I’m no stranger to director Alfred Hitchcock’s work, and I have seen Spellbound a few times before this (though it’s been a while), but this movie blew my mind. Not only does it use surrealist ideas and imagery to explore the human mind, but Hitchcock’s commentary on sexism was WAY ahead of his time. Spellbound is such a rich and brilliant film with so much to talk about. I want to discuss Hitchcock’s use of imagery and his brilliant direction, but I mostly want to examine how Spellbound completely flips the man-saves-woman paradigm on its head, which was downright counter-cultural at the time of its 1945 release.

Dr. Constance Petersen (Ingrid Bergman) is a psychiatrist at Green Manors mental asylum. The head of Green Manors is being forced into retirement after a nervous breakdown; when Constance meets his replacement, Dr. Edwards (Gregory Peck), it is love at first sight. Dr. Edwards’s behavior, however, quickly takes a suspicious turn. Constance quickly discovers that he is an imposter; when she confronts him, she discovers that he is suffering from amnesia triggered by trauma and a severe guilt complex. He has no memory of who he is (though they discover his initials are J.B.). He believes he killed Edwards and took his place to cover it up, but Constance knows the human mind–and his mind–well enough to know there is more to the story. By the time the rest of the Green Manors staff discovers that the would-be Edwards is an imposter, J.B. has fled. Constance follows after him, determined to cure him and discover the truth behind Edwards’s death.

After evading the authorities, the pair seeks asylum with Constance’s old mentor and friend, Dr. Brulov (wonderfully played by Michael Chekhov). Dr. Brulov is brilliant and hilarious, and one of my favorite characters in the movie. Constance tells him that she is newly married and that J.B. is her husband. Dr. Brulov sees right through this, of course. When J.B. begins to seem unstable and dangerous, Dr. Brulov threatens to call the authorities. Constance convinces him to give her time and to help her try to cure J.B. When they delve into J.B.’s memory–and his dreams–enough to discover the location of his most recent trauma (witnessing Edwards’s death), Constance insists they reenact the circumstances in order to reveal the entire memory. She is risking her own life to test her theory and betting her life on J.B.’s innocence–for if he did murder Edwards before, he will likely kill Constance in the reenactment.

Constance’s theory proves to be true. J.B. is innocent, and Edwards’s death seems to have been an accident. But once the authorities recover the body, they discover that Edwards had been shot. J.B. is arrested, tried, and convicted of the murder, but Constance refuses to believe he is guilty. When she finally returns to Green Manors, she learns that the murderer was essentially right in front of her the whole time. Her choice to confront the villain directly seems, at first glance, like a foolish mistake or some sort of misplaced professional courtesy–the murderer even calls her a fool. But as Constance talks him down while he points a gun at her, she demonstrates that she understands his mind and how it works well enough to know that he won’t shoot her. She uses her superb (and superior) intelligence to talk her way out of her situation. As soon as she leaves the room, the villain turns the gun on himself.

Hitchcock is known as “the master of suspense,” and the title is well earned in Spellbound–especially when he keeps putting sharp objects in front of unstable people. Even with all the suspense, it is remarkable how often Hitchcock actually tells us what’s going to happen before it happens. For instance, at the opening of the film, Constance is dealing with a particularly troubled patient who is suffering from a severe guilt complex–and J.B., in the personage of Dr. Edwards, even meets with him. As we watch the patient’s condition accelerate in a downward spiral, Hitchcock is telegraphing what is happening to J.B. And of course, there is a darkly humorous irony in the patient with a severe guilt complex unknowingly consulting with an amnesiac with the same condition. Later in the film, when Constance and J.B. arrive at Dr. Brulov’s home, it is Dr. Brulov who tries to telegraph knowledge to Constance. He is obviously intelligent enough to see through their newlywed charade, and he says, “Women make the best psychoanalysts–until they fall in love. Then they make the best patients.” He’s telling her he knows what’s really going on. But by telegraphing some of the events of the story, Hitchcock is still not detracting from the suspense; rather he is adding tension by making the audience vastly uncertain of who knows what and how much.

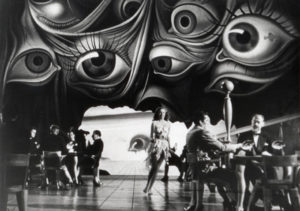

Surrealist imagery plays a huge role in Spellbound–appropriately enough, since both explore the inner workings of the human mind. Salvador Dali actually designed the set pieces for the dream sequences in the film. But it doesn’t stop there. There are several close-up shots of characters’ eyes; doors and mirrors and long corridors often appear both on screen and in dialogue, and an attempt to explain what is happening inside the minds of the characters. All of these visual themes appear in surrealist painting as well. For a film with a plot that centers on psychology and dream analysis, the surrealist tie-in is perfect–and another example of Hitchcock’s brilliance.

Now for a look at how Hitchcock uses Spellbound as a commentary on sexism. This commentary (we could even call it criticism) occurs on multiple levels and in multiple instances throughout the film–not to mention in the whole structure of the film, with the woman cast as the hero.

Almost the first thing we see in Spellbound is sexism in the workplace. All the other doctors whom Constance works with are men; she is the only woman, and she is also more intelligent and more promising, professionally speaking than all of them. Furthermore, her co-workers accuse her of being cold–an “ice queen”–because she is single and is not in love with any of them. And they obviously feel they have the right to make her personal life a source of open debate. Hitchcock is clearly throwing a negative light on the male doctors’ behavior, with Constance being the long-suffering professional woman trying to prove her worth in a man’s world.

The next instance where we see this commentary on sexism is in the way Constance is treated by men who are total strangers. When Constance goes in search of J.B., she sets up her own personal stakeout at his hotel. As she sits alone in the lobby, a man comes to sit beside her–and he’s so close he’s practically in her lap. He tries to engage her in conversation, but she is not interested in talking to him (after all, she doesn’t know him, and she has a lot on her mind). The rude stranger gets offended and accuses her of being snooty. While there is certainly plenty of humor and absurdity in the scene, Hitchcock is clearly commenting on the ridiculous way the stranger is behaving towards a woman he doesn’t know. What makes this scene so mind-blowing for me is that it is poignantly contemporary; just about every woman today has experienced this scenario, and Hitchcock was calling it out way back in 1945.

Hitchcock also demonstrates sexism in the way Constance is treated by men in authority. Constance is saved from the rude man by an ignorant one. The hotel detective accosts the boorish stranger and sends him away from Constance (though as soon as the detective steps away, the awful man snaps right back like a rubber band). The detective’s bravado overpowers his kindness, making his behavior toward Constance blatantly patronizing. Because the detective has saved her from the big bad wolf (rude stranger), he thinks he is a hero and she is helpless. He begins to ask Constance about herself and, obviously wanting to keep her motives as secret as possible, she lets him guess. He pegs her as a lost school teacher in search of her husband. Constance, as we know, is smart–and she leans into his ignorance and uses it to her advantage. She tells him he is right. He, in response, tells her that he’s “a bit of a psychologist”–having no idea that she has a doctoral degree on the subject, and that she is playing him for a fool. The detective later learns of his error, but Constance and J.B. are long gone.

Hitchcock also demonstrates sexism in the way Constance is treated by men in authority. Constance is saved from the rude man by an ignorant one. The hotel detective accosts the boorish stranger and sends him away from Constance (though as soon as the detective steps away, the awful man snaps right back like a rubber band). The detective’s bravado overpowers his kindness, making his behavior toward Constance blatantly patronizing. Because the detective has saved her from the big bad wolf (rude stranger), he thinks he is a hero and she is helpless. He begins to ask Constance about herself and, obviously wanting to keep her motives as secret as possible, she lets him guess. He pegs her as a lost school teacher in search of her husband. Constance, as we know, is smart–and she leans into his ignorance and uses it to her advantage. She tells him he is right. He, in response, tells her that he’s “a bit of a psychologist”–having no idea that she has a doctoral degree on the subject, and that she is playing him for a fool. The detective later learns of his error, but Constance and J.B. are long gone.

In addition to these specific instances, Hitchcock is flipping a major paradigm altogether. Hitchcock’s oeuvre contains no shortage of strong female characters–think Notorious or Rear Window–but they are usually leading ladies playing off of a leading man. In Spellbound, Ingrid Bergman is the HERO. Gregory Peck is the damsel in distress. Throughout the film, Constance is the strong one: she is the one figuring things out, and she is the one keeping them safe. Constance rescues J.B. from the authorities, the villain, and the prison of his own mind; she accomplishes this by being incredibly smart, extremely determined, and loving J.B. and believing in him and his innocence.

What is truly incredible about the way Hitchcock crafts the story of Spellbound and its characters is that Constance turns out to be exactly the type of hero that J.B. needs. We see this clearly when she is trying to convince Dr. Brulov to help her cure J.B. instead of calling the police. Through this conversation, we see that while Dr. Brulov certainly has the intelligence required to save J.B., he does not have the heart. Not that he is heartless–on the contrary, his main concern is Constance’s well-being and safety–but he views J.B. as a scientist views a subject. Constance, in contrast, considers him on a much more human level. She tells Dr. Brulov, “The mind isn’t everything. The heart can see deeper sometimes.” While Dr. Brulov’s comic anti-sentimentality is a refreshing break in the suspense of the film, it is not what is needed to rescue J.B. Constance’s love for him is one of the keys to saving him.

Not only was Constance the hero that J.B. needed, I think Hitchcock crafted the story in such a way that it needed a woman to be the hero. Furthermore, with all the commentary on sexism in this film, he clearly knew exactly what he was doing by reversing the roles–and I love and respect him and his work all the more. If you have never seen this movie, watch it. If you have seen this movie, watch it again. It will blow your mind.