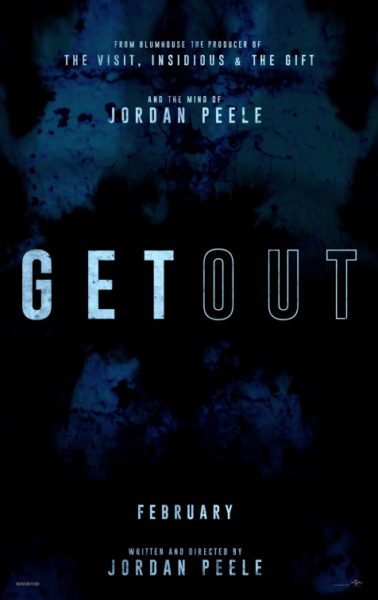

They became invisible once again in the 80s; or they were present, but killed in order to save the white final girl—a term developed by Carol Clover. It wasn’t until the 90s and 2000s with the increasing popularity of hip-hop culture that African Americans were able to slowly begin to repaint their image in horror as self-possessed survivors who were morally complex human beings with their own goals and desires. The documentary makes the case that Get Out (2017) became a fulcrum point for black representation in horror film. This is the only aspect of the documentary that transcends the argument of the book which existed before Jordan Peele’s instant classic came into existence.

We see finally one of the few black nightmares brought to the screen. The fear of African Americans in all-white spaces with the full weight of American—and world—history hanging in the air. Peele sought to make a film that not only avoided all of the pitfalls of horror up to that point, but reveal and subvert the original sins of American horror film. There are no good white people in Get Out. That is the fear that the black community has to live with day in and day out in our current society. Get Out pegged that fear perfectly. It’s presence made a perfect concluding note for the documentary. I can only hope that a new edition of Coleman’s book is released with a new chapter on black representation in the 2010s. The tides are turning, but the fear of invisibility still stands as the black community moves into the 2020s.

We see finally one of the few black nightmares brought to the screen. The fear of African Americans in all-white spaces with the full weight of American—and world—history hanging in the air. Peele sought to make a film that not only avoided all of the pitfalls of horror up to that point, but reveal and subvert the original sins of American horror film. There are no good white people in Get Out. That is the fear that the black community has to live with day in and day out in our current society. Get Out pegged that fear perfectly. It’s presence made a perfect concluding note for the documentary. I can only hope that a new edition of Coleman’s book is released with a new chapter on black representation in the 2010s. The tides are turning, but the fear of invisibility still stands as the black community moves into the 2020s.

What the documentary illuminates so well about the academic work of Coleman is how horror presents itself as a mirror of society. It’s not hard to see how the King Kongs and Black Lagoon creatures are just a small skip from the dehumanizing depictions of black people in early American publications. Or how the representation of black people throughout most of cinematic history has attempted to keep the black community in a form of slavery to white desires or monetary ventures. The history of the horror genre parallels the history of African American history. Coleman essentially provides a documented analysis of the genre that echoes Pam Noles’ 2006 essay, “Shame,” where she recounts her own wrestling with fantasy, science fiction, and horror as a young black girl. She concludes:

If I haven’t “left these people after all this time,” my Mom said, then what I need to do is accept that I’m stuck with the way things are. I can look at this current world of genre and keep whining, or I can take note of the positive changes that have come down over the years and hope that more will come in the future. And if it matters that much to me, I’ve got to figure out what I need to do to bring that future into being rather than just waiting for it to magically appear. What those actions are, she can’t say. That I’m trying to figure it out pleases her in a way, even though “when it comes down to it, you’re still talking about that weird stuff.” But since it’s this weird world I’ve chosen, she’s glad I’m trying to make it my own.

Dad’s advice was cryptic only if you fail to understand that he knows precisely what it means to look directly into the face of what you love while saying you are wrong.

Coleman does her part in both her book and with this new documentary which is deeply indebted to her work. This is information that needs to be consumed and wrestled with honestly. Even more so for white Christians, like myself, who know the deceit and lies that the powers and principalities utilizes to separate us from each other and from our Maker. I, for one, will do my best to make Coleman’s work known and now the documentary makes this work a bit easier. Thank you, Coleman and Shudder, for shining a light on a cultural history that is difficult to confront, yet ever so important.

1 comment