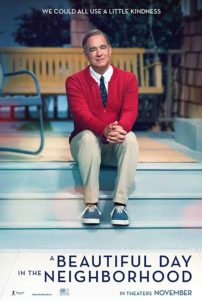

I usually wear a smartwatch; a round Android smartwatch which, while I like it, isn’t very good: in recent months, it’s taken to buzzing loudly for no particular reason a couple of times a day. I wish I could figure out why. So when I sat down in the theater to watch A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, I dutifully turned off the screen and silenced the watch as always, and allowed myself to be pulled back in time twenty-one years into a special new episode of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood made for grown-ups. Hosted by the beloved Tom Hanks as the legendary Fred Rogers, the episode—er, film—is touching and sweet and calming in all the ways you would expect it to be; at one point, in an intimate recreation of Rogers’ 1997 Lifetime Achievement Emmy acceptance speech, he asks his lunch companion to be quiet for one minute and think about “all the people who loved you into being.”

I usually wear a smartwatch; a round Android smartwatch which, while I like it, isn’t very good: in recent months, it’s taken to buzzing loudly for no particular reason a couple of times a day. I wish I could figure out why. So when I sat down in the theater to watch A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, I dutifully turned off the screen and silenced the watch as always, and allowed myself to be pulled back in time twenty-one years into a special new episode of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood made for grown-ups. Hosted by the beloved Tom Hanks as the legendary Fred Rogers, the episode—er, film—is touching and sweet and calming in all the ways you would expect it to be; at one point, in an intimate recreation of Rogers’ 1997 Lifetime Achievement Emmy acceptance speech, he asks his lunch companion to be quiet for one minute and think about “all the people who loved you into being.”

Slowly you realize that the rest of the diners in the restaurant have also gone quiet. And then the wait staff as well. The world stands still. The soundtrack is gone. The noises of the world outside fade away. Even the camera becomes slower, more deliberate, more flowing; it feels almost liturgical. There are several points in the film where reality seems to disconnect, and this is one of them, directed toward our side of the screen. The message is clear: yes, audience, you too; consider those people.

Remarkably, the silence does indeed last a full minute. Well, I assume it does; it felt like a minute, or even longer, and it’s not like Rogers (or Hanks) to lie. Still, I don’t know for sure, my watch was off.

Or I thought it was. A few moments into the silence, enforced by Rogers’ warm but insistent face, my watch decided to make its characteristic loud, unprompted buzz.

And then Mr. Rogers looked at me.

I gasped. The film’s previous fourth-wall breaks had been diegetic; Hanks as Rogers looks into the camera of his television show, of course, talking to the children of the world within the narrative, just like he did in our real world for thirty-one seasons. But this time, Rogers was breaking the actual fourth wall; looking at us in the theater, looking at me, at David. It was effective as so few such violations of this performance convention can be. I wasn’t just watching the film. Mr. Rogers wanted me to be in the film. He wanted me to be a part of it. He wanted me to grow through it. My watch made a noise, and he noticed. I became five years old again, and once again Mr. Rogers was talking to me directly.

From that minute on, the theater was quieter. It was clear that he had won us all over. We were bought in, and it no longer mattered that Tom Hanks doesn’t really look like Fred Rogers; when he announced the end of the minute, it was Mr. Rogers on the screen looking down upon, as journalist Tom Junod described them, “all his vanquished children.”

An Unashamed Insistence on Intimacy

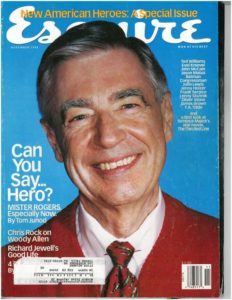

Junod, upon whom the character of Lloyd Vogel was based, really did write an article called “Can You Say…Hero?” in which he describes Rogers’ resistance to being interviewed and even insistence on interviewing his interviewer: “there was an energy to him,” Junod recalls; “a fearlessness, an unashamed insistence on intimacy.”

Junod, upon whom the character of Lloyd Vogel was based, really did write an article called “Can You Say…Hero?” in which he describes Rogers’ resistance to being interviewed and even insistence on interviewing his interviewer: “there was an energy to him,” Junod recalls; “a fearlessness, an unashamed insistence on intimacy.”

And so Rogers’ look directly at me in the theater is very much in character for the man. It didn’t feel creepy; it felt important, it felt weighty. Much of it was, of course, the meaning that I brought to it as a fan of Rogers for the past thirty-four years; of course, Hanks wasn’t looking “at me.” He was looking at the entire audience; at millions of people in theaters across the United States during that weekend. Nothing mystical or supernatural was happening.

Or was it?

Fred Rogers, an ordained Presbyterian minister, would’ve known the story of the prophet Jeremiah. The target of a conspiracy against him because of his prophecies, Jeremiah lamented his state; but, in chapter 12, speaks of his comfort despite his predicament:

But you, O Lord, know me;

you see me, and test my heart toward you.—Jeremiah 12:3a, ESV

What comforts us, what gives us hope when we’re hurting? Not vague platitudes, or even contextless scripture. Jeremiah isn’t comforted by the fact that God is strong, or that God is the Creator, or that He is the protector, or the Way, the Truth, or the Life. He is comforted that God knows him. We’re comforted by being known. That’s why the fourth-wall break in Neighborhood is so poignant.

“Such bravery!” Rogers says in the film, about people who opened up to him. Lloyd fights tooth and nail against being known – by his dad, by his wife, by Fred Rogers. In the end it is his salvation, but it’s no surprise that there’s fear in the knowing.

A powerful thing happens when we’re known; we’re stripped bare of everything we could hide behind, all our foibles and flaws and failures are made clear. And as much as Mr. Rogers insisted on intimacy with those around him, he never used it to harm or embarrass those who opened up to him; on the contrary, stories abound around the internet of Rogers sitting with complete strangers and talking for as long as they needed, or calling a person he had met only in passing to ask how they were and tell them that he was praying for them. Because he took the time to know them, Mr. Rogers was able to help them with what they needed. It has a powerful effect that goes beyond the human capacity for talk therapy or mere self-help; something in our hearts feels a transcendent change. That power is within all of us, but it feels mystical and supernatural when someone knows us because the power comes from God.

How much greater, then, is being known perfectly by God Himself?

Mr. Rogers was finite. He wasn’t perfect. He failed. And, sadly, he’s no longer alive. But God knows us; and did before we were even born (Jeremiah 1:5). He uses that knowledge to comfort, to love, and to pursue.

And oh, does He pursue.

He Looks, and then He Finds

Getting a good Hollywood script out of Mr. Rogers’ life is tough. He’s such an even-keeled, internally-motivated, consistent person that placing him as the protagonist is unfulfilling; we never see him grow or change, and we want that out of our protagonists because we want that out of ourselves.

Getting a good Hollywood script out of Mr. Rogers’ life is tough. He’s such an even-keeled, internally-motivated, consistent person that placing him as the protagonist is unfulfilling; we never see him grow or change, and we want that out of our protagonists because we want that out of ourselves.

Last year’s breathtaking documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor gets around this problem by focusing largely on the people Rogers affected; in essence, the world itself is—we are—the documentary’s protagonist. A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood takes a similar tactic, focusing on Lloyd Vogel’s life and problems. In each case, Rogers sees the problem, and like a wizard in a high fantasy story, swoops in with a power the protagonist doesn’t understand.

Neighborhood’s Joanne Rogers (the real version of whom appears in the aforementioned restaurant scene) chafes at the idea that “Rog” was a wizard or a saint. “If you think of him as a saint, then his way of living is unattainable.” Remembering him as perfect or deific is wrong and does him a disservice. But it’s undeniable that he had a special facility for seeking out those who needed help; using that God-given power to know others.

“He finds me,” Tom Junod says, “because that’s what Mister Rogers does—he looks, and then he finds.”

Pursuing “broken people” is something that our God has a particular penchant for. He pursued a rebellious nation of Israel; He pursued a defiant Jonah; He pursued an unbelieving Paul; he pursued every single Christian who ever professed faith in God, seeking to know them deeply and show His love. He finds us where we are.

But to pursue people faithfully, you have to be very steady; God knows this, which is why He is unchanging throughout time. Mr. Rogers’ calm, faithful pursuit of those in need echoes (and is empowered by) this Godly steadfastness.

And in that calm, faithful pursuit, God knows us.

But He won’t leave us where He finds us. He doesn’t change, but like a great Hollywood script, He’s written some dramatic growth into our futures.

A Voice of Authority

Mr. Rogers’ plain-spokenness and soft, friendly demeanor might lead you to believe that he’s a pushover. Here is where, I think, Tom Hanks’ portrayal of the man weakens the film a bit. Hanks doesn’t look much like Rogers, sure; but more than that, his voice is just too agreeable. The real Mr. Rogers had power in his voice; authority that demanded to be obeyed. “Mister Rogers was not some convenient eunuch but rather a man, an authority figure who actually expected [people] to do what he asked,” Tom Junod remembered. Even the powerful, the celebrated, the aloof found his voice arresting. And he deployed that authority in hopes of making people better: learn better, express their feelings better, feel their feelings better. He used the pursuit of people, the knowing of people, to create for them a safe place in which to grow, but he expected them to grow beyond what they were and become something better.

Mr. Rogers’ plain-spokenness and soft, friendly demeanor might lead you to believe that he’s a pushover. Here is where, I think, Tom Hanks’ portrayal of the man weakens the film a bit. Hanks doesn’t look much like Rogers, sure; but more than that, his voice is just too agreeable. The real Mr. Rogers had power in his voice; authority that demanded to be obeyed. “Mister Rogers was not some convenient eunuch but rather a man, an authority figure who actually expected [people] to do what he asked,” Tom Junod remembered. Even the powerful, the celebrated, the aloof found his voice arresting. And he deployed that authority in hopes of making people better: learn better, express their feelings better, feel their feelings better. He used the pursuit of people, the knowing of people, to create for them a safe place in which to grow, but he expected them to grow beyond what they were and become something better.

God does the same for us to an even greater degree: when He saves us, we are free to grow in Him without ever having to worry about falling out of His favor. We are free to pursue Him as He has pursued us. “You can be better,” God says. “I sent my Son to die so that you can be free of sin’s power. I sent my Holy Spirit to fill you so that you can be free of sin’s temptation. And I am here to know you perfectly so that you will seek me.”

A few years ago, the phrase “you aren’t being the person Mr. Rogers knew you could be” began going around the internet. At once soft and withering, light and damning, the phrase is a reminder that the power behind Mr. Rogers’ intimacy and pursuit of people in need was a certainty that people could be better. These ways of growing others are echoes of how God grew Mr. Rogers into…well, Mr. Rogers. He was who he was because Jesus made him that way; and he did what he did because Jesus gave him a heart for children. God doesn’t just allow us to grow, or give us the strength to grow, He expects us to grow (Revelation 3:16).

And because He knows us and intimately pursues us, we will. It’s not a threat, or a warning; it’s an expression of fact. His warmth and knowledge of us makes us sure; we will grow and become the people He wants us to become.

The real power of A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood is in the fact that it embodies Mr. Rogers in a unique way; more than just telling his story, it does his work. It insists on intimacy. It pursues and finds. It expects us to grow. This film isn’t about Mr. Rogers.

It is Mr. Rogers.

1 comment