Star Trek: The Next Generation is thirty years old this month! To celebrate, Redeeming Culture is assembling the finest crew of culture redeemers from all over the internet to investigate the spiritual harmonies in this cornerstone of science fiction.

For more about Trektember, read our preview post. Please note that there are minor plot spoilers for this episode below.

Kevin C. Neece hasn’t been relieved of duty yet; he’s back to talk about Season 6’s classic 2-parter: episodes 10 and 11, Chain of Command I and II.

• •

Recap

A huge shakeup occurs on the Enterprise when Captain Picard is relieved of command by Captain Edward Jellico, who assumes the center seat in his place; and Dr. Crusher and Lt. Worf are reassigned. Tensions immediately rise after the abrupt and unexplained change, especially in response to Jellico’s brusque, demanding leadership style. But behind the scenes, Picard, Crusher, and Worf are on a top secret mission to stop the Cardassians from developing and using a devastating biological weapon. During the operation, however, Picard is captured by the Cardassians and tortured extensively, leaving Jellico forced to abandon him rather than risk all-out war with Cardassia.

A huge shakeup occurs on the Enterprise when Captain Picard is relieved of command by Captain Edward Jellico, who assumes the center seat in his place; and Dr. Crusher and Lt. Worf are reassigned. Tensions immediately rise after the abrupt and unexplained change, especially in response to Jellico’s brusque, demanding leadership style. But behind the scenes, Picard, Crusher, and Worf are on a top secret mission to stop the Cardassians from developing and using a devastating biological weapon. During the operation, however, Picard is captured by the Cardassians and tortured extensively, leaving Jellico forced to abandon him rather than risk all-out war with Cardassia.

Review

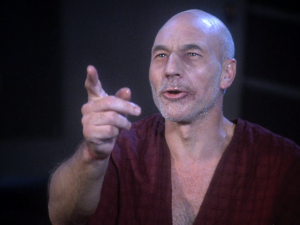

One of the top-tier moments in The Next Generation, “Chain of Command” is of course most famous for the extensive interplay between Patrick Stewart and David Warner (as Picard and Gul Madred, respectively) during Picard’s captivity in the second episode of the two-part story. The two former Royal Shakespeare Theatre colleagues give multi-layered and absorbing performances of a screenplay written to highlight the brutality and cruelty of torture.

One of the top-tier moments in The Next Generation, “Chain of Command” is of course most famous for the extensive interplay between Patrick Stewart and David Warner (as Picard and Gul Madred, respectively) during Picard’s captivity in the second episode of the two-part story. The two former Royal Shakespeare Theatre colleagues give multi-layered and absorbing performances of a screenplay written to highlight the brutality and cruelty of torture.

The episodes have the distinction, however, of also providing one of the most compelling framing stories of the series. While everything that happens on the Enterprise is essentially setup for the interrogation scenes, the story shows the crew adapting to very difficult circumstances, with varying degrees of success. It also gives us, in Jellico, a difficult character to like—who actually turns out to have done the right thing all along. The episode’s ability to humanize characters on every side of its narrative (even Gul Madred) strengthens the drama and reinforces its philosophical grounding.

The episodes have the distinction, however, of also providing one of the most compelling framing stories of the series. While everything that happens on the Enterprise is essentially setup for the interrogation scenes, the story shows the crew adapting to very difficult circumstances, with varying degrees of success. It also gives us, in Jellico, a difficult character to like—who actually turns out to have done the right thing all along. The episode’s ability to humanize characters on every side of its narrative (even Gul Madred) strengthens the drama and reinforces its philosophical grounding.

Reflection

No Name But Human

Speaking of that philosophical grounding, the essential story here both is and isn’t about torture. Certainly, the episode exists to communicate the message that torture is both inhumane and ineffective—or rather, that it is effective at doing nothing but breaking and manipulating the human psyche. It was even made in cooperation with Amnesty International, who consulted on the episode for that very purpose.

Speaking of that philosophical grounding, the essential story here both is and isn’t about torture. Certainly, the episode exists to communicate the message that torture is both inhumane and ineffective—or rather, that it is effective at doing nothing but breaking and manipulating the human psyche. It was even made in cooperation with Amnesty International, who consulted on the episode for that very purpose.

But the core of the story comes in a small scene that is often forgotten. It opens in the room where Madred is torturing Picard as Madred is instructing his daughter in the care of her pet. Referring to Picard, who is behind them, slumped on the chair in exhaustion, she asks, “Do humans have mothers and fathers?”

“Yes,” the Gul replies, with all gentleness and care, “but human mothers and fathers don’t love their children as we do. They’re not the same as we are.” The little girl then asks, “Will you read to me later?” Madred promises he will, and she exits. Here, we see that even this harsh, seemingly unfeeling Cardassian cares deeply for his daughter. And, like all parents who care for their children, he wants to provide a good life for her and pass on his most deeply held beliefs.

“Yes,” the Gul replies, with all gentleness and care, “but human mothers and fathers don’t love their children as we do. They’re not the same as we are.” The little girl then asks, “Will you read to me later?” Madred promises he will, and she exits. Here, we see that even this harsh, seemingly unfeeling Cardassian cares deeply for his daughter. And, like all parents who care for their children, he wants to provide a good life for her and pass on his most deeply held beliefs.

One of those beliefs, unfortunately, is an idea far too often passed down from generation to generation, very often by otherwise kind and loving parents: “They’re not the same as we are.”

Madred’s torture of Picard is not about information. It’s about power. And it is rooted in de-personalization. He strips Picard of his clothes and vows to no longer call him by name, but only to refer to him as “human.” It is his way of separating himself from Picard and allowing him to think of the captain as lesser, as other.

As seen in the horrific caricatures of Japanese and German soldiers as monsters and fiends during World War II, dehumanization is an important step toward harming and killing another person. It is so common that we often don’t even realize we do it. We make another less than us through a label, a marginalization, a categorization, and we perpetuate the lie that “They’re not the same as we are.”

As seen in the horrific caricatures of Japanese and German soldiers as monsters and fiends during World War II, dehumanization is an important step toward harming and killing another person. It is so common that we often don’t even realize we do it. We make another less than us through a label, a marginalization, a categorization, and we perpetuate the lie that “They’re not the same as we are.”

In light of this episode’s example, we might ask ourselves what are the labels we use, the words we spout, to help us view someone else as “other,” so that we may quietly consider ourselves superior to them, even in some small way?

[pullquote]What would happen if we took a cue from Picard’s torturer?[/pullquote]I wonder what would happen if we, strangely, took a cue from Gul Madred and ignored all those other names – “illegal,” “nonbeliever,” “sinner,” “criminal” – and replaced them with the one that really matters: “Human.” For, as Madred seeks to use that word to demean Picard, we know that human beings are created in the image of God and that we are called to love one another.

The name “Human” may have seemed shameful and degrading to Madred, but in truth, it is dignifying and uniting. Perhaps if we can see the horrors of torture and murder and war as outgrowths of the sin of dehumanization and fear of the other, we can begin to cut off the evil at its source, when we start to love one another by regarding one another as not at all that much different from ourselves.

• • •

Thanks for reading Trektember on Redeeming Culture. Tomorrow, Mark Wingerter looks back over his life and wonders how it would all have been different with his take on Tapestry.

• • •

Kevin C. Neece is the author of The Gospel According to Star Trek series and a speaker on media, the arts, and pop culture from a Christian worldview perspective.

Thank you for cutting to the very core of the issue. This was a weirdly timely piece for me to read today.

I’m very glad to hear that, David. It was then, if nothing else, written for you. 🙂