What do you think of when you imagine vampires? Perhaps you think of Bela Lugosi in the classic 1931 Dracula. Or you might think of the recently passed Christopher Lee, star of 10 vampire movies with one of the more prominent modern vampire looks. Or perhaps you are influenced by more recent incarnations of the vampire mythos from TV shows like Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Angel, or True Blood. For the cereal enthusiast, your mind might go to Count Chocula. Personally, I’m a Boo-Berry fan.

What do you think of when you imagine vampires? Perhaps you think of Bela Lugosi in the classic 1931 Dracula. Or you might think of the recently passed Christopher Lee, star of 10 vampire movies with one of the more prominent modern vampire looks. Or perhaps you are influenced by more recent incarnations of the vampire mythos from TV shows like Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Angel, or True Blood. For the cereal enthusiast, your mind might go to Count Chocula. Personally, I’m a Boo-Berry fan.

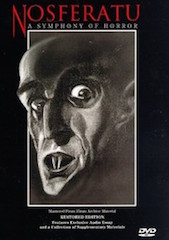

Breakfast choices aside, whatever first pops into your mind, the vampire mythos as it appears on-screen owes its origins and muse to F.W. Murnau’s 1922 silent film, Nosferatu, an unofficial but inspired adaptation of Bram Stoker’s 1897 Gothic novel, Dracula. It was the first time a full-length feature had been devoted to Stoker’s vision of the ancient supernatural monster. In fact, the story and inspired features of the film were so close to the author’s book that his estate sued, won, and ordered all copies of the movie destroyed. It was only through the zealous preservation of early fans of the film to keep prints from being destroyed and though it was stopped from premiering in Germany, it premiered seven years later in the US in 1929.

While the history of the movie can be just as interesting as the film itself, Murnau’s film is not a cult classic merely for its juicy, headline grabbing behind-the-scenes details, but for opening up the collective cinematic imagination to vampiric lore and all its narrative and thematic riches.

As the tale opens, we meet Hutter and his wife, Ellen; clear stand-ins for Stoker’s Jonathan and Mina Harker. Hutter is sent by his employer, the sinister-looking Knock, to visit a new client, Count Orlok (Max Schreck). When he arrives at his destination, he stops in an inn to find rest, only to find an agitated people that are only further agitated when Hutter names Count Orlok’s castle as his destination. The denizens of the small town won’t even see him past the bridge to the castle, and that is where Hutter’s trip goes from strange to sinister.

His previous night in the small inn, he had found a book warning him of Nosferatu, a creature from “the seed of Belial”, that lives in coffins filled with cursed dirt tinged with the Black Death. He laughs it off and sleeps soundly, only to be confronted with stranger and more terrifying things as he approaches the castle. The Count’s servant arrives in a horse-drawn carriage to shuttle Hutter to the castle and it whirls through the frame with a frightening, other-worldly speed that is a delightful camera special effect by Murnau. As the carriage is whisked along, Muranu employs a negative of the film to achieve a white tree effect that enhances the darkness and unease. One thing that becomes clear is that movie is about a slow build of horror and haunting atmosphere. It doesn’t boast all the manipulations and tricks modern horror has used to scare us, but frightens us with a more realistic, torturous creeping from the corners.

When we finally see the Count, he ascends out of the darkness of his cavernous castle to meet Hutter. After a tenuous dinner scene where Orlok terrifies Hutter pining about his “beautiful blood” and his wife’s “lovely neck”, Hutter is confronted by Orlok as Nosferatu. The iconic images of Nosferatu framed in the fireplace when Hutter looks out the door, and then the demonic vampire framed in the doorway, still bring an audible gasp from me. Unlike Lugosi or Lee’s Dracula, or most iterations of vampires since Lugosi’s portrayal of Count Dracula, Nosferatu is inhuman, grotesque, and almost animal. It’s a genuinely gripping moment from a film that can seem to drag for most modern viewers.

When we finally see the Count, he ascends out of the darkness of his cavernous castle to meet Hutter. After a tenuous dinner scene where Orlok terrifies Hutter pining about his “beautiful blood” and his wife’s “lovely neck”, Hutter is confronted by Orlok as Nosferatu. The iconic images of Nosferatu framed in the fireplace when Hutter looks out the door, and then the demonic vampire framed in the doorway, still bring an audible gasp from me. Unlike Lugosi or Lee’s Dracula, or most iterations of vampires since Lugosi’s portrayal of Count Dracula, Nosferatu is inhuman, grotesque, and almost animal. It’s a genuinely gripping moment from a film that can seem to drag for most modern viewers.

Hutter, when confronted by Orlok, is driven to madness and is only saved by a supernatural premonition his wife has of his impending doom. Somehow, never explained but surely some supernatural doing, Orlok’s hunger for blood focuses his aims on Hutter’s home city of Bremen. He leaves quite suddenly for Bremen and Hutter follows to try and return the way he came.

Orlok packs up his coffins, as any self-respecting vampire would do for a long journey, and attaches himself to a ship sailing for Bremen. On the ship, his presence spreads like the plague, the Black Death that is often referred to and the people’s explanation for Noferatu’s unexplained attacks. When the captain and first mate become suspicious of a mysterious presence aboard their vessel, the first mate goes down to the ship’s hold to root out the supposed intruder. In the film’s most iconic image, Orlok rises out of his coffin, mortis-like, with claws, ears, and fangs fully pointy, and he takes over the ship. In the 1920’s, this image would have genuinely scared audiences, but now, not so much. However, it is much more appropriate to recognize what that image meant in the past and also the beauty of Murnau’s imagery, use of shadow, and narrowing of the frame to heighten the drama of the image.

Another quick note on image. Murnau was influenced by German Expressionism, something we have discussed in previous Reviewing the Classics posts when discussing The Cabinet of Dr. Calgary and Metropolis. While those movies used painted and exaggerated backgrounds consistent with Expressionism, as did the other movies we have written about from the silent era, Murnau does not do this. He uses exquisitely captured landscapes and real buildings. His expert craft with photographing the mountains and Orlok’s castle, as well as the city buildings, add an element of realism while still being expressionist. It’s quite a fascinating difference that plays well with the story on screen.

Another quick note on image. Murnau was influenced by German Expressionism, something we have discussed in previous Reviewing the Classics posts when discussing The Cabinet of Dr. Calgary and Metropolis. While those movies used painted and exaggerated backgrounds consistent with Expressionism, as did the other movies we have written about from the silent era, Murnau does not do this. He uses exquisitely captured landscapes and real buildings. His expert craft with photographing the mountains and Orlok’s castle, as well as the city buildings, add an element of realism while still being expressionist. It’s quite a fascinating difference that plays well with the story on screen.

The final act of the movie focuses on Orlok’s inhabiting of the city of Bremen. The populace succumbs to a supernatural fear that grips them with Orlok’s presence, and combined with Orlok’s night prowlings, the city is overrun with death and a specter of dread. It is only when Ellen, Hutter’s wife, discovers the book Hutter had taken from the hotel, and reads that the only way to defeat the devilish Nosferatu is the sacrifice of an innocent maiden. Ellen becomes that sacrifice, by her own volition, and Orlok is famously vanquished not by a stake to the heart, as was common lore with vampires at the time, but by the rising sunlight. This would go on to establish an important new aspect of vampires; sunlight didn’t just make them weakened but would kill them.

But what greater narrative elements are at work? While the movie operates on a very simple plot structure with little deviation, the movie is still considered an early work of horror. The genre has almost universally been a vessel used as a stand-in for our collective fears. The movie references the black plague, something people of the movie’s time period would have feared. However, the beauty of horror, and of Nosferatu, is the darkness and dread being the fears of its audience. Whether it is the 1980’s and our culture feared AIDS, or today’s fear of climate change, or the fears of of the Cold War that led to aliens and space invader movies.

But what greater narrative elements are at work? While the movie operates on a very simple plot structure with little deviation, the movie is still considered an early work of horror. The genre has almost universally been a vessel used as a stand-in for our collective fears. The movie references the black plague, something people of the movie’s time period would have feared. However, the beauty of horror, and of Nosferatu, is the darkness and dread being the fears of its audience. Whether it is the 1980’s and our culture feared AIDS, or today’s fear of climate change, or the fears of of the Cold War that led to aliens and space invader movies.

Nosferatu understood the collective power of fear. The villagers, in need of a scapegoat and with nothing else to blame but rats and a mysterious plague, latch on to Knock, Hutter’s ugly and mad boss, as the culprit and “the vampire” and drive him out of the city. It’s as if the movie was well aware that our collective societal fears can drive us to find someone or something to blame it on and turn our wrath on those things, hoping to purge the fear from among us.

What the movie offers as a cure to our fears is not a collective wrath, which can be misguided or even downright false, but sacrifice. Ellen, in a selfless act, gives up love and life to ensure the survival of not only her husband but the entire surviving population of the city. Often, the greatest blow we can deal to evil and injustice is not to blood it with swift retribution, but to bleed in sacrifice and service for others. Nosferatu does not meditate long on this reality, but clearly wants us to know that fear and death are real, but hope and triumph over those things are just as real.