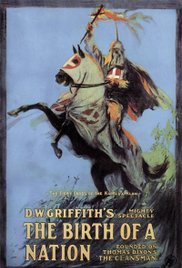

In 1915, director D.W. Griffith released The Birth of a Nation, the world’s first epic movie. It is a 3 hour and 10 minute film about the Civil War and the Reconstruction era from the perspective of the Confederacy, culminating in the formation of the Ku Klux Klan. Griffith was the son of a Confederate army colonel and was raised with the idea that the South had somehow been wronged during the events of the Civil War and the KKK were a brave group of vigilantes who sought justice for their wounded heritage. The film is certainly one of the most controversial movies ever released and resulted in riots, the murder of at least one young black man, and a resurgence of the KKK in Stone Mountain, Georgia. So does a film with such vile intentions have anything to say to us? Absolutely.

In 1915, director D.W. Griffith released The Birth of a Nation, the world’s first epic movie. It is a 3 hour and 10 minute film about the Civil War and the Reconstruction era from the perspective of the Confederacy, culminating in the formation of the Ku Klux Klan. Griffith was the son of a Confederate army colonel and was raised with the idea that the South had somehow been wronged during the events of the Civil War and the KKK were a brave group of vigilantes who sought justice for their wounded heritage. The film is certainly one of the most controversial movies ever released and resulted in riots, the murder of at least one young black man, and a resurgence of the KKK in Stone Mountain, Georgia. So does a film with such vile intentions have anything to say to us? Absolutely.

The Birth of a Nation is divided into two halves. The first half focuses on two families, the Stonemans from the North, and the Camerons from the south. They are friendly with each other and some of their offspring are romantically involved. Once the Civil War breaks out, the Stonemans and the Camerons are forced to meet on the battlefield. The first half of the movie is a down the middle Civil War story about how the war affects these two families and aside from some wacky politics (Griffith paints the South as victim to Abraham Lincoln’s big government agenda), it’s great. Griffith pioneered so many film making techniques that we take for granted in our modern day movie watching that when you realize this is the first time those ideas have been employed, it’s jaw-dropping. There is a battle sequence near the end of the first half wherein the North attacks Atlanta, Georgia and I would put it up against any modern day battle sequence. Aside from a few characters in black face that can be chalked up to an unfortunate side effect of the period in which it was made, and the aforementioned strange politics, the first half of the film doesn’t boast too much racist content. In fact, there is so little that I found myself uttering the famous last words of “Well this isn’t SO bad.” Little did I know what awaited me on the other side of intermission.

The second half sees Stoneman send his mixed-race right hand man, Silas Lynch, to the South to ensure that all is going well with the implementation of Reconstruction policies. After a rigged election wherein blacks are allowed multiple votes and whites are denied votes at all, South Carolina sees a mostly black state legislature with Lynch serving as lieutenant governor. Fed up with this “scourge,” the eldest son of the Cameron family concocts the idea that he should form a group of hooded vigilantes known as the Ku Klux Klan in order to scare the blacks out of South Carolina. Ultimately, of course, this idea works and the “triumphant” ending of the film sees black voters exiting their homes only to be greeted by lines of KKK members in the streets, intimidating them back into their homes. I wouldn’t have believed you if you told me this was an actual plot to a movie. I almost couldn’t believe it as the second half unfolded in front of me. The idea that people could sit in a movie theater and root for these characters oppressing their fellow man sickened me more than once during the film. But the final straw comes at the very end of the film when a title card reads:

The second half sees Stoneman send his mixed-race right hand man, Silas Lynch, to the South to ensure that all is going well with the implementation of Reconstruction policies. After a rigged election wherein blacks are allowed multiple votes and whites are denied votes at all, South Carolina sees a mostly black state legislature with Lynch serving as lieutenant governor. Fed up with this “scourge,” the eldest son of the Cameron family concocts the idea that he should form a group of hooded vigilantes known as the Ku Klux Klan in order to scare the blacks out of South Carolina. Ultimately, of course, this idea works and the “triumphant” ending of the film sees black voters exiting their homes only to be greeted by lines of KKK members in the streets, intimidating them back into their homes. I wouldn’t have believed you if you told me this was an actual plot to a movie. I almost couldn’t believe it as the second half unfolded in front of me. The idea that people could sit in a movie theater and root for these characters oppressing their fellow man sickened me more than once during the film. But the final straw comes at the very end of the film when a title card reads:

“Dare we dream of a golden day when the bestial War shall rule no more. But instead — the gentle Prince in the Hall of Brotherly Love in the City of Peace.”

We are then treated to a visual featuring War, the horseman of the apocalypse, attacking an unsuspecting group of white people, followed by an image of Jesus coming in to save these white people from the clutches of War. I have never been more relieved that a movie had come to a close in all my life. The thought of Griffith using something as liberating as the love of God to justify his racism is appalling enough, but to see it writ so clearly left me gobsmacked. But after a lot of thoughtful analysis, I came to this conclusion: most film buffs should see this movie.

It’s evil and disgusting and to see our faith twisted to justify such horrific behavior and should illicit a strong reaction out of everyone on the right side of this issue. But, on the other hand, The Birth of a Nation is exceedingly well made. The pacing is tight, the story structure is elegant, the way it chooses to reveal its story to the viewer is intelligent and allows you to watch the movie without holding your hand to explain what’s going on, etc. If I were a film professor, this movie would never leave my curriculum. The technical merits certainly do not outweigh the deplorable message of the film, and every opportunity must be taken to denounce this message, but they are what has kept it in the conversation for the last 101 years. Upon Griffith’s death, Charlie Chaplin said that Griffith was “the teacher of us all” and I am inclined to agree. His techniques have stood the test of time and he perfected them right out of the gate. The Birth of a Nation is an evil piece of racist propaganda that was used to an unfortunate end. It is a brilliant and compelling piece of art that young filmmakers should look to for ideas on how to craft a propulsive narrative and structure it in an intelligent way. Those two statements don’t discount each other, but they must be considered equally.

In November of 2015, one hundred years after the release of The Birth of a Nation, I had the opportunity to visit The Tennessee State Museum in Nashville. It’s a sprawling facility that covers the history of the state of Tennessee; beginning with its indigenous peoples and ending with the reconstruction era. They have sections of tree trunk you can still see artillery lodged in, gigantic, battle-worn confederate flags, canons, etc. But the piece that stuck with me the most was a plain pair of linen pants. They were white and unremarkable, but the placard below them read “pants belonging to an unknown slave.” Right above the pants hung a poster announcing a slave auction. I looked at my wife with tears in my eyes and choked out “those belonged to a slave.” While I was watching The Birth of a Nation, I kept flashing back to that pair of pants. I found myself thinking about the man who wore them and what life was like for him. Whether he was around to see emancipation, or if the abuses of slavery took his life early. When I think about the atrocities carried out in the name of God throughout history, I’m reminded of these verses from Galatians:

In November of 2015, one hundred years after the release of The Birth of a Nation, I had the opportunity to visit The Tennessee State Museum in Nashville. It’s a sprawling facility that covers the history of the state of Tennessee; beginning with its indigenous peoples and ending with the reconstruction era. They have sections of tree trunk you can still see artillery lodged in, gigantic, battle-worn confederate flags, canons, etc. But the piece that stuck with me the most was a plain pair of linen pants. They were white and unremarkable, but the placard below them read “pants belonging to an unknown slave.” Right above the pants hung a poster announcing a slave auction. I looked at my wife with tears in my eyes and choked out “those belonged to a slave.” While I was watching The Birth of a Nation, I kept flashing back to that pair of pants. I found myself thinking about the man who wore them and what life was like for him. Whether he was around to see emancipation, or if the abuses of slavery took his life early. When I think about the atrocities carried out in the name of God throughout history, I’m reminded of these verses from Galatians:

“For as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ. There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. And if you are Christ’s, then you are Abraham’s offspring, heirs according to the promise.” -Galatians 3:27-29

We serve a God who can erase the scars of those heinous acts and make the oppressed whole again. The history depicted in The Birth of a Nation is sad, but it is history. To deny it is to lie by omission, but to support it is to work in direct opposition of God. As followers of Christ, we should know our history in order that we do not allow the darkest parts of it to be repeated. That is why The Birth of a Nation will remain a vital piece of art that must be reckoned with.