How does one go about remaking Dario Argento’s blood-splattered hallucination Suspiria? One doesn’t. Were one to try they would wreck upon the shoals of its bewildering non-plot and nightmarish visual logic. The most a writer or director can do is homage: pay respects to the tenor of the original and interrogate its morphology.

How does one go about remaking Dario Argento’s blood-splattered hallucination Suspiria? One doesn’t. Were one to try they would wreck upon the shoals of its bewildering non-plot and nightmarish visual logic. The most a writer or director can do is homage: pay respects to the tenor of the original and interrogate its morphology.

Luca Guadagnino’s Suspiria is a key which unlocks the repressed, subterranean substance of the 1977 original. Suspiria (2018) is an expansive midrash on the subtext of Suspiria (1977) which no one could have recognized was subtext until this reimagining had explored it. “Every writer creates his own precursors,” Jorge Luis Borges, author of fantastic fiction, once wrote; so here, the naming of this film does more to identify it as a successor to Suspiria 1977 than its themes, plot, or visual style. The names of its principal characters are the same, but Guadagnino commandeers these elements to effect a mirror of the original no one could have foreseen.

Borges’ use of the male pronoun, above, highlights how even he was beholden to the modes of production endemic to his time and place. These modes are partially challenged, partially upheld in Suspiria (2018). Women quantitatively dominate the scene, though its narrative world assumes the socio-political dominance of males. Those males present as blundering idiots for the most part—not that unlike the primary world we inhabit. What is accomplished in and by their rule seems to take effect through chance or by other forces at work within them.

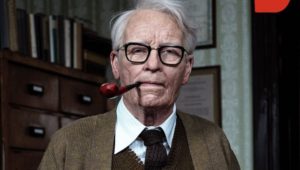

Even the best of them, elderly psychologist Josef Klemperer (Tilda Swinton), mostly represents a stultifying status quo. Klemperer’s patient, Patricia, comes to him with frightening revelations of witchcraft in their midst which he immediately categorizes as delusion. Klemperer exemplifies the emasculated inertia of patriarchy, distrustful of women’s experience, disbelieving in the extra-sensory, and is glacially slow to act. Klemperer is a Jewish survivor of the Holocaust who waited too long to aid his wife’s escape from the country. Burdened by guilt and heartbroken by her absence, he nevertheless fails to heed Patricia’s warnings until it’s too late.

Even the best of them, elderly psychologist Josef Klemperer (Tilda Swinton), mostly represents a stultifying status quo. Klemperer’s patient, Patricia, comes to him with frightening revelations of witchcraft in their midst which he immediately categorizes as delusion. Klemperer exemplifies the emasculated inertia of patriarchy, distrustful of women’s experience, disbelieving in the extra-sensory, and is glacially slow to act. Klemperer is a Jewish survivor of the Holocaust who waited too long to aid his wife’s escape from the country. Burdened by guilt and heartbroken by her absence, he nevertheless fails to heed Patricia’s warnings until it’s too late.

These points illustrate well how Guadagnino’s Suspiria is more a refraction than a remake. It takes up the starting threads of Argento’s story: American student Susie Bannion (Dakota Johnson) arrives at a prestigious German dance academy and discovers that it’s operated by a coven of witches. But from that premise an entirely different tapestry is woven, one that is soaked in just as much blood as the original, even if its gore isn’t distributed across its run time as uniformly. Guadagnino’s reimagining relies much more on dread and unease prior to its horrifically violent climax.

That climax is also the point at which the 2018 iteration reveals its vision as radically different from Argento’s, in that Guadagnino actually has one: an examination of heritage and the burden of historical existence. Argento, as is usual, doesn’t bother to thematically tie his plot’s threads together as his principal interest is a conceit to loosely organize a string of murders. The significance of any Argento film only ever arises from the symbolic content that is always already inscribed within the imagery he gathers together and sets in sequence in his films. As a director he is a pair of eyes, largely uninterested in the mechanics of character or plot. He is a weaver of nightmares, not a prophet.

Guadagnino’s iteration relocates the dance academy to West Berlin, situating it directly in front of the Wall. It’s set in the same period as the original— Autumn 1977— but the real, historical state of emergency gripping West Germany plays a pivotal role in the film’s ethos. A divided country at war with itself over its heritage forms the macrocosmic backdrop to the struggle for power and identity playing itself out at the academy. According to philosopher and critic Philipe Lacoue-Labarthe, the Holocaust is the revelation of modernity and of western civilization, the revelation which “opens up, or closes, a quite other history than the one we have known up until now.”[1] We Moderns tend to prize and praise knowledge, but knowledge can be a curse just as much as a blessing. What are we to do with the truth of history when we learn it? Will we follow the course that is already in motion? Or will we open ourselves up to death by resisting it?

Guadagnino’s iteration relocates the dance academy to West Berlin, situating it directly in front of the Wall. It’s set in the same period as the original— Autumn 1977— but the real, historical state of emergency gripping West Germany plays a pivotal role in the film’s ethos. A divided country at war with itself over its heritage forms the macrocosmic backdrop to the struggle for power and identity playing itself out at the academy. According to philosopher and critic Philipe Lacoue-Labarthe, the Holocaust is the revelation of modernity and of western civilization, the revelation which “opens up, or closes, a quite other history than the one we have known up until now.”[1] We Moderns tend to prize and praise knowledge, but knowledge can be a curse just as much as a blessing. What are we to do with the truth of history when we learn it? Will we follow the course that is already in motion? Or will we open ourselves up to death by resisting it?

World-renowned dance instructor Madame Blanc (also Tilda Swinton) has played her part in the coven and has groomed Susie for becoming a vessel for Madame Markos (Tilda Swinton, a third time!), the head of the coven who claims to be the ancient witch-goddess Mater Suspiriorum. But something has changed. Blanc now identifies with Susie—a latent maternal instinct blooming as a result of their intense pedagogical relationship. There is nothing sentimental to it: Blanc is as hard as nails with her pupil. But the mother-daughter dynamic that develops between them subverts her priorities. She finds herself unable to carry out the coven’s plan to present Susie to Markos, for she has moved from identification with and furtherance of the coven’s goals to empathy for Susie.

But that shift is interpreted by Markos as weakness and insubordination. Blanc had, after all, opposed Markos’ election to leadership of the coven and had sought it for herself. She was promised there would be no bad blood between them due to that opposition, but when the moment comes and she tries to persuade Susie not to give herself to the ritual, the insecure fear that characterizes stratified hierarchy kicks in. In a fit of rage, Markos nearly decapitates Blanc before Susie’s eyes.

But that shift is interpreted by Markos as weakness and insubordination. Blanc had, after all, opposed Markos’ election to leadership of the coven and had sought it for herself. She was promised there would be no bad blood between them due to that opposition, but when the moment comes and she tries to persuade Susie not to give herself to the ritual, the insecure fear that characterizes stratified hierarchy kicks in. In a fit of rage, Markos nearly decapitates Blanc before Susie’s eyes.

“If you accept me, you must put down the woman who bore you. Think of that false mother now,” Markos tells Susie. “Expel her. You have the only mother you need here. Death to any other mother!” But this hypocritical imperative leads to her undoing. For she is an impostor. Her claim to be Mater Suspiriorum is unmasked as false when the true Mater Suspiriorum reveals herself— Susie. She has come to set the coven in order and punish those who have perpetrated evil in her name.

This becomes the focus of the film’s climax. Who are the legitimate inheritors of tradition? And where is genuine authority to be found? Suspiria (2018) centers itself around these questions, albeit in a slightly ironic key. For given its grand departures from the Argento original, we are effectively given a belated text and told to assign it greater interpretative weight than the original. Is this a creative misreading, as literary critic Harold Bloom would claim? Constructive “misreading”, in his poetics, allows the belated artist to “clear imaginative space for themselves.” Suspiria (2018), on this view, would employ the revisionary ratio tessera, wherein the successor artist negatively builds from her influence “by so reading the parent-poem as to retain its terms but to mean them in another sense, as though the precursor had failed to go far enough.” [2]

In its elaboration on the socio-political milieu which the Argento original completely neglected, Guadagnino’s Suspiria calls that silence to account. It failed to go far enough. What was Argento’s story protecting itself from in detangling itself so completely from its own contemporary context? In taking up the foment and the terror of the German Autumn, Suspiria (2018) recasts Argento’s macabre fairy tale as a question: What will we do with our knowledge? The German Autumn drew its energies from the post-war generation’s recognition that their parents were complicit in the Nazi atrocities the nation wanted to distance itself from. That the insurgents, in their rejection of that national past, unleashed a wave of terror of their own should come as no surprise given the sins of their forebears.

In its elaboration on the socio-political milieu which the Argento original completely neglected, Guadagnino’s Suspiria calls that silence to account. It failed to go far enough. What was Argento’s story protecting itself from in detangling itself so completely from its own contemporary context? In taking up the foment and the terror of the German Autumn, Suspiria (2018) recasts Argento’s macabre fairy tale as a question: What will we do with our knowledge? The German Autumn drew its energies from the post-war generation’s recognition that their parents were complicit in the Nazi atrocities the nation wanted to distance itself from. That the insurgents, in their rejection of that national past, unleashed a wave of terror of their own should come as no surprise given the sins of their forebears.

“Who will narrate the identity of Germany?” was the question animating the activists and terrorists of the German Autumn. And in Guadagnino’s Suspiria the question that sets the film in motion is, “Who will speak for Mater Suspiriorum?” Many will exploit her name to do as they please with impunity, and one will even speak as her to enact her own agenda. Wrenching control of the narrative becomes the film’s chief burden.

And this is where its biggest departure from the original becomes so pivotal. The 2018 film’s re-characterization of Susie problematizes the nature of witchcraft and evil in this mythos. In the Argento original, witches are unambiguously evil. But in recasting Susie— no longer the heroine who succeeds in toppling the coven, as in Argento’s version— as the reincarnation of Mater Suspiriorum, the film renders a different judgment. Susie is depicted as one who, in severing Markos’ diseased head from leadership, rights a grievous wrong and restores an ideal. The film implicitly suggests the coven’s powers and practices are at least neutral, or possibly even good, though susceptible to corruption. Susie is portrayed as vivacious and compassionate in contrast to the undead, disgusting Markos. But more than that, she is an avenger for all the women who have been crushed by the coven’s bids for power.

And this is where its biggest departure from the original becomes so pivotal. The 2018 film’s re-characterization of Susie problematizes the nature of witchcraft and evil in this mythos. In the Argento original, witches are unambiguously evil. But in recasting Susie— no longer the heroine who succeeds in toppling the coven, as in Argento’s version— as the reincarnation of Mater Suspiriorum, the film renders a different judgment. Susie is depicted as one who, in severing Markos’ diseased head from leadership, rights a grievous wrong and restores an ideal. The film implicitly suggests the coven’s powers and practices are at least neutral, or possibly even good, though susceptible to corruption. Susie is portrayed as vivacious and compassionate in contrast to the undead, disgusting Markos. But more than that, she is an avenger for all the women who have been crushed by the coven’s bids for power.

But the problem is this: the cult draws its energies from the same destructive powers the Nazis unleashed only a generation prior to Suspiria (1977). This power presents itself as enlightened, erotic, and liberative, but that which it is tapped into is the same: Death. Patriarchy and matriarchy alike are united under its dominion; both unleash it upon the world. Susie summons Death to liquidate those members of the coven who elected Madame Markos to leadership. While this is suggestive of retributive justice arcing around to deliver its recompense, the fact remains that the ritual dance (the “Volk”) which empowers Markos was created in 1944 while the Final Solution was being enacted.

Perhaps the dance had no direct connection to Germany’s possession by evil powers, but it’s a live question. The dance’s name, “Volk,” is German for “people,” a crucial component of the Nazis’ blood and soil ideology. We also learn from the coven’s originally intended victim, Patricia, that the coven has been underground since the war. Whether this was because the collapse of the Third Reich left them vulnerable without sympathetic structures of power to back them or because the drab, lifeless conformity of Soviet occupation drove them into hiding is left unexplained. Perhaps the most important connection that is made between the coven and the Reich is made by Klemperer, who says that the religious delusions of the coven at the academy and of the Reich are the same.

Perhaps the dance had no direct connection to Germany’s possession by evil powers, but it’s a live question. The dance’s name, “Volk,” is German for “people,” a crucial component of the Nazis’ blood and soil ideology. We also learn from the coven’s originally intended victim, Patricia, that the coven has been underground since the war. Whether this was because the collapse of the Third Reich left them vulnerable without sympathetic structures of power to back them or because the drab, lifeless conformity of Soviet occupation drove them into hiding is left unexplained. Perhaps the most important connection that is made between the coven and the Reich is made by Klemperer, who says that the religious delusions of the coven at the academy and of the Reich are the same.

This newest rendition of Suspiria doesn’t entirely succeed in all of its ambitions. Its conceptualities awaken the imagination but their execution is uneven. But the exact same must be said of the original. The phantasmagoric fever dream of the original is less coherent—now there is an understatement—than Guadagnino’s version, but 2018 Suspiria’s attempts at gravity by association/historical echo, while often intriguing, dissipates into moral incoherence. Much is insinuated, but the threads aren’t drawn together into a unity. Why, for instance, do the witches castigate Klemperer for not believing Patricia’s testimony when they are the ones who abducted her and left her to rot within the bowels of the school? Why, after demonstrating the uselessness of men, does the coven need a male witness for its succession of leadership? These aren’t mysteries— they’re irritating inconsistencies, and there is a vital difference between the two.

If we are going to tell the truth about our precursors, about the cloth from which we have been cut, then we must interrogate the ideals that have been passed on to us and call into question the mirrors we presume reflect reality. Might they conceal an entrance to a room we would prefer to pretend doesn’t exist? “Look closer,” is the plea Dr. Klemperer gives the doomed Sara. We all must look closer though we are afraid of what we will find behind and underneath the surfaces of the familiar. Hell is behind the door (as Helena Markos growls to Susie in the original), and Death lurks within that mirror. But the only legitimate hope we can have of escaping the gravitational pull of our historical location, of the zeitgeist which commandeers our intentions for its own purposes, is to name the wrongs that have been perpetrated by our tribe and renounce them. We must look beyond the mirror and heed the testimony of those who do not hold power to arrive at reality. It will cut against the narratives of the powerful and fall short of our own ideals. And in the same way, perhaps it’s the differential between these two films which is the ideal Suspiria.

If we are going to tell the truth about our precursors, about the cloth from which we have been cut, then we must interrogate the ideals that have been passed on to us and call into question the mirrors we presume reflect reality. Might they conceal an entrance to a room we would prefer to pretend doesn’t exist? “Look closer,” is the plea Dr. Klemperer gives the doomed Sara. We all must look closer though we are afraid of what we will find behind and underneath the surfaces of the familiar. Hell is behind the door (as Helena Markos growls to Susie in the original), and Death lurks within that mirror. But the only legitimate hope we can have of escaping the gravitational pull of our historical location, of the zeitgeist which commandeers our intentions for its own purposes, is to name the wrongs that have been perpetrated by our tribe and renounce them. We must look beyond the mirror and heed the testimony of those who do not hold power to arrive at reality. It will cut against the narratives of the powerful and fall short of our own ideals. And in the same way, perhaps it’s the differential between these two films which is the ideal Suspiria.

[1] (Heidegger, Art and Politics, trans. Chris Turner [Oxford: Blackwell, 1990], 45).

[2] (The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973], 14).

Ian Olson is another post-Barthian Thomist Midwesterner growing weary of irony and exhausted by scrupulosity. Paradoxically, though, that’s only fueled my passion to advertise and commend every fantasticity strewn throughout the cosmos by the One who does all things well. I’d rather talk up a gracious God than chalk it up to my ability. Can you dig it?

You can find his other work at Mockingbird and Grindhouse Theology.