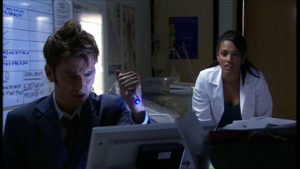

In this second episode of the new season, the Doctor finds himself in a hospital that is displaced to the moon by the Judoon. These rhino-looking alien creatures are “police for hire” who have taken the hospital to “neutral territory” in order to find and punish a fugitive criminal. They systematically search the hospital, scanning each terrified person to determine their race in order to locate the non-human they seek.

In this second episode of the new season, the Doctor finds himself in a hospital that is displaced to the moon by the Judoon. These rhino-looking alien creatures are “police for hire” who have taken the hospital to “neutral territory” in order to find and punish a fugitive criminal. They systematically search the hospital, scanning each terrified person to determine their race in order to locate the non-human they seek.

We quickly discover that an old lady in the hospital—Florence Finnegan—is not what she seems to be. She is an “internal shape-changer,” according to the Doctor, who is fleeing the law after committing murder. She has chosen her disguise well, taking one of the most unassuming forms imaginable—a sweet, frail old lady. What she really is could not be of higher contrast: selfish, vindictive, strong, cruel. In order to hide from the Judoon scanners, “Mrs. Finnegan” must drink human blood in order to register as human, a process that kills her victim and something she has no qualms about doing.

Though we may wish it to be a rather drastic comparison, Mrs. Finnegan’s behavior is not uncommon to the human experience. We are adept at hiding our true nature, often by any means necessary. We carefully craft masks to hide our true, complicated nature. These visages vary—we may want to appear strong and intelligent, or humble and compassionate; known as the best wife and friend, dependent and loyal, or a lone wolf, untethered and transient. Regardless of the flavor, we don these masks to define and protect us, shaping people’s perception of us and hiding what we do not want others to see.

The admirable qualities we project are a part of us in some way, but there are also parts of our nature that we hate, or that shame us. And though we are good at hiding them, they are always on the verge of being exposed. It takes a lot of time and energy to maintain our facades, a process that is not without personal cost—we hold people at arm’s length, afraid of being found out; we are not fully known, some of our good hidden with the bad; and we close ourselves off to learning and growing when we cannot admit our weaknesses.

The admirable qualities we project are a part of us in some way, but there are also parts of our nature that we hate, or that shame us. And though we are good at hiding them, they are always on the verge of being exposed. It takes a lot of time and energy to maintain our facades, a process that is not without personal cost—we hold people at arm’s length, afraid of being found out; we are not fully known, some of our good hidden with the bad; and we close ourselves off to learning and growing when we cannot admit our weaknesses.

Hiding our sin does not make it go away. It does not protect us or others from experiencing our brokenness. When we are at our worst—our sin nature in full effect—the consequences are real. Things are lost and destroyed and often cannot be repaired. The right response to the destruction our sin causes is justice. Retribution. Payback. As in Mrs. Finnegan’s case, whose actions deserve punishment.

The justice of the Judoon is very black and white. No questions are asked, no contingencies honored. Every human in the hospital during this event is subject to that swift and merciless justice. If they get in the way or are determined accomplices, they are vaporized. The Judoon’s single-mindedness almost causes them to miss Mrs. Finnegan, but the Doctor cleverly goads her into drinking his blood so that she will read “alien” when scanned, thus destroying her disguise. He very nearly dies giving his blood to expose her for what she is. This is reminiscent of the Christian story, in which we have a hero who actually dies in order to expose the true nature of our reality—our inability to save ourselves; our need for a savior. Exposure wasn’t the whole purpose of his coming, though. His plan included grace and compassion as well as justice and judgement.

This is wholly unlike the Judoon mission, for their justice is without nuance or compassion. As soon as Mrs. Finnegan is exposed, she gets what she deserves: death. Isn’t this why we put so much time and energy into hiding ourselves? We are afraid of what will have to die if the unsavory parts of our nature come to light. And yet, when we are guarded, there are losses too. We miss out on authentic relationship and the growth and nearness it brings into our lives.

This is wholly unlike the Judoon mission, for their justice is without nuance or compassion. As soon as Mrs. Finnegan is exposed, she gets what she deserves: death. Isn’t this why we put so much time and energy into hiding ourselves? We are afraid of what will have to die if the unsavory parts of our nature come to light. And yet, when we are guarded, there are losses too. We miss out on authentic relationship and the growth and nearness it brings into our lives.

God is our judge and that is a whole lot of good news for us. In him, justice will be served and things will be made right; but also, because of his love for us, he’s made a way for us to escape the eternal punishment we deserve. He sees our whole selves—not just the masks we wear—and knows our frailty and inadequacy and sin. He knew we could never reach him on our own, but he longed to be with us, near us, in relationship with us. So he sent Jesus to take on our punishment; to be the bridge we cross to get to God. In this way, justice gets what it requires and yet we are rescued from that consequence.

The exposure of self and the grace offered to us go hand in hand. We must come to terms with our whole nature and our need for a savior before God’s incredible gift of love can be fully accepted.

In God, we are seen as completely as we are loved and forgiven. Because of this, we are safe to put aside our masks and be the messy, complicated people that we are.