John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), is both a great Western and a surprisingly rich political film. Liberty Valance has an interesting, complex story, but behind it is an examination of Justice and how it applies to American culture in particular. For years, scholars have argued that the film presents ideas from Plato, Aristotle, Locke and Hobbes. Though there is little agreement about what Ford is trying to say, there is near universal agreement that Ford is wrestling with fundamental questions about the kind of society we should be. I’ll briefly overview the plot and point out some of the ways Ford uses the Western to get viewers to wrestle with Justice in modern society. Because Justice and the lack of it is a perennial problem, Ford’s film is just as important today as it was a half a century ago.

John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), is both a great Western and a surprisingly rich political film. Liberty Valance has an interesting, complex story, but behind it is an examination of Justice and how it applies to American culture in particular. For years, scholars have argued that the film presents ideas from Plato, Aristotle, Locke and Hobbes. Though there is little agreement about what Ford is trying to say, there is near universal agreement that Ford is wrestling with fundamental questions about the kind of society we should be. I’ll briefly overview the plot and point out some of the ways Ford uses the Western to get viewers to wrestle with Justice in modern society. Because Justice and the lack of it is a perennial problem, Ford’s film is just as important today as it was a half a century ago.

The majority of the film takes place in an extended flashback sequence. Senator Rance Stoddard (Jimmy Stewart) and his wife (Vera Miles) have arrived in the city of Shinbone for a friend’s funeral. When the reporters find out about the senator’s arrival, they demand to know who this friend is that could bring one of the most politically powerful men to town. While his wife Hallie tours the town, Stoddard tells the reporters about Tom Doniphon, Liberty Valance, and the real history of Shinbone.

The film flashes back to Stoddard traveling West to set up his legal practice when his stagecoach is robbed by Liberty Valance.. Valance (Lee Marvin) and his gang hold up Stoddard’s stagecoach. As they rob the passengers, they try to take a pin from a widow that her late husband bought her, and when Stoddard tries to intervene, Valance beats him. As Valance riffles through the passengers’ belongings, he finds Stoddard’s law books. Valance tears apart his law books, demands to know what kind of man Stoddard is coming to the West armed with nothing but law books, and literally horsewhips him.

Stoddard is rescued when local rancher Tom Doniphon (John Wayne) brings him to the family that runs the local restaurant for care. Stoddard demands to make his own way and covers his debt to the family by washing their dishes. This film does have the stereotypical man in white as the hero; instead of the white hat, Stoddard dons the white apron. In a scene that shows the optimism or naiveté of Stoddard, as he washes and looks through his law books, he finds a statute he believes will be useful in brining Valance to justice and says that he’s finally got him exactly where he wants him. When he tries to get Hallie Ericson (Vera Miles) to read the statute he finds out that many in the town are illiterate and he decides to setup a school. Ford is subverting the typical Western hero (and thus, an icon of masculinity) by having him be a lawyer, dishwasher, and now local schoolteacher.

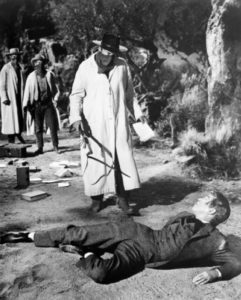

As the film progresses viewers find that Shinbone and other towns are set to vote on whether they should remain a territory or become a state. Valance  works for the cattle barons that want to keep the region a territory and threatens the safety of Shinbone should they vote for statehood. When the town votes to send Stoddard as a delegate to the state convention, Valance warns Stoddard to leave town or be killed. From there the drama turns to how a greenhorn lawyer armed with a dishrag and chalk can hope to defeat a man with a gun. Because of the flashback sequence, viewers know he wins, they just can’t imagine how.

works for the cattle barons that want to keep the region a territory and threatens the safety of Shinbone should they vote for statehood. When the town votes to send Stoddard as a delegate to the state convention, Valance warns Stoddard to leave town or be killed. From there the drama turns to how a greenhorn lawyer armed with a dishrag and chalk can hope to defeat a man with a gun. Because of the flashback sequence, viewers know he wins, they just can’t imagine how.

I don’t really want to give away anymore of the plot. I hope I’ve said enough to make you curious. It’s a classic and you don’t need me to tell you to see it. People generally don’t talk about movies 54 years after they’ve came out unless they’re good. It’s even free to stream if you have Netflix. Instead, I’d like to make two observations about the film as something to think about them when/if you watch it.

Several scholars have noted similarities between this film and Plato’s Republic. Plato talks about the tri-partite soul (reason, spiritedness, and desire) and it’s easy to see how scholars would see the connection given the three main characters and their personalities. Plato’s Republic opens with Thrasymachus arguing that Justice is the advantage of the stronger and Valance arguing that out here it’s not the law but your ability to intimidate people that gives you Justice. There are several other similarities to pick at, and if you’re a fan of Plato you can enjoy seeing the movie as validation of his central claim that Justice is each thing seeing after its business (Book IV). Many of the problems in Shinbone stem from people not doing what they should be doing or doing what they shouldn’t be doing (e.g. Doniphon should have dealt with Valance long ago and no town should ever hire a Link Appleyard to protect it). What’s essentially being examined in both the Republic and Liberty Valance is what we should do when there’s a conflict between our principles and our security/self-interest. Liberty Valance does not give a clear answer to this problem, but it does present a sophisticated story to reflect on and sharpen our intuitions about this. Given current events and political debates, as we spend this year figuring out who to govern us, it’s a topic we need help thinking through.

The other thing I want to pay attention to is the way Ford manipulates the story to deal with controversial subject matters. Contrasting Liberty Valance with The Searchers shows how far Ford goes to distance this film from reality. The Searchers open with a setting, year, and is filmed on location (even if Texas never looked quite like that). Ford avoids all of these with Liberty Valance. He gives no date and takes great pains to avoid localizing the film. The territory is always called the “state,” the state convention is held at Capital City, and even the reporter listing Stoddard’s political offices, uses wording that obscures the location. It’s also a black and white film, which is surprising given Ford’s effective use of color in prior films. Liberty Valance does not look the way it does because of budget constraints. Ford chose these elements, and I think the most reasonable assumption is that he did so to distance the film from reality in order to make a parable.

Because of this distancing Ford is able to safely deal with taboo subjects like the Civil Rights movement in the early sixties. Doniphon has a black “servant” named Pompey (Woody Strode). There are hints that Pompey is essentially still a slave. His name echoes a practice among some slaveholders to name their slaves after Greek and Roman thinkers like Scipio. Doniphon also orders Pompey around like a slave and doesn’t treat him as an equal until nearly the end. It’s reasonable to assume that Pompey chose to stay with his “Mr. Tom” after the war ended despite being nominally free. In one of the schoolroom scenes, Stoddard asks a volunteer to recite the fundamental principle of our society and Pompey stands up to recite the beginning of the Declaration of Independence. With a picture of Lincoln over his shoulder on the wall, Pompey says “We hold these truths to be self-evident,” and then starts stammering. Stoddard fills in that “all men are created equal.” Pompey says he’s sorry, that he just forgot that part, and Stoddard says, “that’s okay a lot of men do.” Doniphon enters the scene, is furious that Pompey is learning, and orders him to leave. It’s a subtle, but powerfully done critique of race relations and inequality in education that we still wrestle with to this day. Ford laces the film with several of these critiques and none of them seem preachy or out of place.

Because of this distancing Ford is able to safely deal with taboo subjects like the Civil Rights movement in the early sixties. Doniphon has a black “servant” named Pompey (Woody Strode). There are hints that Pompey is essentially still a slave. His name echoes a practice among some slaveholders to name their slaves after Greek and Roman thinkers like Scipio. Doniphon also orders Pompey around like a slave and doesn’t treat him as an equal until nearly the end. It’s reasonable to assume that Pompey chose to stay with his “Mr. Tom” after the war ended despite being nominally free. In one of the schoolroom scenes, Stoddard asks a volunteer to recite the fundamental principle of our society and Pompey stands up to recite the beginning of the Declaration of Independence. With a picture of Lincoln over his shoulder on the wall, Pompey says “We hold these truths to be self-evident,” and then starts stammering. Stoddard fills in that “all men are created equal.” Pompey says he’s sorry, that he just forgot that part, and Stoddard says, “that’s okay a lot of men do.” Doniphon enters the scene, is furious that Pompey is learning, and orders him to leave. It’s a subtle, but powerfully done critique of race relations and inequality in education that we still wrestle with to this day. Ford laces the film with several of these critiques and none of them seem preachy or out of place.

There are things this film can teach us about effective persuasion. Too often, I go straight for the argument and overlook the story that would make the same point better than I could with a syllogism. Often when dealing with cultural apologetics we talk about how story moves people differently than argumentation, and that’s true; but, it also seems like story allows us to sensitively approach issues with an audience that wouldn’t give us a hearing otherwise. Ford tackled racism, the role of women in society, immigrants, masculinity, corruption in politics, and a host of issues without offending those he tries to persuade. There’s something to be learned there.